[Fall 2019]

By Dayna McLeod

Miss Chief Eagle Testickle is the muse and alter ego of Kent Monkman, a Cree artist who confronts the violent and systemic consequences of colonialism on Indigenous peoples in North America, with attention to Canada and Quebec. He often uses Miss Chief to playfully subvert dominant discourses of this history in painting, photography, moving-image works, installation, and performance. Miss Chief’s name speaks to (mis)representations of indigeneity, gender, and sexuality and disrupts all three. Inspired by We’wha, a Zuni Two-Spirit1 Native American leader, Monkman crafted Miss Chief to “honour the tradition of Two-Spirit culture in North America by creating someone that could really represent that acceptance of gender and sexuality that was present before the European missionaries arrived and started to suppress it.”2 With a touch of Cher flare, Miss Chief guides us and stars in a counter-colonial narrative in which she performs gender and indigeneity by living her best life and staging its various incarnations.

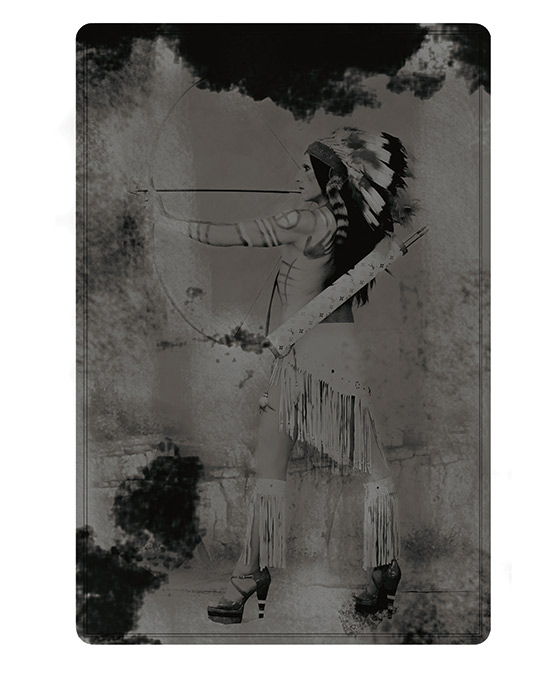

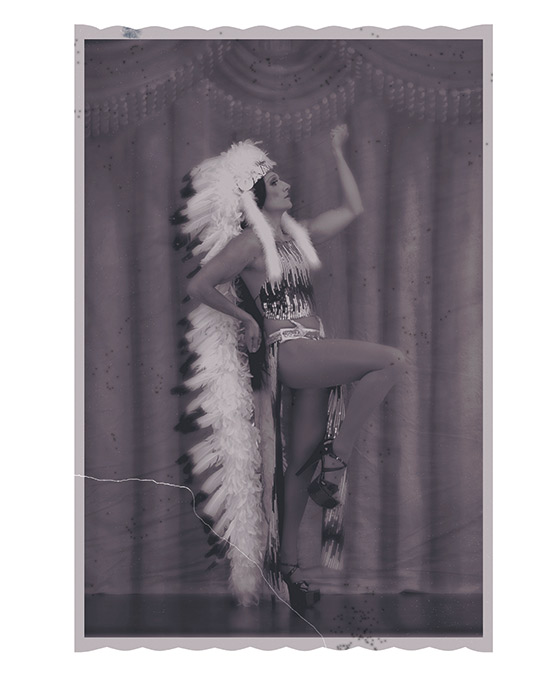

In the faux-daguerreotype photo series The Emergence of a Legend (2006), Miss Chief is figured as a performer for George Catlin’s nineteenth-century European touring art gallery, a 1920s vaudeville performer, a silent film starlet, a movie director, and a performer in Buffalo Bill’s Wild West Show. Her impersonations of these epochs, styles, and stereotypes are seamless. Here, she haunts performance and film history by inserting herself into it. She pays homage to Indigenous stage and screen stars of these eras and their original occupation of these spaces while drawing attention to how they performed amplified and exaggerated exoticism and indigeneity for white audiences under the direction of handlers such as Catlin and Buffalo Bill.

Miss Chief also figures in Monkman’s paintings that celebrate and elevate pre-contact expressions of gender and sexuality to centre Two-Spirit stories and experience. He recontextualizes painting techniques of the Old Masters to reference, impersonate, allude to, and otherwise place them in the minds of viewers so that they can clearly see his interventions in these conventions. His counter-colonial narratives firmly place Indigenous subjects as the authors of and actors in their own destinies instead of those manifested by European colonizers.

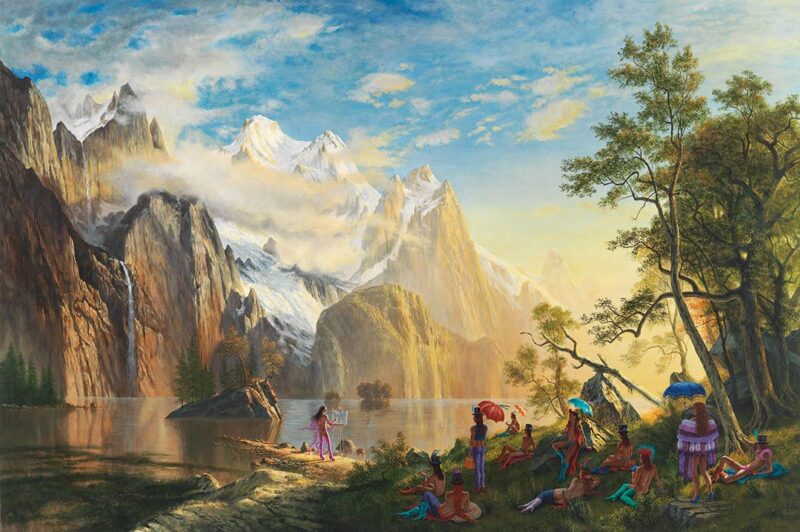

In Sunday in the Park (2010), a work that stretches six feet in height by eight feet across, we encounter the grand epicness of the painting and its subjects through scale and technique. A mountain range juts out of a lake into the sky with sunlight caressing its facing range as clouds mist its peaks and horizon. The reflection of this glorious scene is softened in water at the mountain’s base for a splayed-out crowd of dapperly dressed subjects. Miss Chief Eagle Testickle’s long, dark hair blows in the wind and hot-pink boa tendrils cascade behind her as she paints at an easel on the shore of the lake. She strikes a fierce pose in hot-pink thigh-high boots as she captures the landscape on her canvas. Miss Chief’s revellers seem to enjoy her rendering as they bask in the glory of the mountainside. This painting is reminiscent of Georges Seurat’s A Sunday Afternoon on the Island of La Grande Jatte (Un dimanche après-midi à l’île de la Grande Jatte, 1884) and stages a time when multiple genders and sexualities flourished and were celebrated among First Nation peoples, a time when masculine and feminine weren’t relegated to the binary two-sex system of opposites in Western culture. In this and other paintings, Monkman illustrates a fluidity of and playfulness with expressions and representations of gender and sexuality that overlap, dovetail, intertwine, complement, tease, and copulate. Monkman shares with us a history that has not been told in this way before.

European, American, and Canadian painters such as George Catlin, John Mix Stanley, and Paul Kane regularly painted First Nations peoples with a colonial gaze and brush. They also fancied themselves explorers. Their arrogance and superiority in this regard is still palpable. Upon encountering and documenting Indigenous peoples and painting The Dance of the Berdash (1835–37), which queer historian Hamish Copley describes as “a ceremony among the Sauk and Foxes people living on the western shore of Lake Huron” that celebrated Two-Spirit folk, George Catlin “called for the Two-Spirit tradition to ‘be extinguished before it can be more fully recorded,’”3 presumably because it didn’t adhere to his puritanical sensibilities. Monkman has used Catlin’s words as a central thesis in his work to address the insidious relationship between Christianity and colonialism and the devastation that this relationship has wreaked on Two-Spirit Peoples in North America. He also printed these words on the inside of Queen-Size Body Bag (2010), a beautiful black fringed and sequined stretched-bison-skin-shaped body bag that features a head-to-toe portrait of a glamourous Miss Eagle Testickle dressed in red on the front. This artwork is a commentary on Health Canada’s response to a 2009 outbreak of swine flu: it sent a surplus of body bags to Indigenous communities instead of providing healthcare support and preventive medicine.

Monkman further takes up the arrogant and condescending colonialist tone as exemplified in Catlin’s text to perform Miss Chief Eagle Testickle as anthropologist. She inverts colonial narratives with ease to figure European white males as her subjects for study. She dresses them up as more authentically European for a studio painting portrait in the Super-8 film The Group of Seven Inches (2005), and she describes her central role in their salvation in her performance, “The Taxonomy of the European Male”: “I have for many years contemplated the race of the white man who are now spread over these trackless forests and boundless prairies, and I have flown to their rescue, that, phoenix-like, they may rise from the stain on a painter’s palette and live forever with me on my canvas.”4

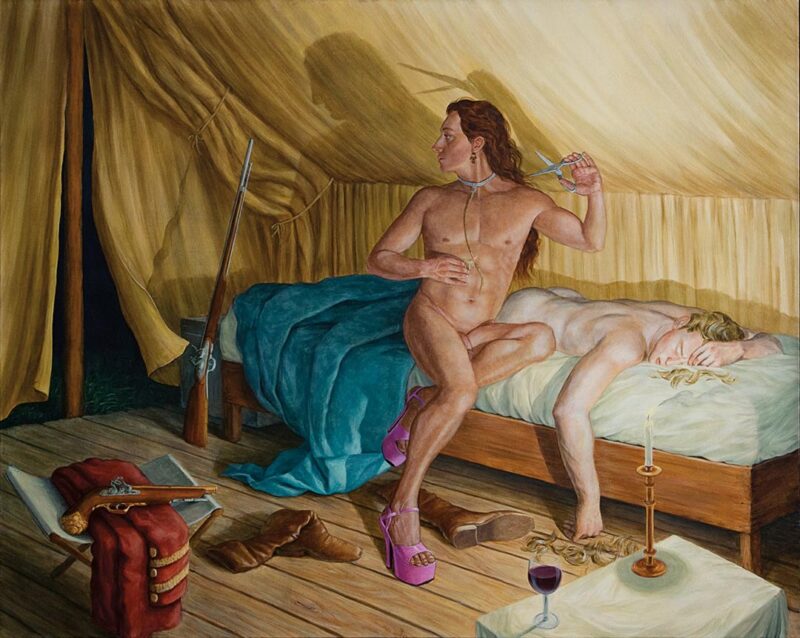

Monkman also inserts Miss Chief into seminal moments of Canadian history to disrupt, queer, and indigenize them so that we might question the authority that they hold and consider the people and narratives that they exclude. The Daddies (2016) features Miss Chief nude and pontificating in front of the Fathers of Confederation; each painting in the diptych of Wolfe’s Haircut (2011) and Montcalm’s Haircut (2011) features Miss Chief cutting the hair of her sleeping lovers as they take a post-coital doze. Her presence is felt in The Subjugation of Truth (2016) as she dons Queen Victoria drag in a portrait that hangs over a Treaty 6 meeting between a cohort of clergy, business, law enforcement, and government representatives and Chiefs Poundmaker and Big Bear, each in leg irons. Although Miss Chief is not the focus in this painting, she is embedded here as a witness to colonial cruelty and coercion. In Female Figures in a Prison (2019) and Male Figures Resisting Incarceration (2019), Miss Chief circles overhead like a Renaissance angel. These paintings mimic the epic sprawl, anguish, drama, figuration, and lighting perfected by painters such as Michelangelo, Raphael, Pontormo, and Caravaggio. Miss Chief is invoked as a beacon of hope in these harrowingly vivid depictions of incarcerated First Nations men and women, allegories of contemporary tragedy.

Other monumental paintings, such as With Our Bodies We Protect the Land (2018), Victory for the Water Protectors (2018), Washing Mary’s Tears (2018), and La Pieta (2018), also draw from the Renaissance, Mannerist, and Baroque styles. They show Indigenous activists pleading with and wincing from armed police who are dressed in full helmet-to-steel-toe riot gear complete with batons, machine guns, and pepper-spray canisters. The Scoop (2018) and The Scream (2017) show nuns, priests, and Mounties physically ripping children out of the arms of their mothers – brutality twisted onto the faces of the abductors and anguish and pain etched on the faces of the victims. Against the backdrop of Monkman’s anthology, these paintings are distinctly marked by Miss Chief’s absence, but there is no room for Miss Chief here. She cannot save, intervene in, bless, or salvage this scene.

Monkman’s prolific practice centres contemporary and historical experiences and representations of First Nations Peoples. He asks settler, immigrant, displaced, and forced-migrant audiences to consider a different version of the histories that have been fed to us in Canada since contact – a counter-history that doesn’t gloss over genocide, betrayal, and attempted annihilation of First Nations peoples by our governments, religions, and law enforcement. He asks us to imagine pre-contact life, a time before Christianity crashed onto the shores of Turtle Island and wiped out variations of gender and sexuality. He uses humour to infiltrate, and he relies on our understanding of gender as binary and our understanding of indigeneity as Other to disrupt and otherwise challenge a settler/colonial gaze. How we see Miss Chief Eagle Testickle contributes to how we see the histories and contexts that Monkman puts her in: as painter, conspirator, saviour, queen, advocate, and seductress. More than just a queering of cis-heteronormative histories and values, her interventionist work depends on an intersectional revision of colonial narratives that have figured First Nations subjects and communities as distinctly Other, whether in historical records and representations or in contemporary accounts of racism and violence. Miss Chief performs difference in order to point us to the narratives that are missing, and she challenges us not to simply see them but to acknowledge, take responsibility, and act.

2 Kent Monkman, “Monkman Lecture Transcription,” Agnes Etherington Art Centre at Queen’s, 6 Feb.2018, agnes.queensu.ca/wp-content/uploads/2014/08/Monkman-Lecture-Transcription.pdf.

3 Hamish Copely, “The Disappearance of the Two-Spirit Traditions in Canada,” The Drummer’s Revenge, 11 Aug. 2009, https://thedrummersrevenge.wordpress.com/2009/08/11/the-disappearance-of-the-two-spirit-traditions-in-canada/.

4 Kent Monkman, “The Taxonomy of the European Male,” in Two-Spirit Acts: Queer Indigenous Performances, ed. Jean O’Hara (Toronto: Playwrights Canada Press, 2013).

Dayna McLeod is a middle-ageing queer video and performance artist. She is a settler Canadian who has lived in Tiohtiá:ke/ Montréal/Montreal for the past twenty-plus years. She recently completed a PhD in humanities at the Centre for Interdisciplinary Studies in Society and Culture at Concordia University. Her artistic and theoretical research focuses on media representations of sexuality, queer identity, and how bodies marked female are often perceived as public property. See her work at daynarama.com

Kent Monkman, born in Canada in 1965, is a Cree artist who is widely known for his provocative interventions in Western European and American art history. His paintings and installations have been exhibited at numerous institutions in Canada, the United States, and Europe. Monkman’s second nationally touring solo exhibition, Shame and Prejudice: A Story of Resilience, who will visit nine museums across Canada until 2020, was shown at the McCord Museum, in Montreal from February 8 to May 5, 2019. Kent Monkman is represented by Pierre-François Ouellette art contemporain in Montreal. kentmonkman.com

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 112 – COLLECTIONS REVISITED ]

[ Individual article in digital version available here: Kent Monkman, Miss Chief Eagle Testickle — Dayna McLeod, Disrupting Colonial Comforts and Settler Sensibilities ]/span>