[Fall 2019]

By Stephen Horne

The Map and The Territory is a large and intricate exhibition of colour photographs by the late Italian artist Luigi Ghirri at the Jeu de Paume in Paris.1 No doubt the curator of the exhibition, James Lingwood, adopted this title following up on a note that Ghirri wrote in 1970 in which he explained that “his aim was not to make photographs, but rather charts and maps.”2

An early image, Modena (1970), could be a fragment from arte povera, and this suggests we might gain insight into Ghirri’s life and work by asking after the spirit of arte povera, the most important artistic current of the epoch in Italy. When he turned to photography, Ghirri abandoned his profession as a land surveyor, but his direction in photography suggests that he had not entirely forgotten the procedures of that profession, which is also a kind of framing activity related to the work of architecture. It might also be interesting to connect Ghirri’s story with the work of the American architectural theorist Kenneth Frampton, whose theory of dwelling in the local could be pertinent in relation to exploring, and perhaps expanding, the relevance of Ghirri’s practice.

“I have always worked on any (initial) project, not conforming to a rigid scheme, but remaining open to intuition and the chance occurrences I encounter over the course of the work.” These words by Ghirri partially describe his photographic practice and what distinguishes it from that of other photographers whom we might see in institutional galleries and museums, even though the subjects could be similar…<!–For example, both Ghirri and Hiroshi Sugimoto have photographed dioramas in natural history museums, and both Ghirri and Stephen Shore have frequently photographed billboards, urban clutter, and such. Examination of a few photographs by Ghirri reveals fundamental differences, both practical and ideological, but also of interest is his commitment to writing on photographic themes and the work of other artists, an eclectic range from Jacques Henri Lartigue to Bob Dylan, but he has written that Walker Evans was the artist he felt closest to. In his writings it is always evident that what motivated him was his personal need to take responsibility not for his own activity but for photography itself. In this matter, his contribution sets him apart from the momentum of the art world prevailing in his time. While the conceptualists were busy optimizing art for greater power output, Ghirri followed the wandering and paradoxical course of cosmopolitan marginality. He mentions having been affected primarily by American photographers such as Robert Adams, but Lewis Balz might be a closer fit. Balz seemed to feel the same sense of responsibility for photography as did Ghirri and, like Ghirri, expressed this through extremely insightful and well-informed writings on issues of the day and the work of other artists.

This aspect of responsibility and generosity is one of the things that set Ghirri apart; it is the ethic that he proposed with his model for practice. His approach was characterized by affection and even compassion – not simply for his subjects but for the activity with which he engaged. Most fundamental was the relationship that he established among his walks, the act of photographing, and the writing that he commenced from the outset of his photography practice. The nature of his walks, whether in his personal surroundings or further afield, was that of a wandering stroll through an ordinary neighbourhood. Often, though not always, he walked in his hometown of Modena, Italy. Keeping a sense of locale and of simplicity was a kind of discipline for him. He used a camera, film, and laboratory that he described as “normal.” The technical quality of his prints was perhaps “good amateur,” and his prints were always domestically sized, often as small as five by seven inches, but never monumental or grandiose, and perhaps this was his avoidance of a professionalized expertise, as he preferred to “be alongside others,” as he put it. What was also remarkable was his use of Kodachrome colour film, which distinguished his work from that of his “more serious” peers of the time who worked only with black and white. The choice to use colour renders his prints approachable – one might want to say “amateur,” but then one hesitates, as intense selectivity and formal discipline have been exercised in each image; all have a considerable decisive weight. Every one is presented in the terms of aesthetic experience.

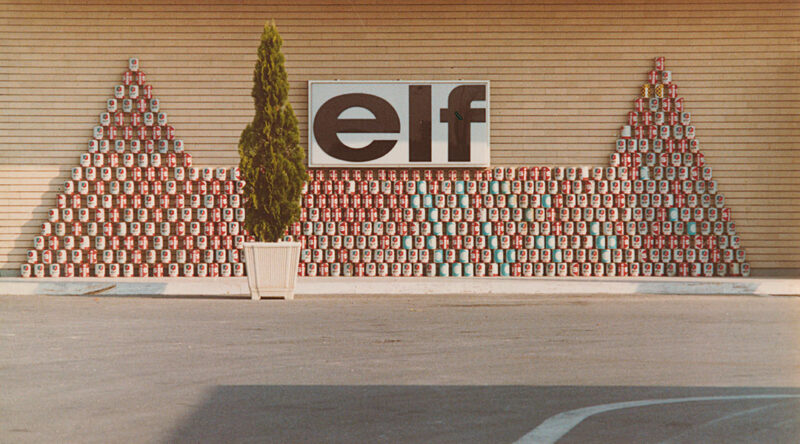

Many of Ghirri’s images, being of billboards, street posters, commercial promotions, and occasional informal messages, were gathered by this “method.” For example, Roma (1978) is simply a crumpled and folded newspaper lying on the paving stones of a street. The left-hand column is occupied by a headline quoting a phrase (“HOW TO THINK THROUGH IMAGES”) by seventeenth-century cosmologist Giordano Bruno, who argued for an infinite universe without centre. Bruno was an inspiration for Ghirri, and his notions appear frequently in Ghirri’s own essays on art.

A discarded wrapping paper from a panettone box, monochrome wrinkled shiny blue and star covered – this was a “find” of the absolute opposite to the Duchampian version of the rendez-vous. The panettone wrapper bears a message of light from the stars to a photographer who could feel what he was seeing. We still sense how this crumpled crinkly paper, even in its documented form, seems able to give off the sound of being handled, touched, and discarded.

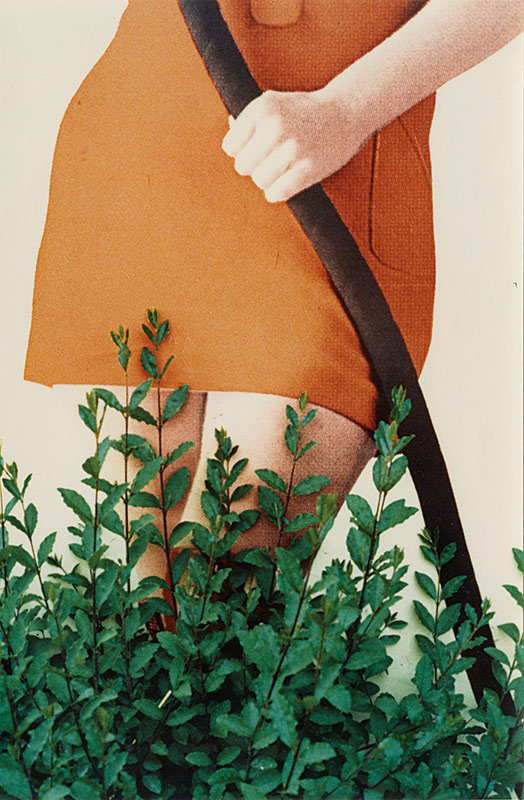

It may seem unusual to evoke the experience of touch in relation to photography, but the term seems pertinent to a discussion of this exhibition. In this case, though, what I mean by “touch” is somewhat figurative, as in “light touch,” and this may work to continue the reference to the photograph as something existing on the basis of being touched by light. In a short essay accompanying the series Colazione sull’erba (1974), Ghirri wrote that he “sought to offer an existential portrait, as well as a series of references to the natural world, to home, and its contemporary inhabitants.”3

There is also a strong reference to the notion of an aesthetic present that Ghirri proposed through this “light touch.” Delicacy, exactitude, and simplicity are aspects of most of his photographs. They are “of the moment,” although certainly not in the sense of the heroic “decisive instant.” They have the feeling of being superbly balanced between being just “any old thing” and something exquisite. The subjects of his images no doubt often belong in the category of “the overlooked” that is so important to artists in general. But finally what strikes us most is the thought that Ghirri’s work proceeds by way of affection, a perfectly simple thing, affection for the everyday human environment and his recognition that he could reveal this to others and that through this something larger was being made.

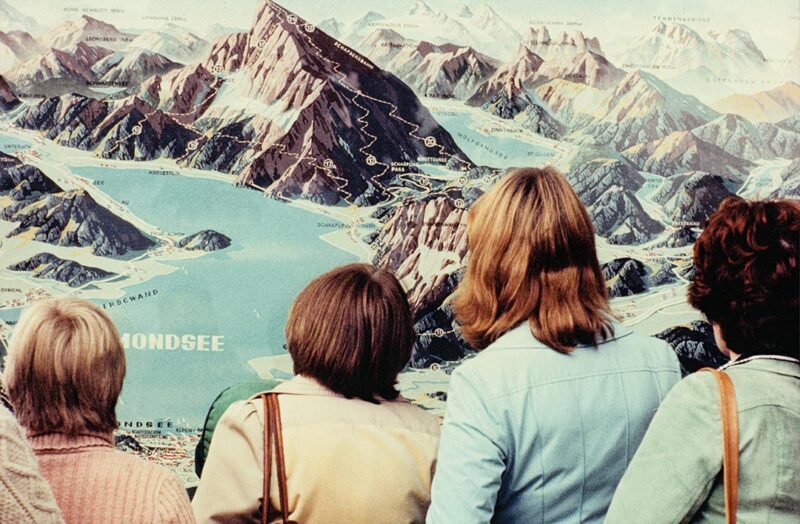

Ghirri’s images seem to gather their visibility from our seeing a kind of animation, of motion or movement, within stasis. In fact, his images assemble not themselves but our seeing, the actions and behaviour of seeing. These photographs show us the event of some kind of “thereness” that exists in the animated moment; they have a life that is what is meant by the concept of animism, a seeing that in this work is close to cinematic, the cinema of an unfolding vision, planes and surfaces, volumes, borders, and boundaries all interacting in our regard.

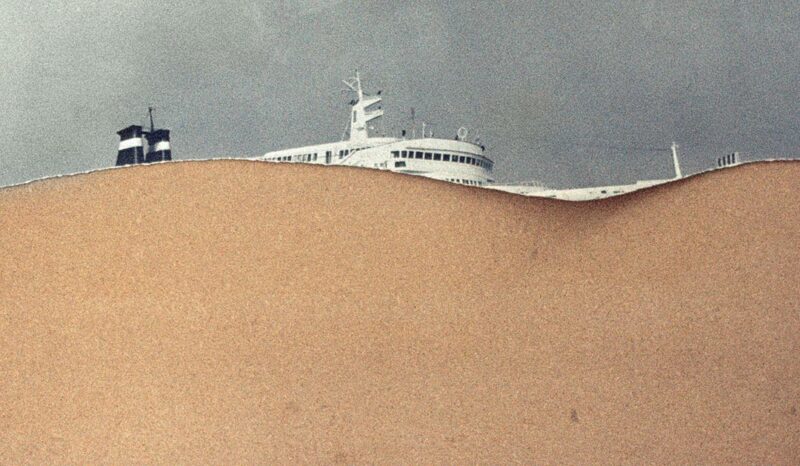

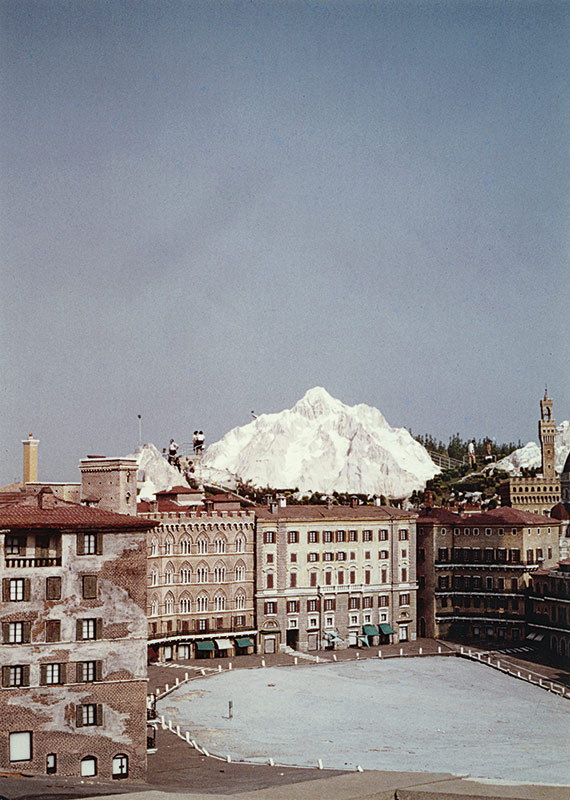

These images function on the model of a mesh or a screen. In their attention to the folding and unfolding that is the visible, we learn something of what is contained in the concept of the photograph as a medium. Ghirri’s photographs document the warp and weft that is the visible, what Merleau-Ponty so eloquently called “the fabric of the world,” and this might be the source of their mysterious intimacy. In these images there is folding and unfolding, like that of a flower going through its daily cycles in response to changes of light and temperature. This movement takes place along lines where Ghirri identified discrepancies between differing kinds of space as already represented in “found” photographs then combined into images such as Bastia (1976), in which the upper structure of a large ship appears to be sailing past a wall that is obscuring its lower part. The fragmented ship image and the literal space of the wall make for a contested space, a space that Ghirri contended was being colonized by another, the space of media. Although Ghirri was involved with creating images, he hoped by this route to contribute resistance to what he felt was an invasion of living environments by images and, with this, the destruction of direct experience. The everyday presented in a photograph becomes the formerly everyday due to the variables of framing, isolation, and fragmentation and the reconfiguration of stasis and motion. What we see in Ghirri’s photographs is his documentation of the transformation that takes place between a photograph and its subject. So much of this is a matter of the photographer’s composition in the broad sense of the word, and this is where Ghirri has consistently placed his emphasis through his “simple” frontal isolation of a subject and letting the deletion of the environing space play its role.

Ghirri’s importance lies in his assertion of a local surrounding within the realities of a globalized and media-driven environment, as well as his maintenance of human life in a future in which the threat of human extinction is now being discussed. In a time when so much authority is given to expertise and technically engineered solutions, an artist such as Ghirri functions to propose that alternatives exist. As Bono recently said, “Intimacy is the new punk.”

2 Luigi Ghirri, The Complete Essays 1973-1991, trans. Ben Bazalgette and Marguerite Shore (London: MACK, 2017), 22.

3 Ibid., 27.

Stephen Horne is an independent curator and writer living in Montreal and France. He has taught at NSCAD and Concordia University, and his work has been published in periodicals, catalogues, and anthologies in Canada and elsewhere.

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 113 – TRANS-IDENTITIES ]

[ Individual article in digital version available here: Luigi Ghirri. Flatness and Its Frame — Stephen Horne ]