[Winter 2020]

Ryerson Image Centre, Guest curator: Sandrine Colard

September 11–December 8, 2019

By Jill Glessing

Photography extends the gaze, making material its spectrum of desires and subject positions – whether violence, control, submission, negotiation, or resistance. Once etched as image – on plate, print, or screen – the momentary exchange circulates and is entrenched as truth. For The Way She Looks, curator Sandrine Colard expands John Berger’s assessment of patriarchal visual dynamics – “Men look, women are looked at” – into realms of racial power. And then, she undoes it. Through over one hundred works drawn from the Walther Collection, of and by African women from the mid-nineteenth century to the present, Colard prompts viewers to consider alternate ways of reading images.

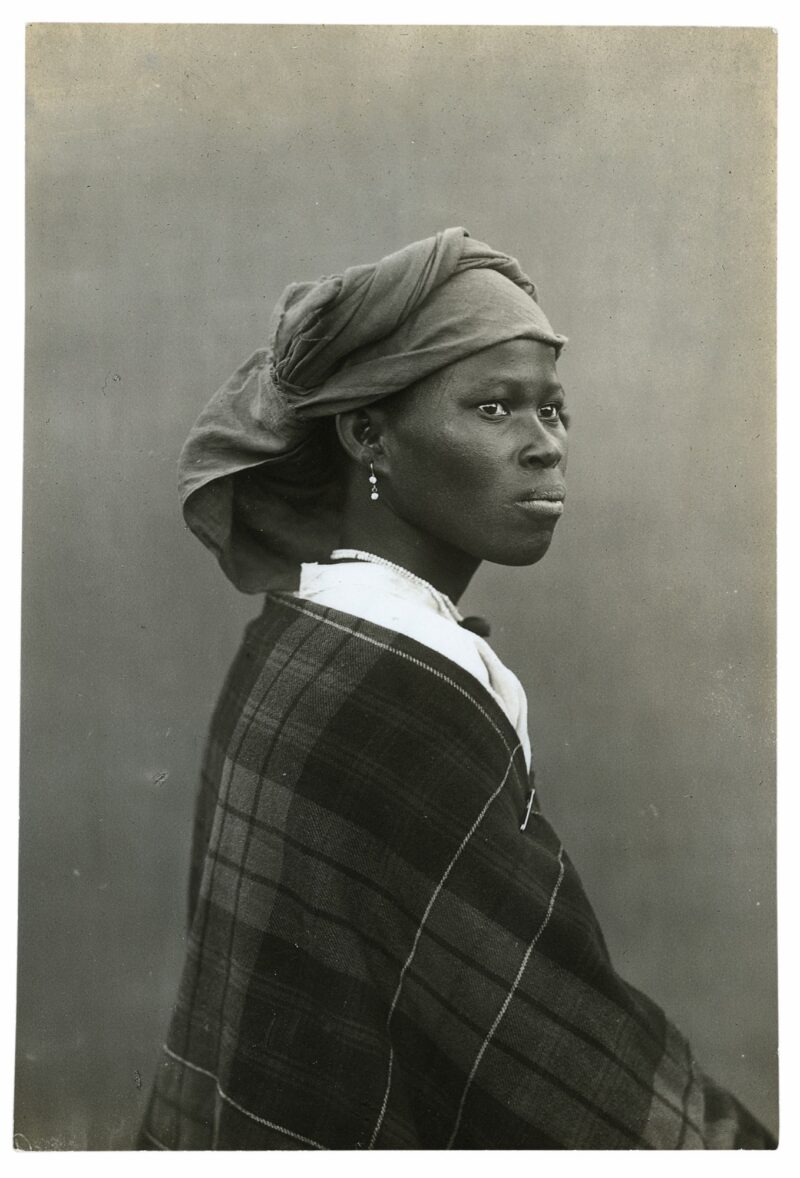

The photographic encounter as performed for ethnographic archives, objectifying its subjects, is critiqued. The exhibition begins with a wide range of such images made to illustrate typological specimens for burgeoning fields of colonial ethnography and to support racial hierarchies. African women were staged performing traditions such as hairdressing, nude, and carrying babies on their backs. Postcards, cartes de visites, and albums, produced as exotica and erotica, were distributed through European markets. Indigenous women were also photographed in European-style portrait studios using Western conventions of fashion, pose, lighting, and painted backgrounds to create sensitive character portraits suggesting Eurocentric respectability.

The anonymity of production of many of these images blocks our knowledge about transactions between the mostly white, male photographers and their subjects. The absence is useful for Colard, as it opens space for alternative interpretive strategies. Following Tina Campt’s work of “listening to photographs,” it is proposed that “frequencies” or “muscular tensions” in facial expressions may reveal sitters’ experiences – whether resistant or willing. This subversive hermeneutics allows for a more fluid visual economy that challenges “truths” embedded in rigid ethnographic formats and can recuperate subjects’ agency. Colard claims that at times, “the female sitters’ confident and forthright gazes rival that of the photographer.” The concept collides provocatively with what is now the more established understanding of the medium: its inability to reveal truth.

The strategy becomes increasingly unnecessary as the exhibition jumps chronologically into the mid-twentieth century, when more production details are known and fomenting independence and women’s movements were beginning to unravel power imbalances inside and outside the frame. A selection of prints by each of the Malian Bamako commercial studio photographers, Malick Sidibé and Seydou Keita, show their female subjects – paying customers commissioning portraits for their own use – as self-fashioned performers in their chosen outfits and poses. Some adopt Western styles, reflecting perhaps the threat to African cultural sovereignty that Steve Biko termed “mental colonization.” But other subjects proudly display elements seen in nineteenth-century images – textile patterns, surface design, hair dressing, and social adhesion – indicating the strength of their traditions. One example is Keita’s portrait of two women, wearing identical fabric designs signifying kinship and solidarity, standing before patterned backgrounds. This haptic surfeit of surface rippling across flattened pictorial space is favoured over the Western pictorial convention of realist perspective.

Enduring cultural traditions are similarly demonstrated in J.D. ‘Okhai Ojeikere’s project, Hairstyles. In the 1950s during Nigeria’s independence movement, Ojeikere began travelling through his country to document women’s regional hair designs – a subject that also fascinated colonial photographers. He made over two thousand negatives to celebrate and promote African culture, four of which are presented here. Their square format, careful lighting, and fine printing situate them as fine art prints, but their strict adherence to the back or profile view associates them with both the colonial classificatory style and the modernist Neue Sachlichkeit. This curious amalgam of Western genres is corralled for the struggle for national sovereignty.

Cameroonian portrait photographer Samuel Fosso promoted African culture through his series African Spirits (2008). Fosso donned elaborate costumes to represent important cultural figures from Africa and its diaspora. His impeccable impersonation of Black nationalist Angela Davis, haloed by her magnificent afro, is a remarkable exploration of Black gendered identity.

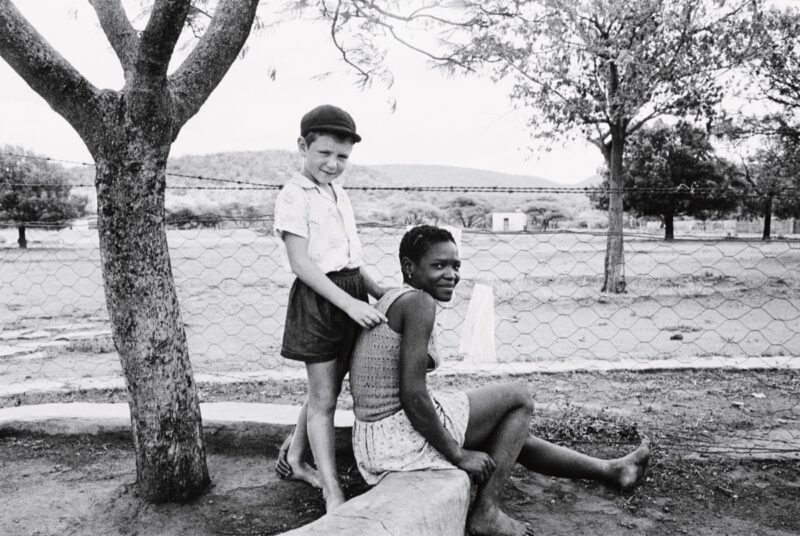

In support of South Africa’s anti-apartheid movement in the 1980s, photographers David Goldblatt, Guy Tillim, and Santu Mofokeng captured racial conflict in the international black-and-white social documentary style of the period. Photojournalism organizations such as Afrapix and the educational Market Photo Workshop were and, in the latter case, remain important in nurturing young Black photographers. Goldblatt’s A farmer’s son with his nursemaid, Heimweeberg, Nietverdiend (1964) shows a tender exchange between his subjects in front of a barbed-wire fence that poignantly illustrates the pain of apartheid division.

Women step out of the frame in the exhibition’s final sections. In two street portraits from Nontsikelelo “Lolo” Veleko’s series Beauty is in the Eye of the Beholder (2003), in a style not dissimilar to ethnographic portraits, young women proudly display their colourful hybrid flair. The now-familiar African interest in pattern and textiles is employed in four videos from Grace Ndiritu’s series Still Life (2005–07) to disrupt the Western bodies, as seen extensively in the exhibition’s historical images. In each video, a woman shifts and slides between expanses of patterned fabrics, revealing only glimpses of her naked body. This playful melding of references – Henri Matisse’s flat coloured canvases, the nude models upon whose bodies modernist abstraction was developed, and Western perspective.

The gender posturing seen in Fossi’s work becomes full blown in other artists’ works. South African “visual activist” Zanele Muholi dedicates her practice to celebrating and supporting LGBTI South Africans through portraiture. Although the post-apartheid Constitution enshrines their rights, marginalization and violent targeting continue. Muholi’s committed purpose does not detract from the aesthetic value of her often beautiful large colour prints. Like the earlier ethnographic images and Ojeikere’s Hairstyles, this project might also be considered typological. The five portraits from her series Faces and Phases (2006–ongoing) stage transgendered individuals. Muholi updates the tired old, pain-laden anthropological formats: the tall Black transgendered Miss D’vine I (2007), her flat chest bereft of the breasts so compelling for Western ethnographers, wears a plastic beaded Zulu skirt and red stilettos and sits centred against road-side grasses littered with plastic detritus.

The exhibition’s celebratory dénouement is a large colour portrait that takes over the final wall – South African Jodi Bieber’s Babalwa (2008) from her series Real Beauty. A formidably large Black woman wearing only white undergarments, heels, and jewellery, her body an undulating s-shape of fleshy folds, stares down the camera’s, and our, gaze. Women, now as both photographer and subject, have arrived and are standing their ground.

Jill Glessing teaches at Ryerson University and writes on visual arts and culture.