[Summer 2020]

By Claudia Polledri

The third edition of the Biennial of Contemporary Arab World Photography,1 curated by Gabriel Bauret, was held in Paris in 2019. Inaugurated in 2015 on the joint initiative of the Arab World Institute (AWI) and the Maison européenne de la photographie (MEP), the event is important because it showcases works that are often difficult to access and are not often seen in international events. The AWI and the MEP presented the biennale’s main exhibitions: the retrospective devoted to Anglo-Moroccan artist Hassan Hajjaj (MEP) and Liban Réalités et fictions (Lebanon – Realities and Fictions), organized by Bauret and Hanna Boghanim (AWI). Additionally, La Cité internationale des arts hosted, unfortunately for too short a time,2 the group exhibition Hakawi/Récits d’une Égypte contemporaine, curatedby Diane Augier and Bruno Boudjelal, and the Mairie du 4e arrondissement opened its galleries to an exhibition by Franco-Algerian photographer Lynn S.K., Aller, Retour. This core group of exhibitions was supplemented by shows at five galleries.3

Despite the breadth of the art on offer, the event could not be expected to provide an exhaustive cartography of contemporary creation from this area of the world – a perhaps too-ambitious intention. The series of exhibitions brought together a multiplicity of gazes, in which works by photographers who live in the region and in the diaspora were accompanied by those produced by photographers from other places who found the visual context for their projects in the geographic space of the Arab world. The result was a very mixed grouping that included both engaged works closely related to political and social realities and others based more on aesthetic research. To this variety of approaches was added the reference to a region that is vast, complex, and far from homogeneous, despite the idea that might be conveyed by the standardized and efficient label “Arab world.” It was thus by focusing on the photographs, measuring their connection with reality and the angle chosen to represent it, that spectators could unearth the intricacies of the cultural and geographic space brought to bear and take account of the different gazes on the “Arab world.”.

Lebanon: Between Reality and Fiction. Presented at the AWI was the two-part exhibition Liban réalités & fictions. The first part presented artists who captured reality and the main issues in contemporary Lebanon; the artists in the second part adopted a fictional and dreamlike approach. But despite this distinction, photography, as always, blurred the maps and challenged the frontiers of representation.

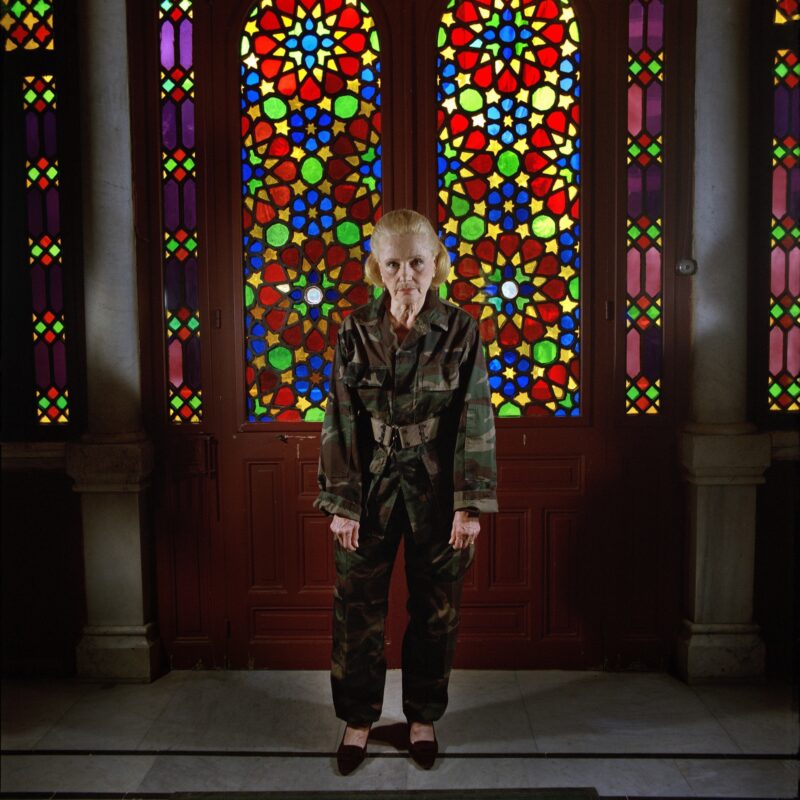

The exhibition path began with the brutal reality of the Lebanese civil conflict (1975–90) evoked by the Beirut photographic mission4 organized, at the end of the war, by the clairvoyant Dominique Eddé. To document the city and the photographers who recorded it during the mission, the curators chose a little-known short film by Tanino Musso5 that offered significant evidence of the link between the contemporary history of Lebanon and photography. The series by Dalia Khamissy (The Missing of Lebanon, 2010) and Lamia Maria Abillama (Clashing Realities, 2006) showed how palpable the traces of the war remain in civil society. They could be seen in the petrified faces of women watching over portraits of the dead (brothers, husbands, children) and in the combat uniforms in which Abillama dressed the women she photographed – a tangible sign of the past persisting in the present. And then, of course, there was the territory, the real and remembered landscapes in which recollections of the conflict overlap and emerge either with documentary features (Nadim Asfar, La Montagne, 2014) or with reconstructed, yet oh so real, ones (Zad Moultaka, land escape6).

In Omar Imam’s series Live, Love, Refugee (2015), refugees from the Syrian conflict took centre stage. The surrealist approach chosen to portray them mixed reality and fiction, as in the Fellini-esque shot of a blind woman sitting beside a tent and listening to her husband, disguised as a street hawker, recounting her favourite TV shows. As if in a reversed mirror, François Sargologo’s Beyrouth Empire (2018) immersed spectators in a similar circus-like atmosphere. In this case, the main reference to the world of the storyteller (hakawati) and boxes of wonders (sunduq al-Aja’ib7) couldn’t keep reality from resurfacing via family photographs or monuments ensconced in a dream-like setting. Photographic contradictions.

Another Lebanese topos, Beirut nights, was displayed in the impertinent photographs by the young and talented Myriam Boulos (Nightshift, 2015) that testified to the desire for freedom of a generation of young women sometimes still confined by a patriarchal framework. Women – bodies abandoned on the ground in the corner of the image – were also on view in Lara Tabet’s series Underbelly (2017). By offering a reinterpretation of a classic photographic subject, the crime scene, these pictures gave further evidence of how porous the border – and not just the photographic one – is between reality and fictions.

Among the other exhibition themes, in addition to the reference to exile offered by Maria Kassab, Gilbert Hage’s touching pictures devoted to the Armenian community, and Tanya Traboulsi’s series taken between Lebanon and Austria, were, of course, a number of portrayals of Beirut, real and imaginary, sprinkled with incongruous structures. Vicky Mokbel’s study of the abandoned EDL building (EDL: On-Off/In-Out, 2015) was no doubt the most meaningful of these, signifying in just a few images the state of an entire country affected both by power outages and by the inertia of its political class. In fact, it is precisely against this inertia that Lebanese society has been protesting since last October,8 giving rise to one of the largest mobilizations in recent years. The young generations on the front lines hope to be able to imagine their future and the reality of their country in a different way.

Egyptian Narratives. The exhibition Hakawi – Récits d’une Égypte contemporaine was born of the “desire to tell about today’s Egypt.” It did this through seventeen projects produced by young creators living and working in the country, whose projects were chosen following a significant search in the field.9 Through a documentary approach, the photographers recounted, touchingly and realistically, some of the current issues in Egyptian society and offered different images of certain strata of society beyond the stereotypes.

Problematic at both the local and global levels, the environmental crisis and pollution were the subject of Ahmed Gaber’s Delta (2016–19) and Mohamed Mahdy’s Moondust (2016–18). Focused, respectively, on rural zones in the Beheira governate, west of the Nile delta, and the residential Wadi El Qamar neighbourhood, west of Alexandria, these two photographic essays portrayed the consequences of drought on agriculture and the effects of the Portland cement plant on inhabitants’ health. In both cases, the dust-covered faces and furniture evoked the same feeling of powerlessness and waiting for an unlikely change – aggravated, in Mahdy’s series, by the indelible traces on the inhabitants’ bodies.

Bodies and the body were also the subject of Eman Helal’s striking pictures (Just Stop, 2011–16) dealing with sexual harassment and violence against women, and of Heba Khamis’s series Transit Bodies (2019), through which she reported on the discrimination suffered by transgender people – in spite of the fact that gender reassignment is acknowledged by Islam. The intense but never voyeuristic gaze that Helal and Khamis cast on these intimate and collective issues aimed to deliver their subjects from the social judgment under which they suffer by offering them new dignity through the images.

Among the other themes addressed were the questions of an entire generation with regard to what remains – or, rather, what was lost – after the 2011 revolution – that is, explains Ebrahim El Moly (Once upon a time, 2019), “loved ones, dreams, and hopes.” Symbolized by gazes that are lethargic, subdued, and confined to the space of the house due to the inertia imposed by the social and economic context, the portrayal of these losses was accentuated by images of barricades, erected when the hope for change was still alive. Here, the temptation to flee “from the lost hopes and dreams, the scars and hidden wounds” is no doubt strong. It was evoked by one of the most poetic series in the exhibition, Hana Gamal’s We’re All Fugitives (2016–19), in which, through a play on framing and mirrors, she turned the camera into a tool for introspection.

The daily life of Egyptians was certainly the other protagonist in these photographic narratives. It emerged playfully in the light-hearted portraits of families at the beach in Roger Anis’s essentially traditional sociological study (Shaabi Beaches, 2017–18) and in Fatma Fahmy’s nocturnal pictures (Waltz with the Tram, 2019) in which she explored the liminal zone between day and night, when people coming home after a long night of work cross paths with those beginning a new day. And they also hope for a better future.

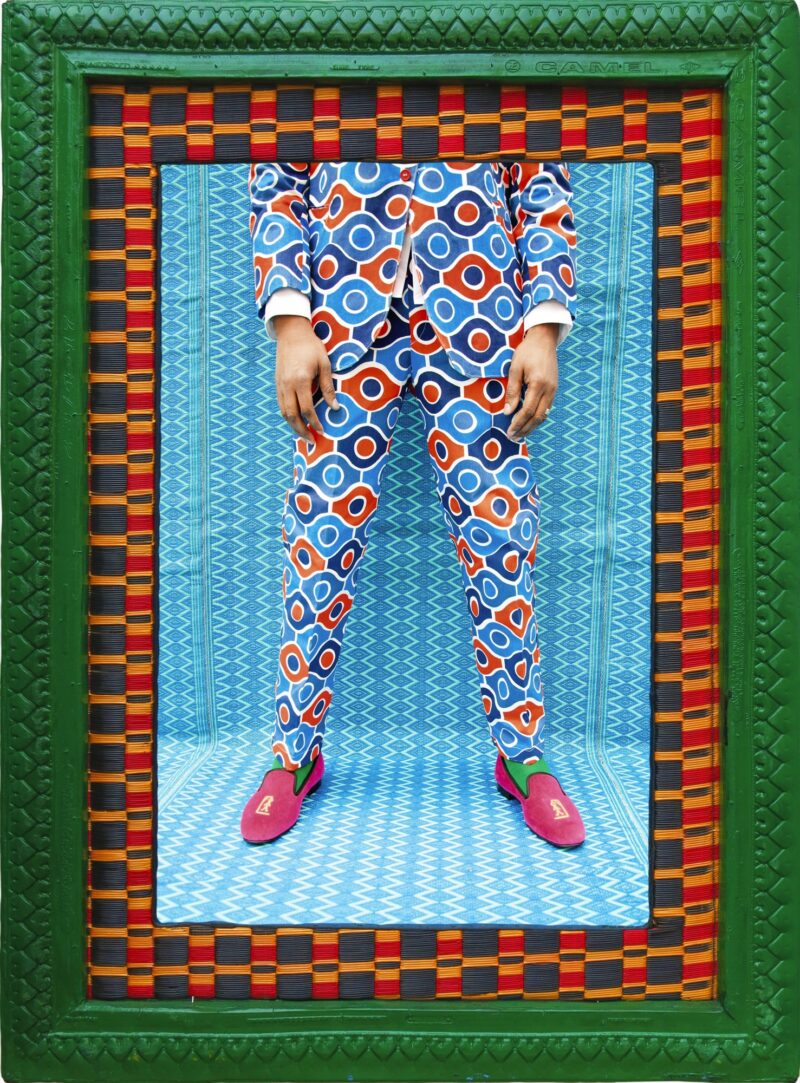

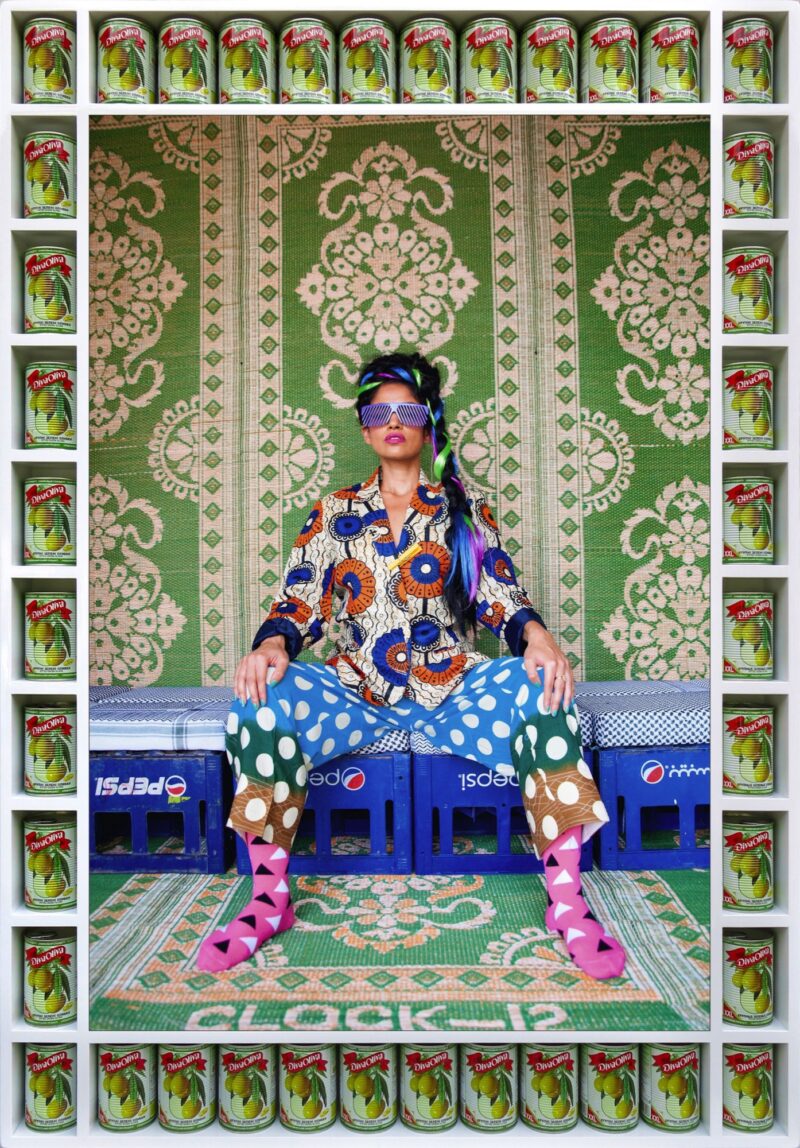

Morocco Pop. The Maison européenne de la photographie (MEP), the second main host of the biennale, chose to give carte blanche to English-Moroccan artist Hassan Hajjaj (born 1961), who lives and works in the United Kingdom and Morocco. For the occasion, he appropriated the site, transforming it into “La Maison marocaine de la photo.” This was not an empty gesture, for the furniture and decorative elements in the space were almost as important as the images, and they guided spectators on an enchanting and psychedelic journey through an explosion of colours and fabrics enveloping bodies and faces. The exhibition was composed essentially of large-format portraits of men and women, alone and in groups, whose choreographed – even acrobatic – poses accentuated a sense of lightness.

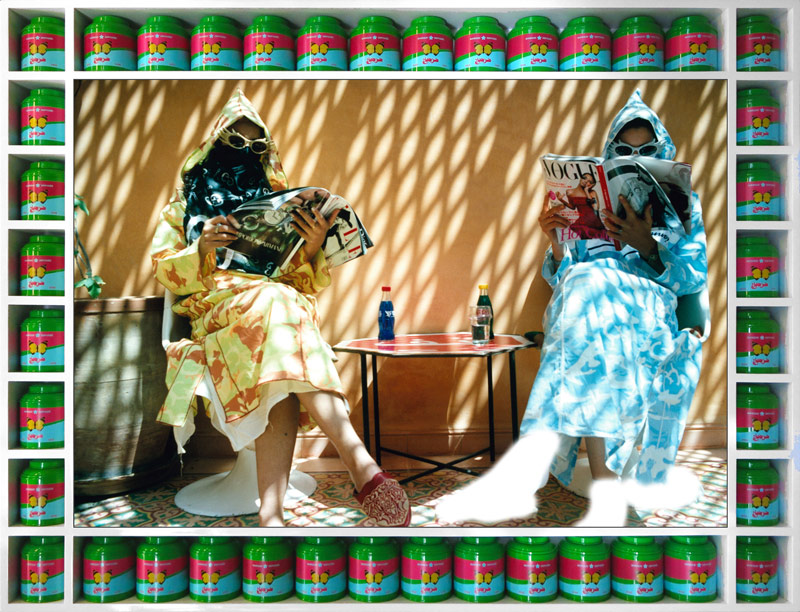

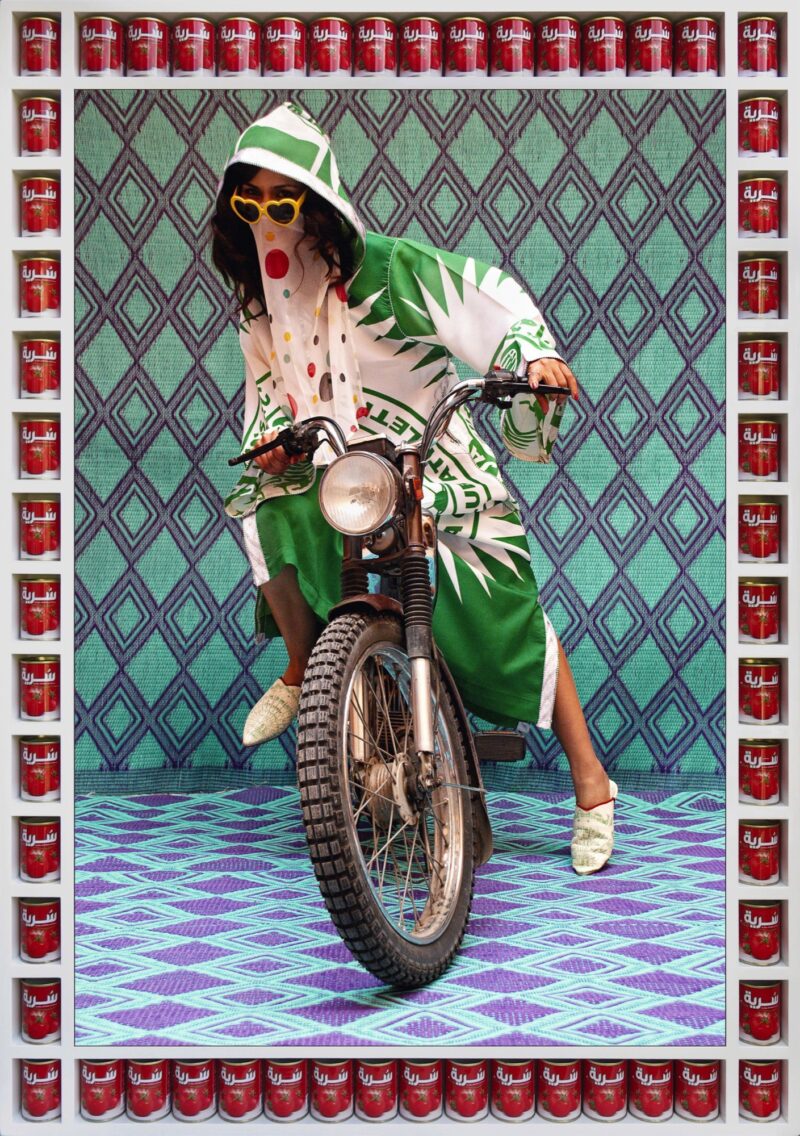

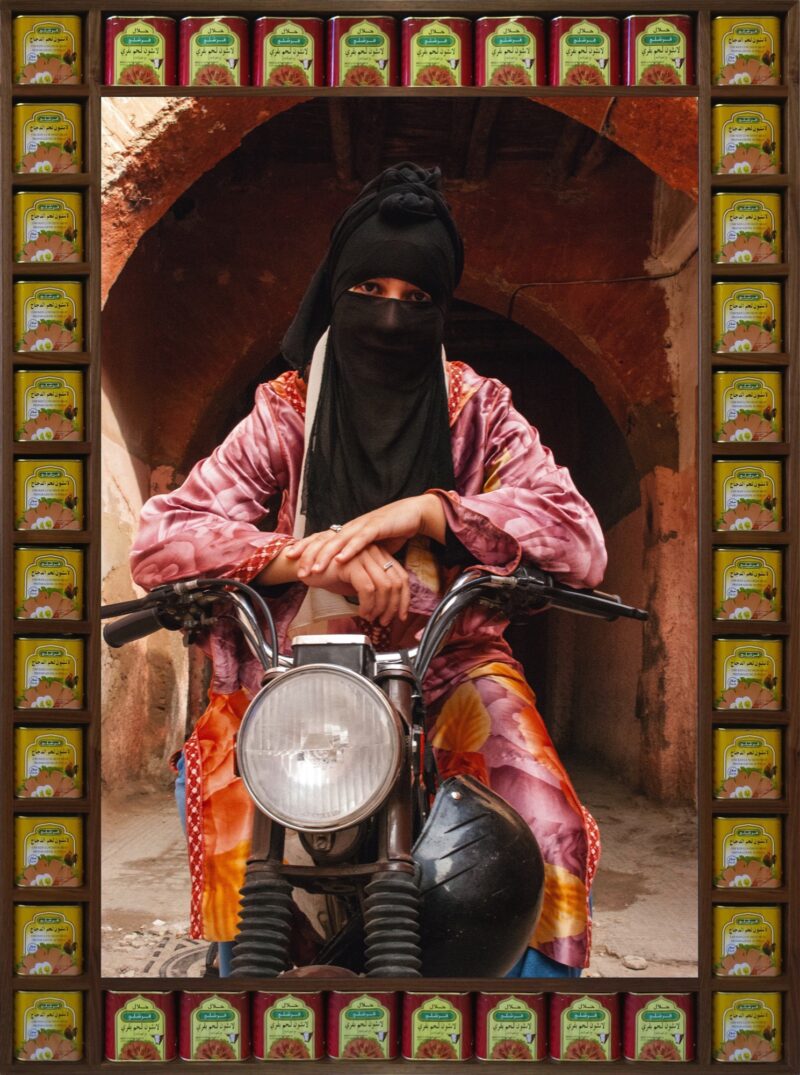

Colour was no doubt the true protagonist of this series. It saturated garments, background images, and settings, offering dreamy alchemies between floral motifs and stripes. Hajjaj, an extraordinary colourist, also used hues to accentuate the effect of depth in the images. This original idea was, if possible, strengthened by the works’ frames. By enhancing them with jam jars or wallpaper, Hajjaj aimed to remove them from their support function and place them in dialogue, by association or by juxtaposition, with the images. It was, of course, the sparkling colours of Morocco that were combined in a range of pop tones that Hajjaj drew from his association with the world of fashion. The references to this world were obvious, evoking, surrealistically, the contrasts in a society caught between tradition and modernity. Scarves, hijabs, and djellabas were complemented by leopard-skin patterns and sunglasses, the logos of famous designers well in view.

The first exhibition space was, in fact, devoted to this world (Vogue: The Arab Issue). The second space, with the same visual grammar, featured two series, Gnawi Riders (Gnawi women musicians) and Kesh Angels (women riding their motorcycles). In the third space was the series My Rockstars, devoted to figures from entertainment, fashion, and music, including Rachid Taha and Hindi Zahrapour, with whom Hajjaj has had professional collaboration. After so much colour, which, despite the originality of the project, was on the verge of becoming monotonous (due to its excess), spectators’ eyes finally found relief when they arrived at the final series, composed of new black-and-white photographs, whose chromatic uniformity nevertheless didn’t conceal the subjects’ joviality and the beauty of their smiles.

These diverse visual itineraries effectively represented the heterogeneous, complex space covered by the label “Arab world” – a label within which artists from cultural minorities who do not identify with national references also struggle to fit. It is to be hoped that the biennale will continue on this courageous and necessary mission to highlight this cultural production, perhaps by accepting the challenge of bringing together exhibitions under a common theme. It is a major task, no doubt, but it would enable the event as a whole to gain greater cohesion without erasing the differences that describe the complexity and richness of the region. Translated by Käthe Roth

2 The exhibition took place September 11–28, 2019.

3 Galerie Agathe Gaillard, Galerie Clémentine de la Féronnière, Graine de photographe, Galerie XII, and Galerie Basia Embiricos.

Claudia Polledri is a postdoctoral researcher in the Department of Art History and Film Studies at the Université de Montréal, where she earned a doctorate in comparative literature devoted to photographic representations of Beirut (1982–2011). An expert in Middle Eastern contemporary photography, she was curator of the exhibition Iran. Poésies visuelles, presented in Quebec in 2019.