[Summer 2020]

[Technology] is no longer opposed to human beings but is being integrated with them and gradually absorbing them.

— Jacques Ellul

By Alexis Desgagnés

I was asked to write about Benoit Aquin’s La dimension éthérique du réseau par Anton Bequii.1 It’s not the first time that I’ve been asked. I haven’t said yes until now, for reasons that I mention with a concern for honesty in case anyone thinks that this will be an analysis by an accredited art historian. As an author, I often feel that my writing is constrained by the expectations associated with specialized writing on art. And so, today I am allowing myself a conversational tone and permission to attack the project that is the subject of this article from another angle. And then, with the climatic and technological catastrophe predicted, including in the images and words of the enigmatic Anton Bequii, who is the subject of Aquin’s new book, it seems to me that the time is right less for analysis than for action and, echoing a concern of Bequii’s, for speaking out.

Early in the planning for his project, Aquin asked me to contribute as an author. Although interested at first, I realized that it wasn’t the direction I wanted to take with my writing. So, I encouraged Aquin to write his own texts. After all, I told him jokingly, maybe he had inherited his uncle’s writing talent. Disappointed, he told me how difficult it was for him to write. I responded that that is true for most people, me included, and that the only distinction between people who write and people who don’t is that some people, despite the challenges inherent to writing, in spite of themselves, and in defiance of their incapacities, nevertheless undertake to write. So, Aquin got to work and, as the essays written for his project show, he did so brilliantly.

I’m telling you all this for two reasons. First, I want to justify my inability to speak objectively about Aquin’s project, and I hope that this article will shed a bit of light on the reality that underlies this deficit of objectivity. Second, I want to encourage everyone who wants to write to go ahead and write, to break free of the obstacles that keep them from writing and, in doing this, to bring into their lives the liberating power of writing, which is just one specific manifestation of speaking out. In the world as it is today, it seems urgent to collectively reappropriate the lost agora of speech. We can count Benoit Aquin among those who feel and understand this urgency. And there are no doubt many others, several even ignoring it.

Don’t worry, I’ll still tell you a bit about Aquin’s project so you can know what it’s about. Aquin adopted, for the time being (might we not expect that an enlightened museum will eventually offer to exhibit this major work of Quebec photography?), the form of a book containing images and texts. Essentially, the visual corpus is composed of photographs taken from one end of the world to the other, from Montreal to Tokyo, from Katmandu to Paris, from São Paulo to Delhi, from L’Anse-au-Griffon to Moscow, not to mention Los Angeles, New Richmond, Guatemala, Shibuya, and La Patrie. For Anton Bequii is both the creator of the images and the self-fictional and anagrammatic character – a globetrotter, a sort of contemporary Ulysses – that Aquin has created to speak for him. Engaged in a crusade against the totalitarianism of technocratic society, he will eventually be swept away in his esoteric, profoundly spiritual quest.

Some will say that Bequii’s photographs, which insistently show telecommunications relay towers or people leaning over their telephones, are documentary in nature. This would be accurate if, in contrast to the approach with which we usually associate the name of Benoit Aquin, they were not haunted by the psychotic character inherent to every mind that, like Bequii’s, feels alienated, even a little, by technology. These days, when technology is pressing with all its weight on a crumbling world, don’t you feel this alienation too?

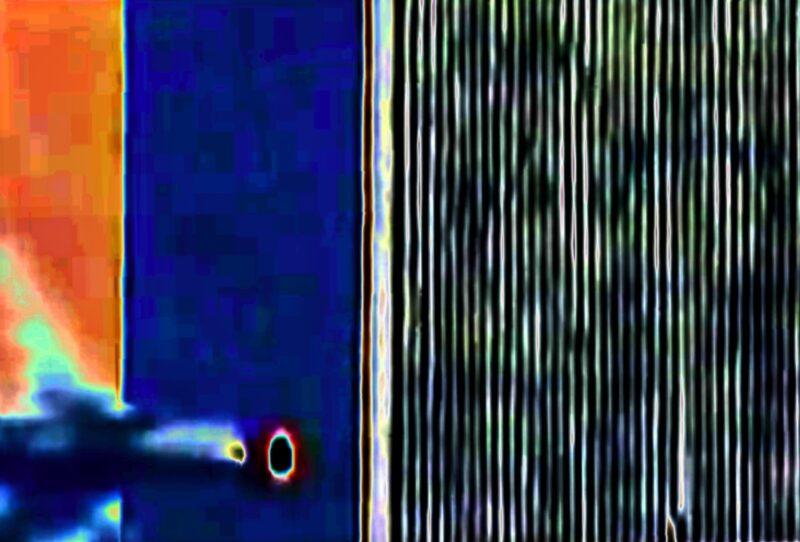

Aside from the photographs, the book contains a number of dazzling visions – screen captures deformed by digital triturations that Bequii performed to reveal the grasp that algorithms have on the contemporary collective psyche, which is apparently incessantly manipulated by the propaganda that floods the mass media and the Web. Through this grouping of psychedelic-tinted images, deliberately polluted with digital artefacts, Bequii builds an inventory of historical events, from the September 11, 2001, attacks to the 2019 uprisings in Hong Kong, that have helped to determine contemporary geopolitics and consolidate the dumbing down and radicalization of the masses, who are more and more enslaved by the globalized yoke of technology. It is as if, under this yoke and in Bequii’s head, there were in fact no more real history, only history distorted by technological ideology, through propaganda. In other words, history as a terrifying myth, or as an apocalyptic nightmare.

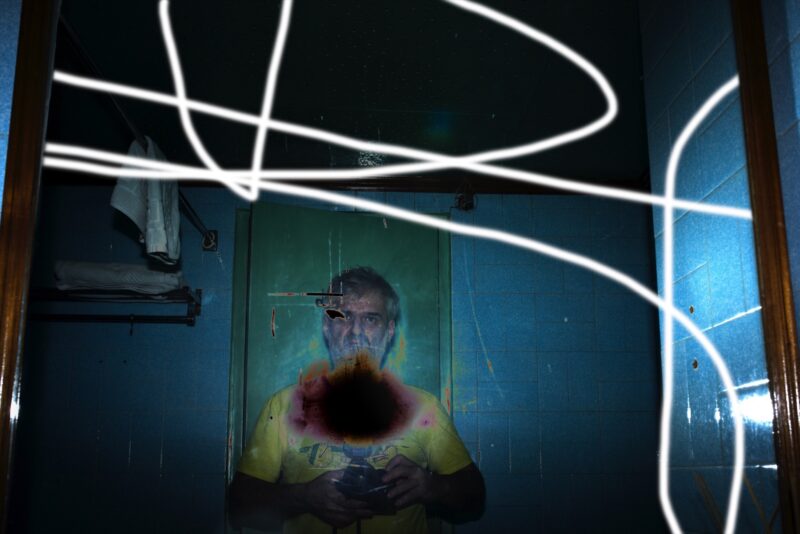

Several self-portraits by Bequii also punctuate the book, inscribing the character in the book’s narrative, helping to familiarize us with him. But it is above all in a group of letters that he addresses to his muse, the no less enigmatic Elena, that Bequii reveals himself and the significance of his work. Immersed in the writings of philosopher Jacques Ellul (1912–94), some of whose texts are sprinkled throughout the book, Bequii insistently expresses his fear of seeing the collective memory being definitively subjected to the polarization and fragmentation induced by the binary language of algorithms. Rather than allowing himself to be drawn into the pessimism of conspiratorial thinking, Bequii chooses the path of courageous uprising: to oppose material rationality with the intuitive powers of spirituality, which is to be sought in love, in beauty (the “signpost of mystery,” he says), in passion, in creation, in nature. Finally, it is within nature that Bequii, at the end of the book, seems to have been swallowed up by the ether of the fourth dimension.

What does this disappearance mean? As I closed La dimension éthérique du réseau par Anton Bequii, I thought that there still exists, in spite of everything – in spite of propaganda, in spite of the culture industry and its institutions, and in spite of the death programmed by technology or by climate emergency – a space in which art persists in speaking the crying need for transcendence. An art of resistance in which the void, “source of all creation,” is accepted as a deep and fertile silence, invested with unnameable meaning. An art in which words are written beyond metaphors, in which images are able to show the unsayable hinterland of the real. An art in which, in the hollows, in the interstices, and between the pages, we hear the echo of a rediscovered speech that will live through us, rebellious, disobedient – or else we too will soon have to resolve, but in a different way than Bequii, to disappear. As we await the uprising, what remains to us are the liberating possibilities of writing. Translated by Käthe Roth

Author’s contextual addendum: The text above was written before the COVID-19 pandemic struck Quebec. The crisis sheds light on the importance of the dynamic of networks in contemporary society and, so doing, on the visionary nature of La dimension éthérique du réseau par Anton Bequii.

Benoit Aquin has been exploring human life and the environmental question through his photographs for more than three decades; in the 2000s, he sharpened his focus on ecological issues. He has dealt with subjects as varied as hunting, desertification in China, and the Yamaska River. His works have been shown in exhibitions, published in artist books, and are in museum collections. He is represented by Galerie Hugues Charbonneau in Montreal. www.benoitaquin.com

Artist and author Alexis Desgagnés lives in Montreal. He teaches art history at a college and is interested in critical pedagogy, eco-syndicalism, permaculture, and Taoism. In 2016, he published Banqueroute (Les Éditions du Renard), a collection of photographs and poems. His next artist book, Ammoniaque, is forthcoming.