[Summer 2020]

By Blake Fitzpatrick

Uranium is an unstable element. It breaks down over time – a very long time. Naturally occurring uranium-238 has a half-life of 4.468 billion years, meaning that it takes that amount of time for half of the uranium to transform into other elements in a radioactive decay chain. The elements in the decay chain are called “daughters of uranium,” and each daughter is the progeny of the “parent” isotope that precedes it. This most unstable and volatile family has been harnessed by the nuclear industry for both medical purposes and militaristic ones, such as atomic weapons (U-235 is a fissile isotope necessary to sustain a nuclear chain reaction). Metaphorically gendered, the “daughters of uranium” decay over time, releasing radioactivity into environmental and biological pathways in the present and for generations to come.

Artist Mary Kavanagh explores the legacies of nuclear culture in related exhibitions: the multi-faceted Daughters of Uranium and Trinity 3, a two-channel video work extracted from the larger project.1 The exhibitions reach across the nuclear Anthropocene to build connections between nuclear history and its lived effects, the nuclear site and irradiated bodies, nuclear reflection and material evidence.

Trinity Site in New Mexico anchors the exhibitions. Conducted under the auspices of the Manhattan project, the Trinity test took place on July 16, 1945, deep in what was then the Alamogordo Bombing Range of New Mexico. The purpose of the test was to explode an atomic “device” to prove the viability of the bombs that were used in attacks on Hiroshima and Nagasaki three weeks later.

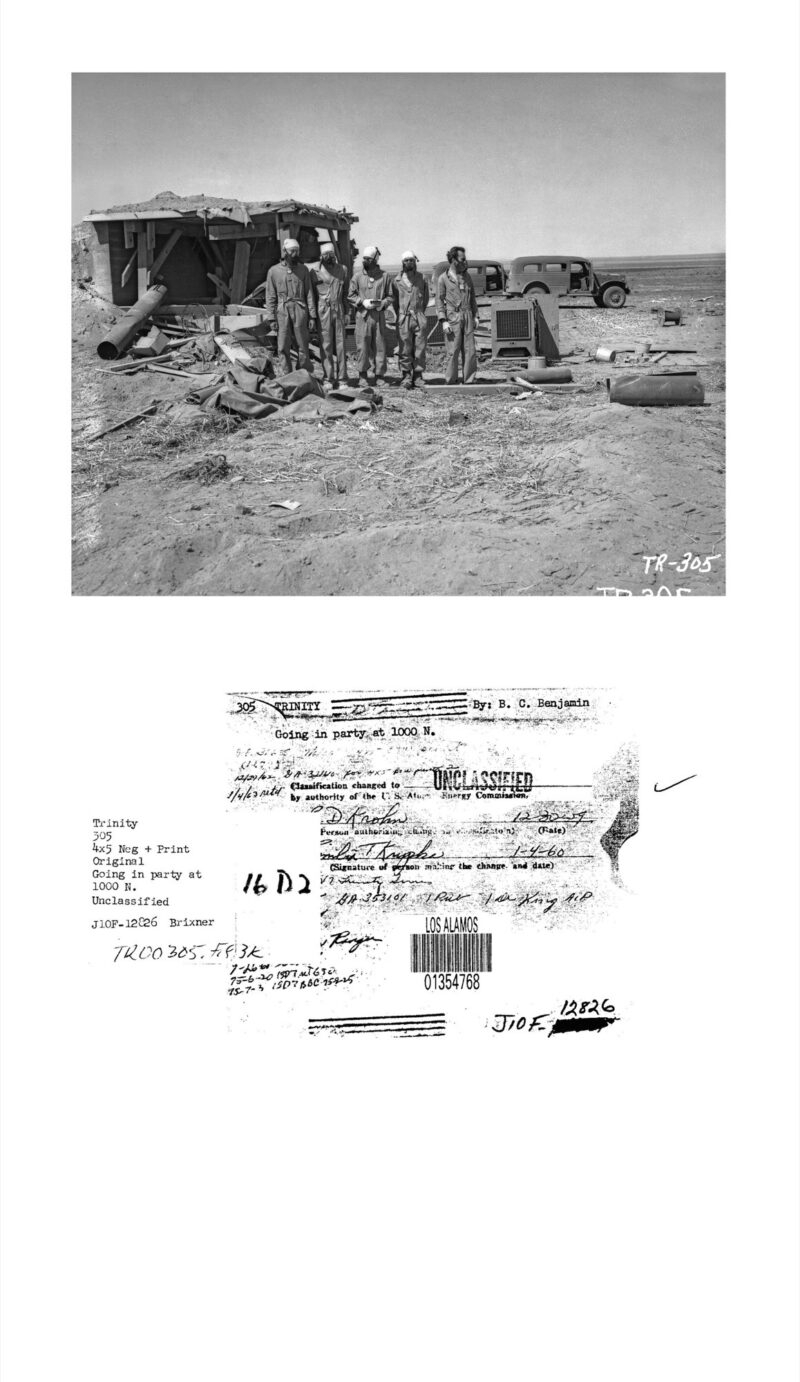

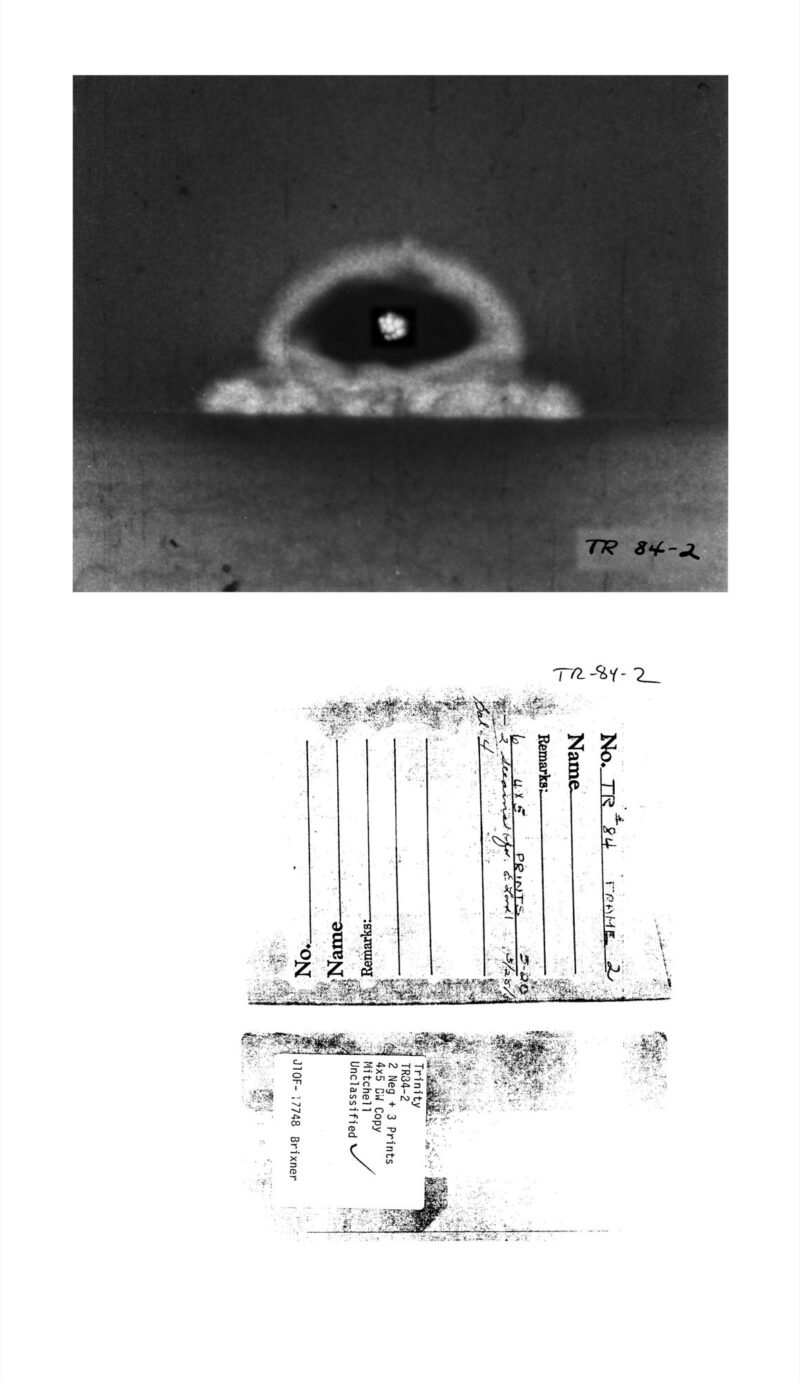

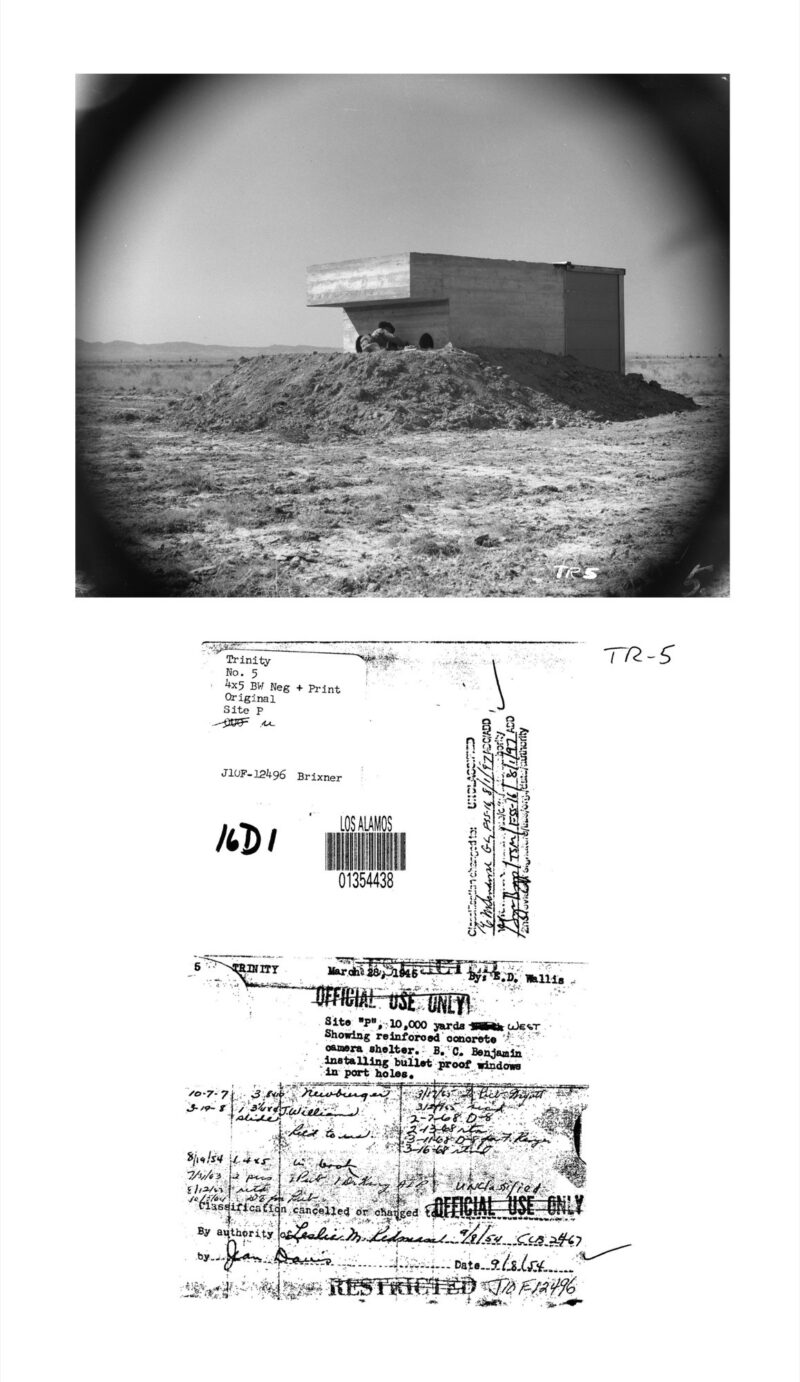

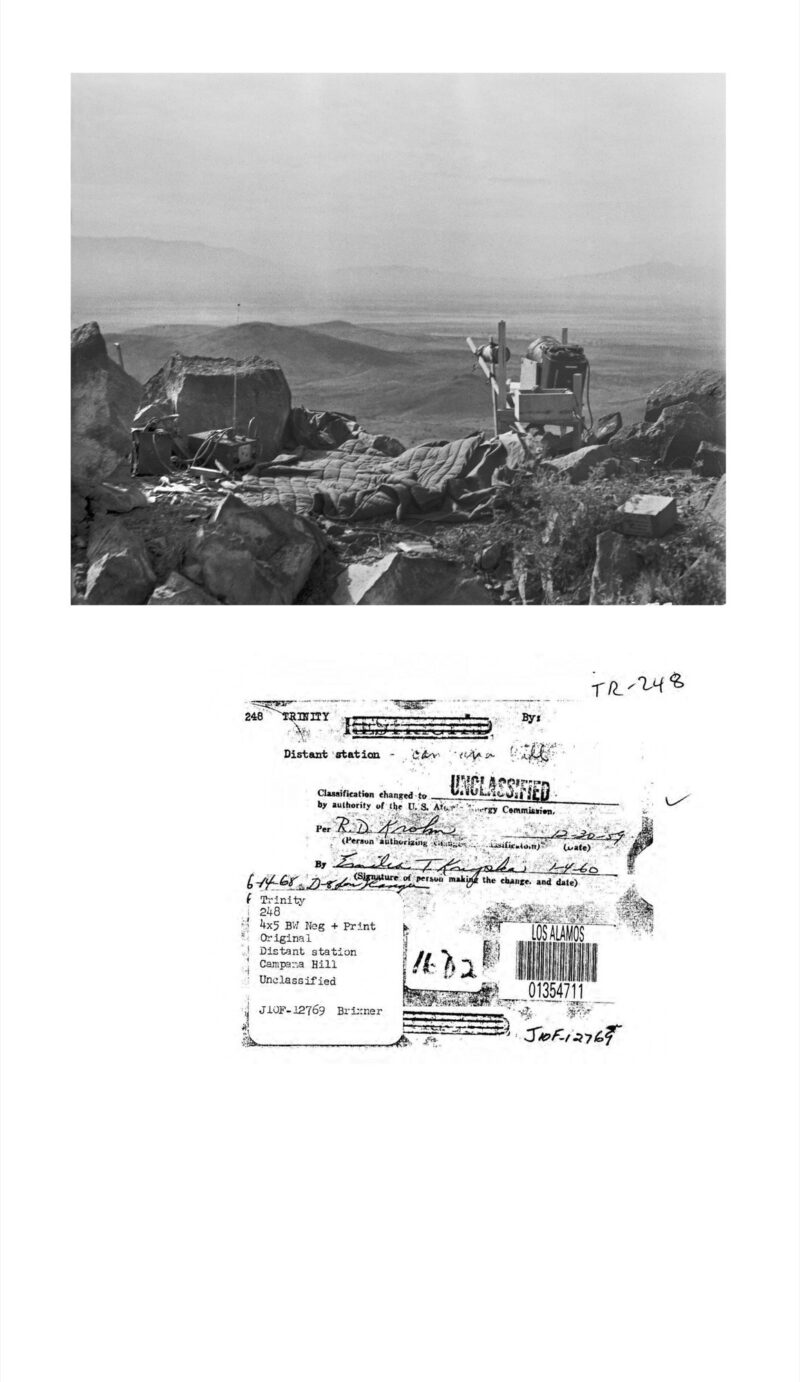

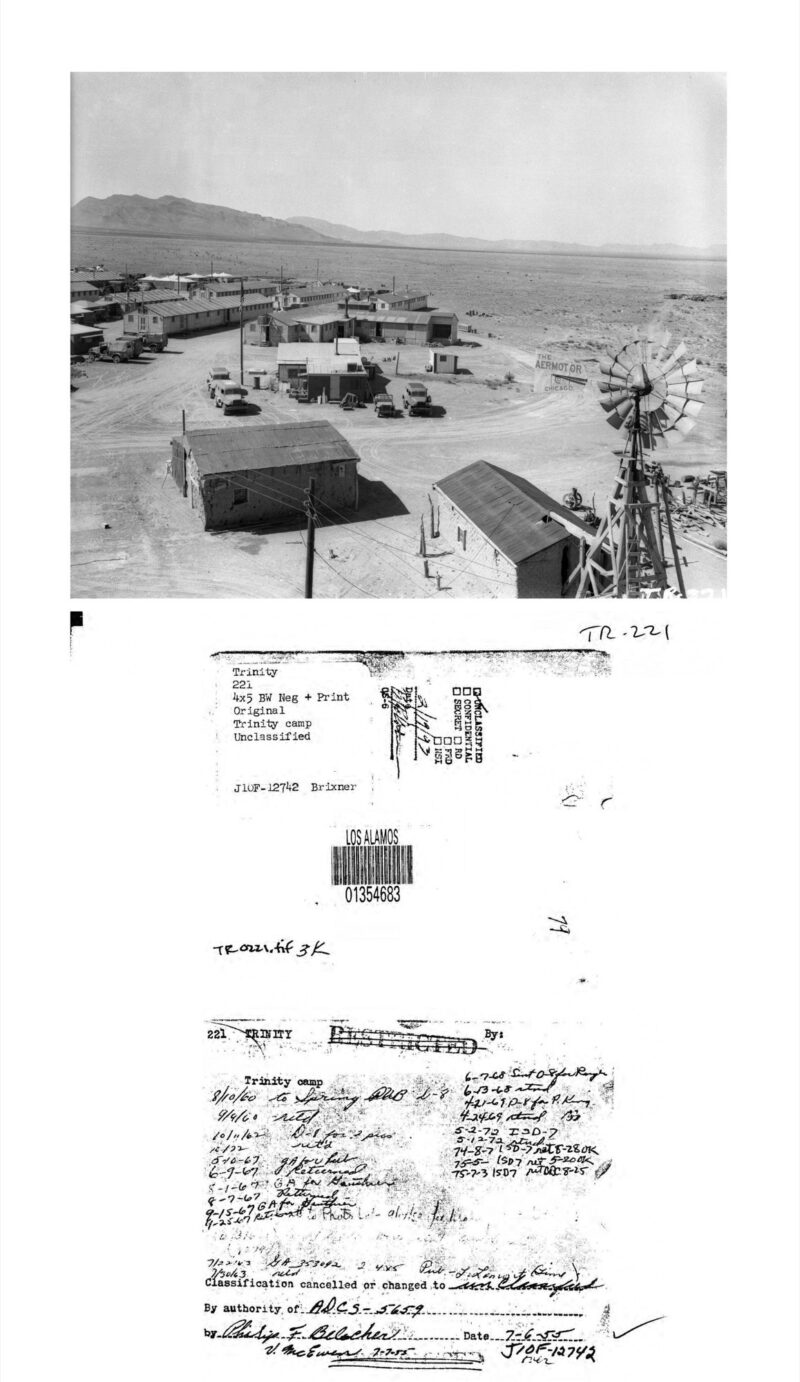

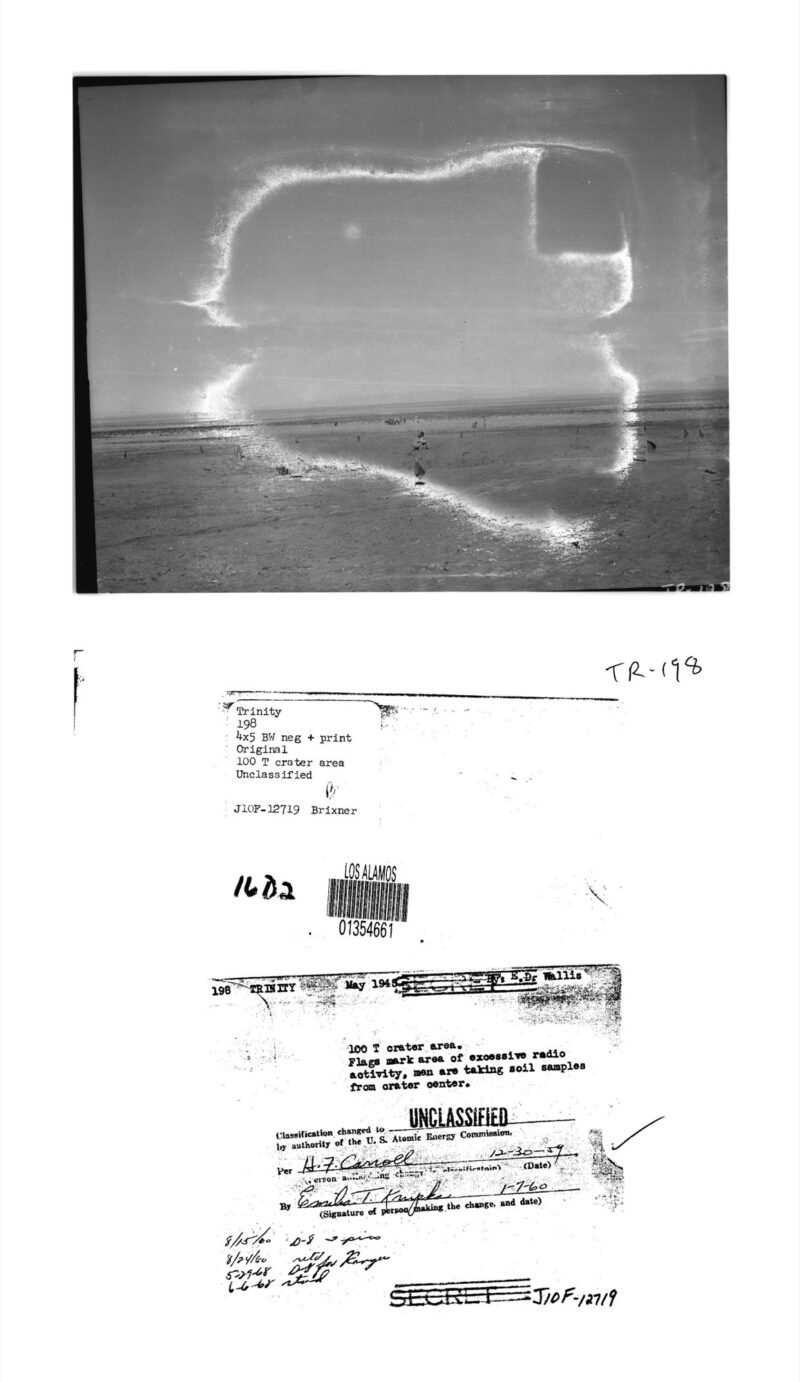

John O’Brian writes, “Wherever nuclear events occur, photographers are present. They are there to not only record what happens but to assist in the production of what happens.”2 The Trinity test was thoroughly documented via both photography and film. In a series of photographic images titled Trinity Archive, 1945–46 (2019), Kavanagh reproduces thirty-four photographs from an archive of more than eight hundred taken by the official “atomic photographer,” Berlyn Brixner.3 The photographs depict aspects of the bomb’s construction and iconic images of its explosion, with declassified metadata for each image on its reverse. A conceit for any archive is that of completeness. Brixner’s archive of eight hundred images is purported to be the most complete depiction of the test. Yet, for every archive there is what Allan Sekula called a shadow archive.4 Beyond the dominant narrative of triumphalist militarism, the shadow archive includes the entire social terrain of nuclear experience, an archive of invisible others, silenced and sacrificed by the nuclear-military-industrial-complex. Photographs are partial records, and what can be seen carries a deadly inverse in what can’t be seen–cancerous fallout, radiation, trauma, and the truth about it all.

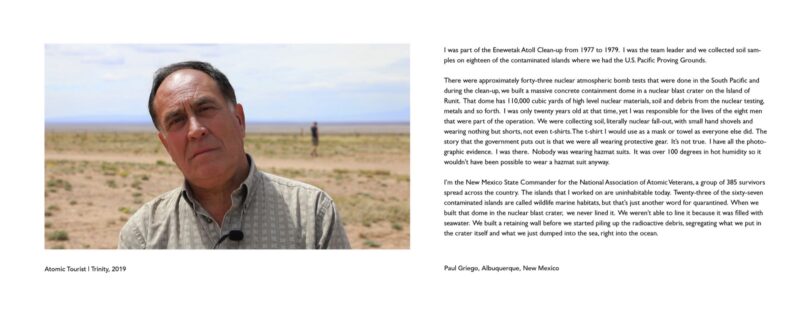

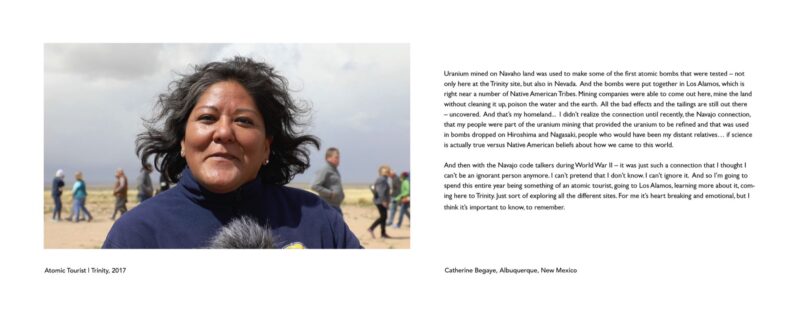

Paul Virilio contends, “War is at once a summary and a museum . . . its own.”5 Trinity site is also its own museum. This precursor to atomic death is now imbued with commemorative significance. The White Sands Missile Range, an active weapons-testing facility, controls the site and hosts an open house on the Trinity grounds on the first Saturday of every October and April, attended by thousands of visitors. Kavanagh has conducted over two hundred video interviews there.

In the two-channel video piece Trinity 3 – presented as an impactful solo work at the Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery – archival sequences of military personnel building the bomb are juxtaposed with contemporary video portraits and interviews at the commemorative site in a looped sequence that includes the landscape itself – starkly beautiful, evocatively silent. Looking back and forth between past and present, it seems as if the citizens are speaking back to the images on the adjacent screen, grappling with their full implication. Thought ranges over this site, unfolding in terms that include the spiritual, the environmental, and the historical – a history of the present as caught in the voices of the multitude.

One of Kavanagh’s strategies is to actualize nuclear experience by bringing the evidence of atomic experience into the gallery. In side-by-side vitrines, a grid of trinitite remnants sits next to a jar of rubble from Hiroshima. Trinitite is a glassy mineral formed when the heat of the Trinity test melted the desert sand into a radioactive surface. It remains mildly radioactive. The Trinity test thus adheres to these radioactive fragments, becoming what Susan Schuppli refers to as a living analogue – an active material witness to the atomic event.6

Iterative connections between works run through the exhibition. Kavanagh has installed a stack of six lead bricks, each two by four by eight inches, on the gallery floor. Lead-206 is the final element in the radioactive decay chain. It is the last of the “daughters of uranium,” the stable one. The lead bricks on the gallery floor are thus a counterpoint to the trinitite in the vitrine. The one actualizes radioactivity, whereas the other marks the terminal point of the radioactive decay chain.

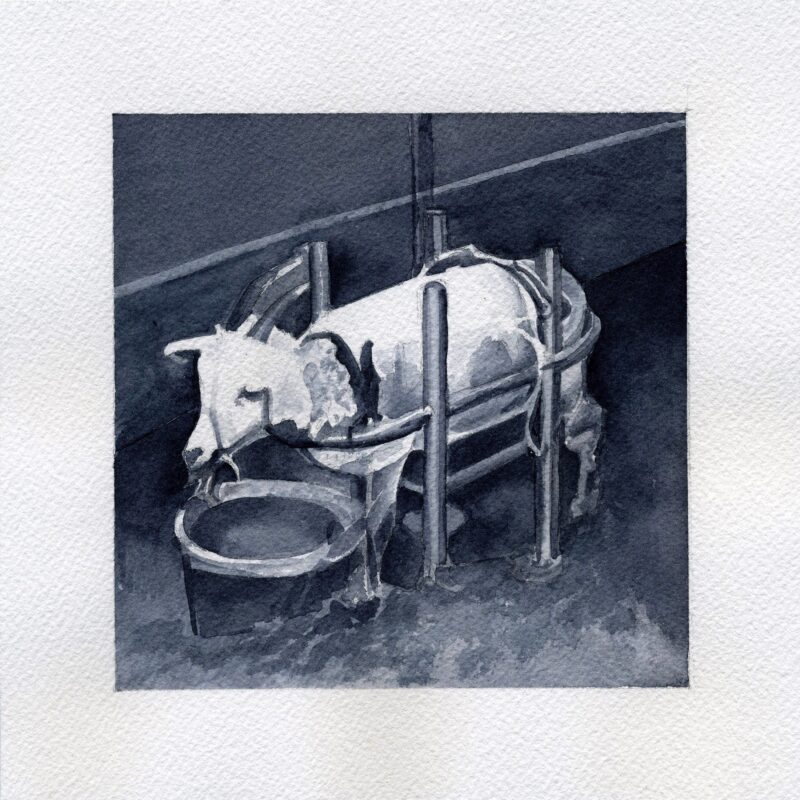

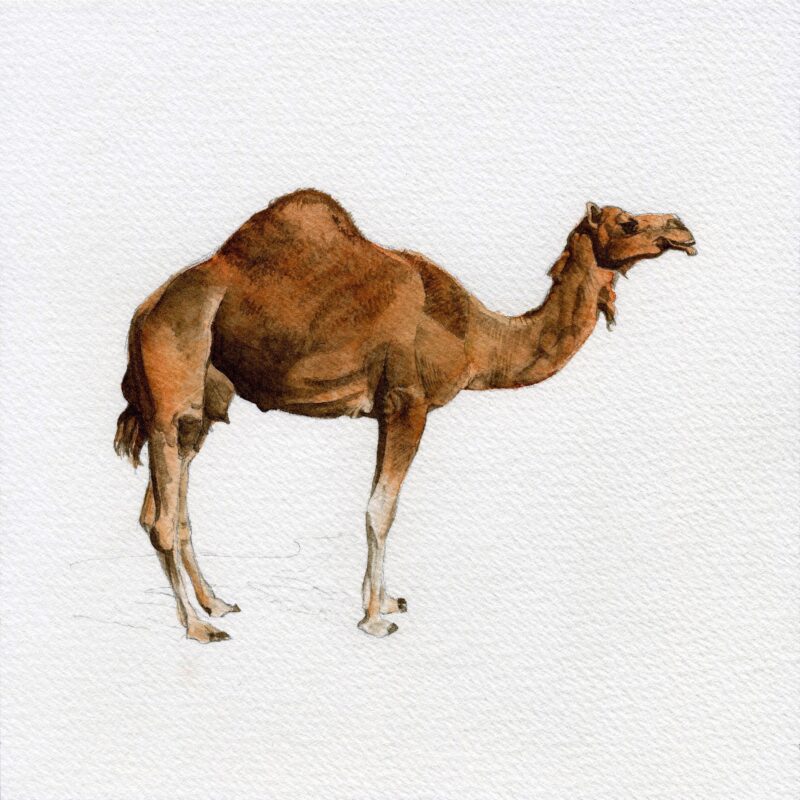

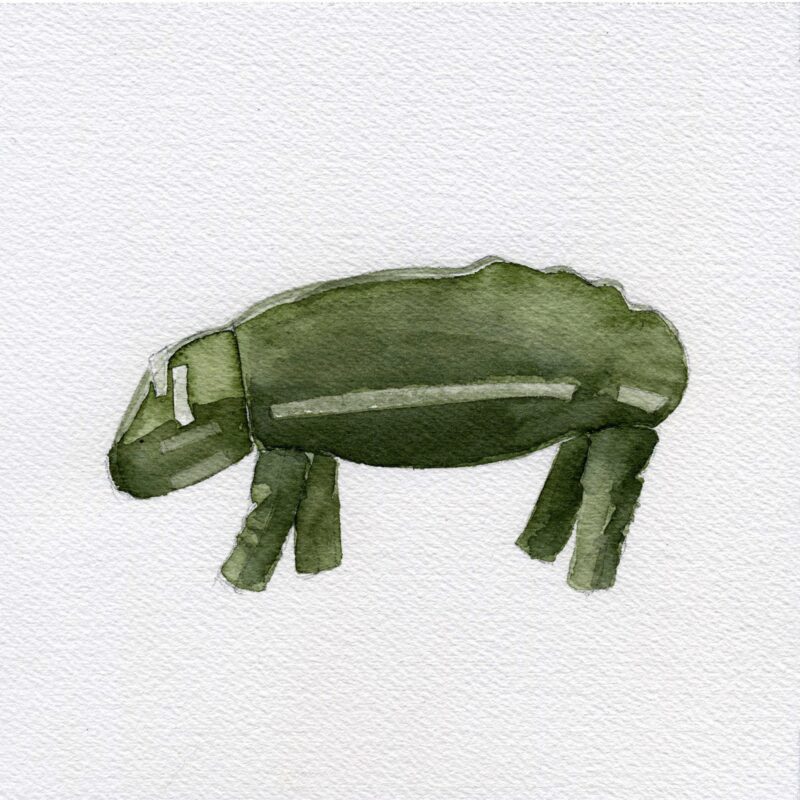

A series of framed watercolours is titled Rain of Ruin (2011–19). The title is a reference to a warning issued by President Truman to Japan one day after the Hiroshima attack, as published in the New York Times and reproduced in another of Kavanagh’s works. The watercolours include depictions of non-consenting subjects – a brown rat, a desert hare, and a goat – based on a documentary photograph taken as part of Operation Crossroads, conducted on the Bikini Atoll in 1946, during which over three thousand animals were loaded onto ships and subjected to a massive atomic weapons test. We might think here of Noah’s Ark turned deadly. Many of the subjects depicted reference other works in the exhibition, such as a drawing of a pig and the corresponding three-dimensional object, Pig Suit (2019). The artefact replicates a chemical experimentation suit used to investigate nuclear, biological, and chemical weapons on animals as proxies for humans. Proxies run through the exhibition, and, as Kavanagh reminds us, in the nuclear era we are all guinea pigs.

The use of bodily proxies extends to Hands, to Hold (2019) and Rosa the Beautiful (2019). These sculptural works replicate nuclear bodies and living organisms in cast uranium glass that “fluoresces” green under ultraviolet light. Hands, to Hold presents a table of mimetic proxies – yucca plants from New Mexico, seed pods from nuclear sites in Ontario, and the hands of an artist. In the life cycle of cells, nature holds a record of exposure to radioactive materials, one that never goes away. In Rosa the Beautiful, a cadaver of glowing green legs is suspended in a darkened space, purpose built in the centre of the gallery. Melded with uranium oxide, “Rosa” personifies the daughters of uranium; its green glow evidences radioactivity in the amputated spectre of a radiological body, specifically gendered.

How does one see the toxicity of nuclear fallout in the air, the home, or the confines of one’s own body? The politics of air is referenced in works depicting Kavanagh’s family history as it brushed up against airborne illness, and a compelling sequence in the video Trinity depicts a soldier in a hazmat suit, breathing through a respirator. Peter Sloterdijk notes, in Terror from the Air, that gas warfare, or “atmoterrorism,” began during the First World War (1914–18). From that point on, the air as a commons turned deadly, political – the air has, as Sloterdijk suggests, “lost its innocence.”7 When air becomes political, breathing becomes a witness to politics.

There are three related works in the exhibition that reference air and the act of breathing as an embodied politics. Glass Breath (2014) is composed of glass vials formed by the exhalation of the artist’s breath. Drawing Breath/Infinity Series (2017–19) performs the precise inscription of lines drawn across paper, through the act of breathing. Each work makes the invisible (breath) visible. The drawing Tumour Timeline (2011–18) complicates and implicates both pieces. The air in the glass vials of Glass Breath passed through the artist’s lungs; the lung has a tumour. We might say, following Sloterdijk, that the air that formed the vials has also lost its innocence. This is Kavanagh’s forensic work turned inward, the curation of the body in time and illness, an attempt to make the interior visible through the act of drawing. In this work, drawing becomes a way of turning the body inside out, a visualization of bodily burden in an overwhelming nuclear context.

1 Mary Kavanagh, Daughters of Uranium, March 2, 2019–April 28, 2019 at the Southern Alberta Art Gallery, Lethbridge, and September 27, 2019–January 26, 2020 at Founders’ Gallery, the Military Museums, University of Calgary. Trinity 3, February 13, 2020–May 10, 2020 at the Kitchener-Waterloo Art Gallery, Kitchener.

2 John O’Brian, “Introduction: Through a Radioactive Lens,” in Camera Atomica, ed. John O’Brian (London: Black Dog Publishing, 2015), 11.

3 Berlyn Brixner (1911–2009), Mary Kavanagh, and I are members of the Atomic Photographers Guild, a global group of photographers dedicated to making the atomic subject visible.

4 Allan Sekula, “The Body and the Archive,” October 39 (Winter 1986): 10.

5 Paul Virilio, Bunker Archelogy (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 1997), 27.

6 Susan Schuppli, “Radical Contact Prints,” in Camera Atomica, ed. John O’Brian (London: Black Dog Publishing, 2014), 279–91.

7 Peter Sloterdijk, Terror from the Air, trans. Amy Patton and Steve Corcoran (Cambridge,MA: MIT Press, 2009), 109.

Mary Kavanagh’s field of research includes environmental policies, war technology, and history of science. A professor in the art department at the University of Lethbridge in Alberta, she has documented military, nuclear, and industrial sites in Canada, Japan, and regions of the United States (including Utah, Alaska, and Nevada) in her photographs. For twenty years, her projects have been featured in solo and thematic exhibitions. She is a member of the Atomic Photographers Guild, an international collective formed in 1987 to record the nuclear age.http://people.uleth.ca/~mary.kavanagh/

Blake Fitzpatrick is a Toronto-based photographer, curator, and writer. His research interests include the photographic representa- tion of the nuclear era, visual responses to contemporary milita- rism, and the post-Cold War history, memory, and mobility of the Berlin Wall. He has exhibited his work in solo and group exhibitions in Canada, the United States, and Europe. His curatorial projects examine the work of contemporary artists who respond to war and social conflict. His writing has appeared in numerous journals and anthologies. Fitzpatrick holds the position of professor and chair in the School of Image Arts, Ryerson University.