[Hiver 2021]

An Interview by Chuck Samuels

Chuck Samuels is an occasional freelance critic who lives and works in Montreal. This is the third in a series of interviews with Chuck Samuels appearing in Ciel variable. He has also published articles in such Canadian contemporary arts magazines as MIX, Fuse, and Vanguard (co-written with Moira Egan). Samuels contributed a chapter to Women and Men: Interdisciplinary Readings on Gender, edited by Greta Hofmann-Nemiroff (Fitzhenry-Whiteside, 1987).

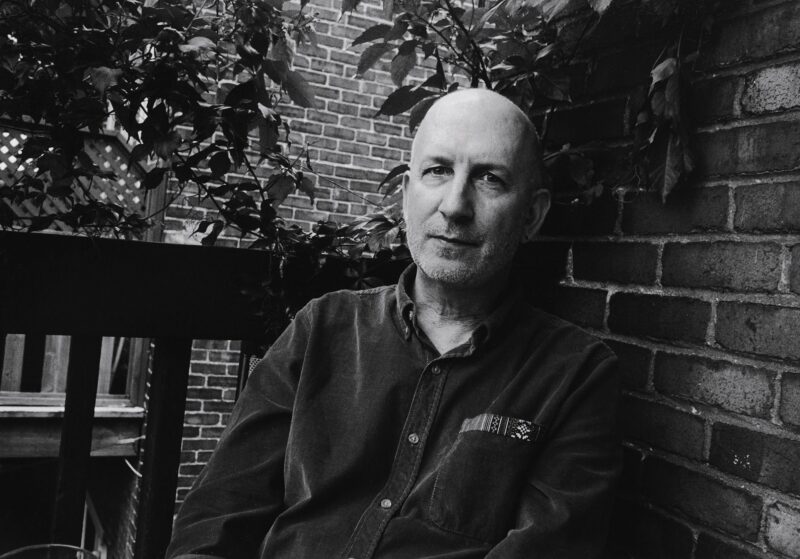

Since 1980, Chuck Samuels’s photographs and videos have been exhibited, published, and collected extensively in Quebec, Canada, and abroad. His photographs are in numerous public and private collections in Canada, France, Mexico, Belgium, and the United States. Chuck Samuels lives and works in Montreal. Two of Samuels’s most recent works, On Photography and After, were presented at Espaces F in Matane in the fall of 2020. Another, larger exhibition and a major publication are planned for early 2021 and are discussed below.

CS: It has come to my attention that you recently completed three new bodies of work and that these new projects sound distressingly similar to your previous work. What compels you to repeat the same thing over and over? Is it a failure of imagination?

CS: No, not at all! To begin with, they are not precisely the same ideas or images; rather, they are variations on the similar themes. As you know, I’m totally preoccupied with photography and how it works as well as how it doesn’t work. Most of my forty-year practice has, in one form or another, involved poking and prodding into various photographic archives and practices in order to interrogate these questions. And no, it’s not a sign of creative deficiency – rather, it is an obsession. As one of the jurors at my thesis defence so eloquently exclaimed, “It’s like a scab – you have to pick at it, pick at it, pick at it!”

CS: Besides the new works, I heard that you’re coming out with a publication and that you’ll be having an exhibition that brings together six of your projects ranging from 1991 to 2020. Why don’t we start our discussion by talking about the publication and why anyone would be interested?

CS: If you had bothered to do some pre-interview research, you would know that my work is better known in Europe and the U.S. than it is in Canada (although, admittedly, it is not that well known abroad) and that an enviable number of local and international partners signed on to collaborate with me on the book.

To answer your question, in 2014–15, I started thinking about producing a publication that would be the first book entirely dedicated to my work, and this got me to reflecting about what form it could take. It occurred to me that a publication that dealt exclusively with my solo projects in which I photographed myself in order to confront assorted characteristics of photography, including Before the Camera (1991), Before Photography (2010), and The Photographer (2015), could be very interesting.

Looking back at these and other earlier works, I realized that throughout my career I was trying to delve ever deeper into various aspects of photography, that I was, in an absurd sense, trying to incarnate, or to “become,” photography. So the book, I thought, could resemble an academic tome on photography with chapters dedicated to different facets and histories of the medium and its use, only I would be present in virtually every image. I would title the book Becoming Photography. The more I thought about this, the more it seemed preposterous enough to work. It was clear, however, that I would need to produce a few new series to build upon the coherent approach already apparent in my work.

CS: Can you talk about these new projects and their similarity to, and differences (if there are any) from, your previous work?

CS: As early as 2014, I envisioned a project of remaking the remakes and had even put together a preliminary list of appropriation artworks that I could appropriate. This idea evolved into After, a series of eighteen photographs and four videos. It is a project in which, once again, I infiltrated existing images, only these images were, themselves, remakes of existing images. Although it’s true that After shares many qualities with my earlier works but with an added and generous dollop of vertiginous self-referentiality. After features reverential but risible remakes of appropriation works by Dara Birnbaum, Joan Fontcuberta, Samuel Fosso, Kathy Grove, Sherry Levine, Yasumasa Morimura, and others.

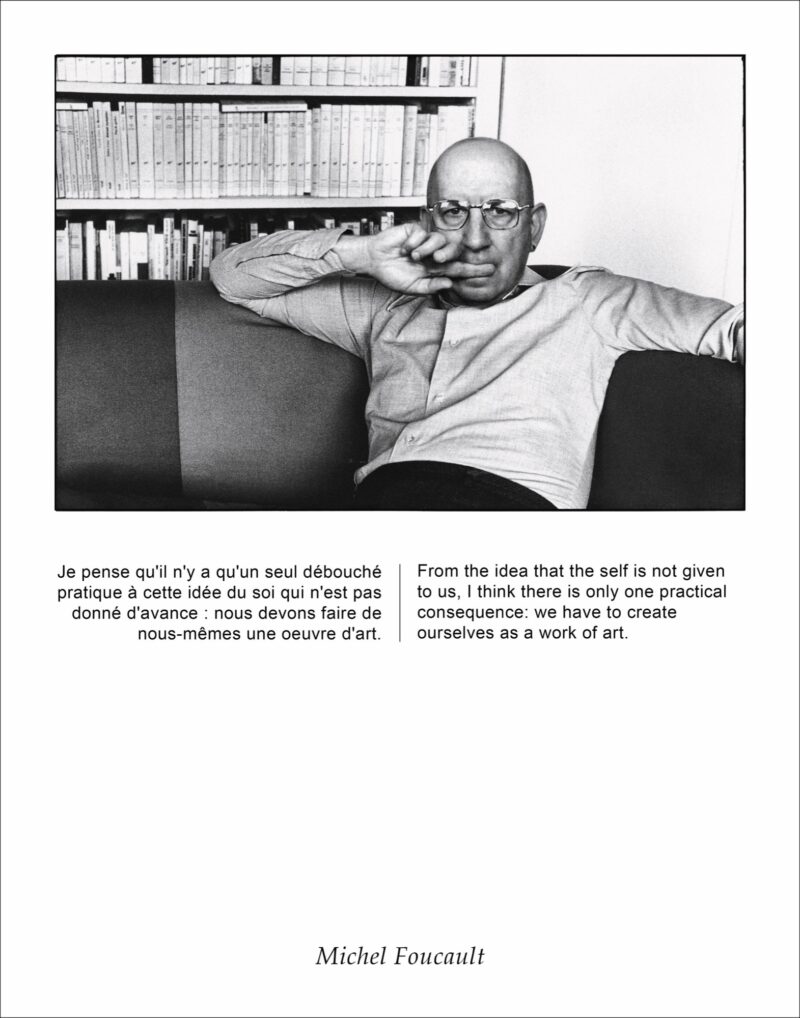

I had also considered a project that would address the image and words of the critic, a series that would echo my use of text and image in earlier series, such as The Mission of Photography… (1985), Easy Targets (1990), and The Demotivational Series (1997). The series focused on the image and the words of critics (critics who, the viewer may notice, bear an alarming resemblance to me), and I planned to snatch the critics’ quotations out of their original frame of reference and create a setting in which their words would, against their will, act as a rigorous defence of my project. In the course of my research, I was able to identify thirty photographic portraits of critics from whose writing I was able to find appropriate quotations. These included photos of, and texts by, Roland Barthes, Walter Benjamin, John Berger, Simone de Beauvoir, Michel Foucault, Lucy Lippard, Susan Sontag, and others. In addition, I produced a video that further ruminates on the ease in which decontextualized words could be manipulated. The project is titled On Photography after Sontag’s seminal collection of essays from 1977.

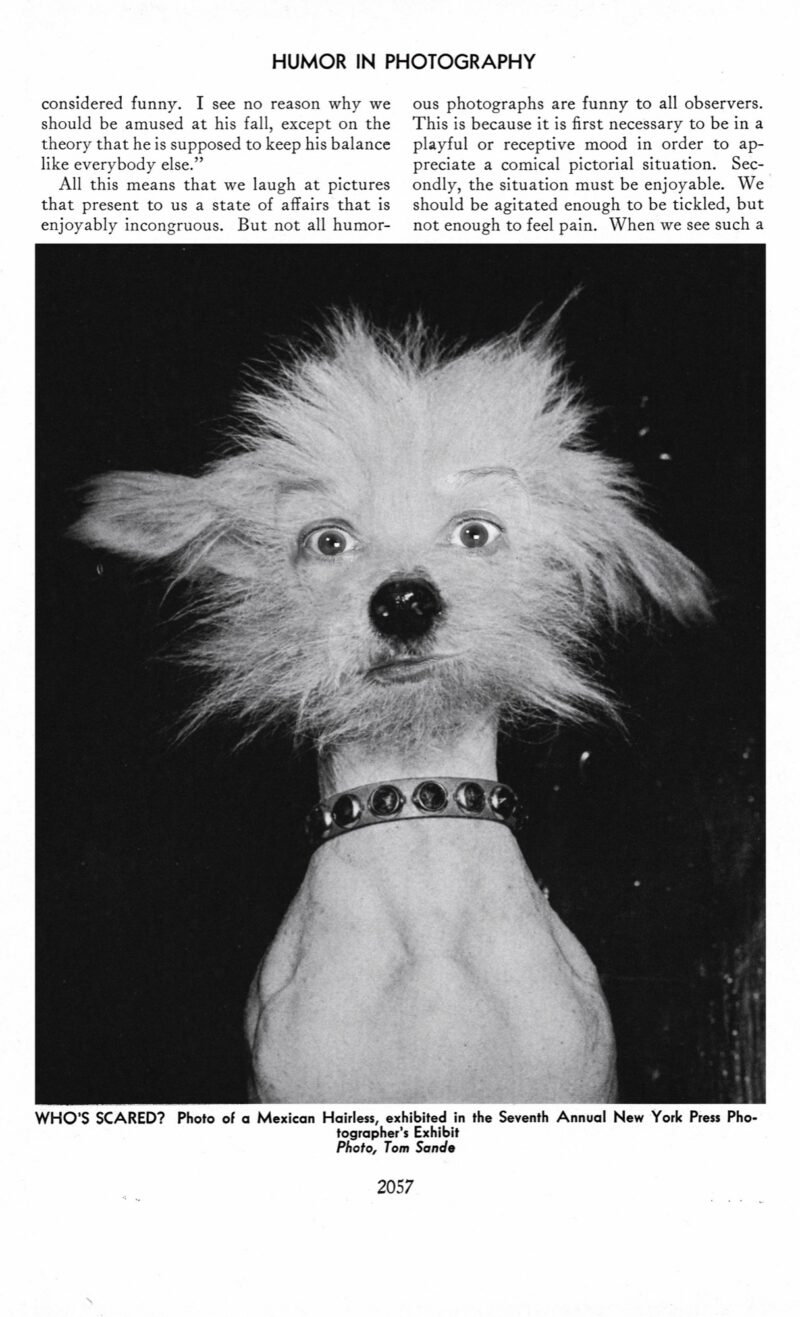

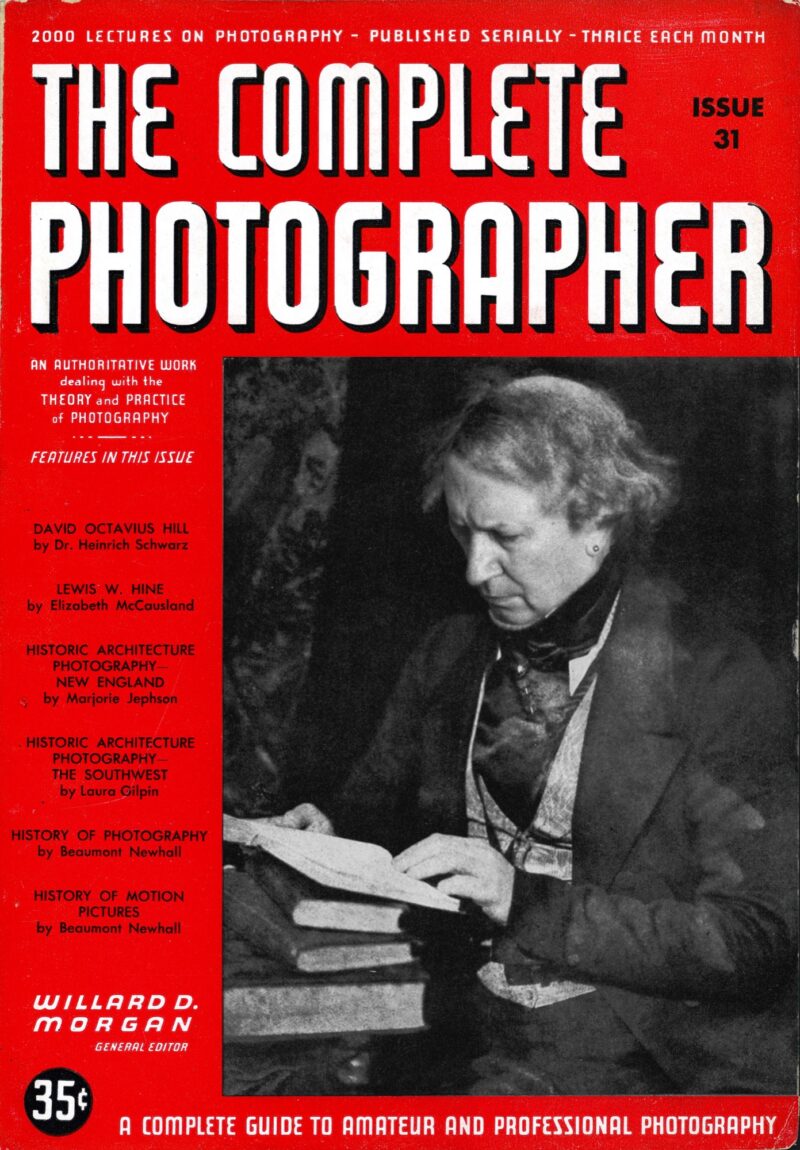

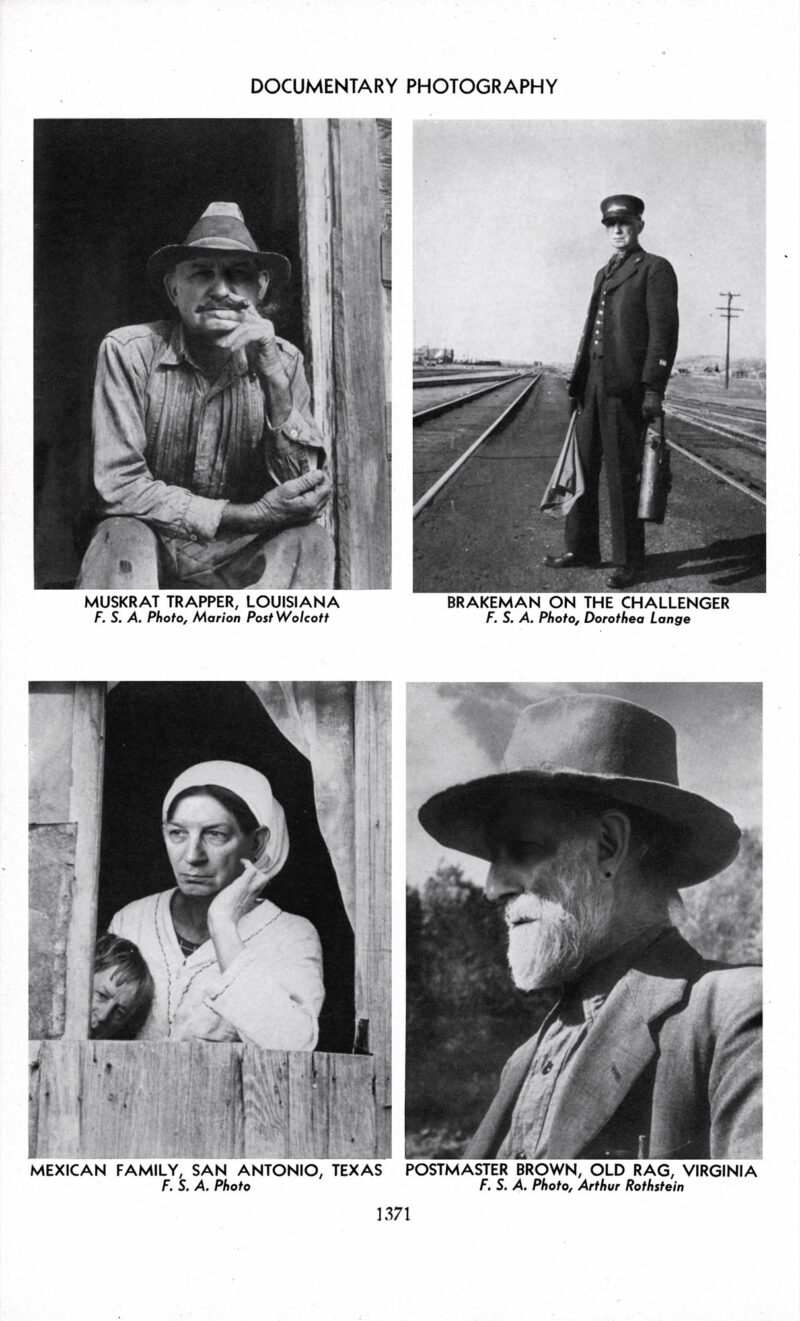

In 2019, while organizing my basement, I chanced upon a stack of issues of The Complete Photographer, an American photography magazine from the 1940s, probably handed down to me by my father, who initiated me into the practice of photography when I was eleven years old. Presented with a first-rate opportunity to generate a new set of inimitable imitations that would direct the viewers’ attention to the historical function of the photography magazine while, at the same time, permitting me to tamper with several genres of photography that, until then, I hadn’t grappled with, I didn’t hesitate to slip in between the covers of the magazines. This became a third project that I call (and this should come as no surprise) The Complete Photographer.

CS: With regard to these projects, do you feel good about simply continuing to do what you have always done?

CS: In a word, yes. In fact, I would go so far as to say that, overall, I’m extremely pleased with how everything worked out. But, sure, there are certain minor regrets. For example, in On Photography, I would have loved to “become” images of other critics whom I admired and who may have also influenced my thinking and practice. However, I was unable to find the right kind of quotes and/or usable published portraits of Okwui Enwezor, Rosalind Krauss, Laura Mulvey, and Abigail Solomon-Godeau. With After, I would have liked to have remade appropriation works by Barbara Kruger, Vik Muniz, and Jeff Wall but was stymied by logistical and financial issues. If I had more time and funds, I would have engaged with more subjects covered by The Complete Photographer, such as photography dealing with clowns and circuses, criminology, expeditions, farms, fashion, medicine, news, and publicity.

CS: You have obviously spent a lot of resources and energy to produce these series – projects that could be seen as denigrating to photography and photographers. How did you develop this low regard for the practice and its practitioners?

CS: First of all, these projects, like my previous work, were produced with a rather exceptional economy of means. And, while I do raise questions about the practice, my work was done with an almost fanatical devotion to the original artists and with a keen interest in sharing my fascination with photography with an audience.

CS: So would you say that your book is simply a rehash of the exhibition?

CS: No! You need to pay attention – I already said that the publication came first. Initially I was offered a retrospective at Expression, but instead I proposed a large exhibition based on the concept of the book. Both Expression and Plein sud were interested in having the show occupy both venues and they expressed an interest in co-editing the publication along with Kerber Verlag in Germany. The book will be launched at the vernissages of the exhibition in early 2021.

CS: You’ve been doing this kind of work for thirty years now, so would I be misguided to assume that the production of the new projects must have gone smoothly?

CS: Actually, yes. For example, I discovered that becoming Wonder Woman didn’t really become me. You see, I shot After Birnbaum in several public and semi-public locations, and the ill-fitting Wonder Woman costume I wore was prone to the occasional, but embarrassingly scandalous, wardrobe malfunction. There were various other disagreeable surprises, such as having my nose beginning to run copiously and uncontrollably forty-five minutes into a sixty-minute durational performance before the camera for After Gordon.

Furthermore, I was mortified by how old I looked and by how much I had lied to myself about the amount of weight I had gained over the past few years. I recalled some lyrics from a B. B. King/Dave Clark song in which King laments, “Father Time is catching up with me, gone is my youth; I look in the mirror every day and let it tell me the truth.” I learned that if you want to maintain any illusions you may have about how you look when you’re in your mid-sixties, it’s best not to make close-up photographs of yourself. Or videotape yourself disguised as Wonder Woman, particularly if you use high-definition equipment. It can have an appalling effect on your self-esteem.

CS: Please tell me that with the exhibition and book you are, finally, signalling an end to you “becoming” photography and that you will not produce any more series in the same vein.

CS: Who knows? So much photography . . . so little time . . .

CS: So, you are saying that you are going to finish your life working on the same style, which is basically one endless, tedious and essentially meaningless selfie?

CS: Let me tell you a funny story: why don’t you go fuck yourself!