[Winter 2021]

By Zoë Tousignant

It stands to reason that much thought, time, and energy go into the making of a photobook. Fortunately, the work that it involves is usually shared by several individuals who, each expert in their own field, contribute to creating the end product. These individuals most often include a photographer, a graphic designer, a publisher, an editor, an author, a translator, a paper maker, a printer, a bookbinder, and a distributor. The extent of the role that each of these actors assumes, however, is rarely consistent from one instance to the next, and so, with every book made the lines of such relationships are redrawn. For example, I have worked with photographers who have welcomed tremendous input from graphic designers, while others have simply needed someone to execute a pre-established design concept. The same is true even of publishers, who may see their role either as leader or supporter of creative activity.

Every situation is different; yet, when it comes to assigning a photobook’s authorship, the outcome is remarkably predictable: the author of a photobook is the photographer. “But of course it is,” I hear photographers cry in unison. “After all, it’s my book!” Although my intention is not to undervalue the thought, time, and energy invested in a book by a photographer, I nevertheless want to question this status quo in order to explore what an alternative understanding might unlock. What happens when we begin to acknowledge the parts played by all the other contributors? How does recognizing these individuals and relationships expand the way the photobook is perceived at a conceptual level and also, more simply, how it is read?

It bears acknowledging that a clear and firm designation of the author function has been a determining factor of the photobook’s acceptance as a work of art in its own right over the past twenty years or so. It is perhaps precisely to counteract the object’s authorial complexity (and perhaps also its occasional affiliation with the world of popular publishing) that the photobook’s acceptance has rested on the notion that creative genius resides in single individual. Names of photographers are what drive both the acquisition of photobooks by museums and special collections and the publication of canon-building compendiums on the genre. The situation can be compared to the field of cinema, in which the main share of creativity is conventionally attributed to the director, despite the hundreds or even thousands of people who labour over any given film. The notion of the author is a useful device that can help obscure the fact that, behind a single name, an entire industry is at work.

Ewa Monika Zebrowski has been making books since the early 2000s, and they have gained increasing importance in her art practice over the years. Her oeuvre now includes over twenty books, and although some are related to photographic series that she has exhibited in print form, others exist as autonomous works. Usually self-published and printed in limited editions ranging from two to seventy copies, they fall under the heading of the artist’s book, which I would here consider a sub-category of the photobook (in other words, if an artist’s book is photo-based, it can also be called a photobook, but the general term photobook includes many other types of photographic publication). Zebrowski’s books have been collected internationally by such diverse institutions as the National Poetry Library London, the Cy Twombly Foundation, the American Academy in Rome, the Menil Collection, the Farnsworth Museum, the Museum of Modern Art, New York, Stanford University, McGill University, the Banff Centre, the Toronto Public Library, and Bibliothèque et Archives nationales du Québec. Her books lend themselves well to a discussion of the various individuals that contribute to the making of a photobook – in fact, it was Zebrowski’s idea to approach the present essay from this perspective – because of the way she embraces both the concept and the process of collaboration as a productive component in her work. As Zebrowski puts it, she “doesn’t like creating in a vacuum.”

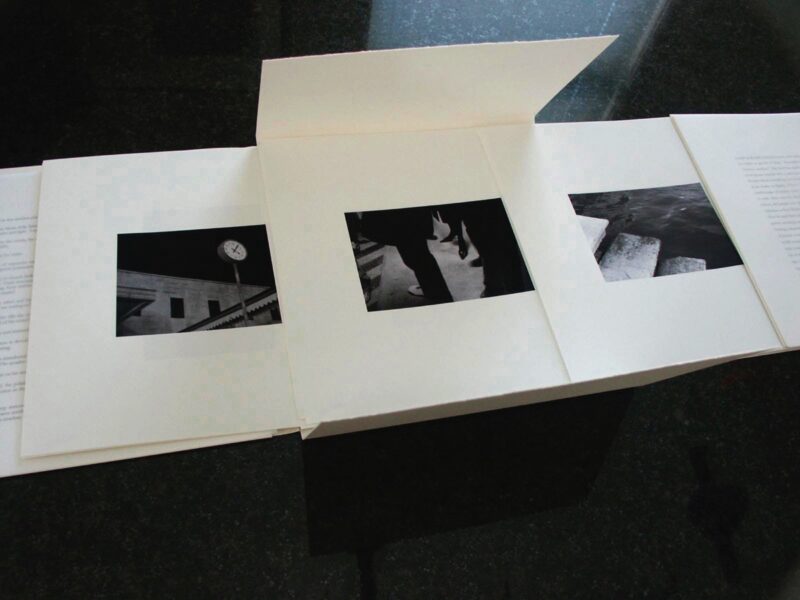

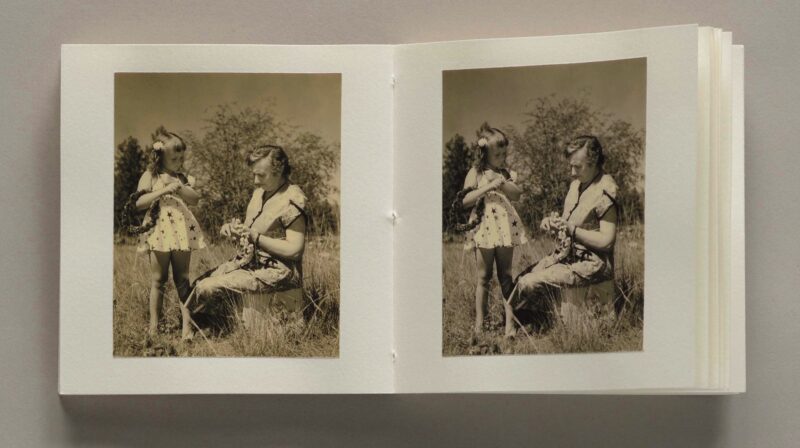

Her first book, My Mother Was There… (Blanc de mémoire) (2001), an autobiographical project that uses personal photographs of her parents as a young couple, was entirely self-made and displays a delicate handcrafted quality that, interestingly, has remained a constant in her oeuvre. Shortly after producing it, she began collaborating with Montreal bookbinder and editor Jacques Fournier, and in 2002 they produced the first of a trilogy of books that Zebrowski calls her “circle of poets,” each being inspired, respectively, by the poetry of Joseph Brodsky, Robert Frost, and Mark Strand. Following a purposefully consistent pattern of size, format, and design, these three works can be seen as the foundational moment of Zebrowski’s distinct artistic exploitation of the book form. The overall aesthetic of the trilogy – for example, the subtle use of embossed or pale typography, the abundance of white space surrounding printed photographs, the ever-so-slightly rough texture of the paper, and the addition of folded book sleeves– has become standard in her practice.

It would be difficult to overestimate the impact that Fournier has had on the development of the artist’s book in Quebec and beyond. Since establishing himself in the 1980s, he has worked on innumerable projects as an artisanal bookbinder, and from 1993 on he was at the head of the Éditions Roselin, a small press specializing in production of limited edition artist’s books. The long list of photographers and other visual artists with whom he has collaborated over the years includes Serge Clément, Adad Hannah, Isabelle Hayeur, Paul Lacroix, Sylvia Safdie, Françoise Sullivan, and Richard-Max Tremblay. Fournier made the decision to retire in 2018, but not before donating the entirety of his studio equipment to Concordia University’s Print Media Department, where he has also lectured. To see and manipulate examples of his creations is to come into contact with a high level of craftsmanship, an impressive attention to detail, and a keen sensitivity to the physicality of books. These are his signature.

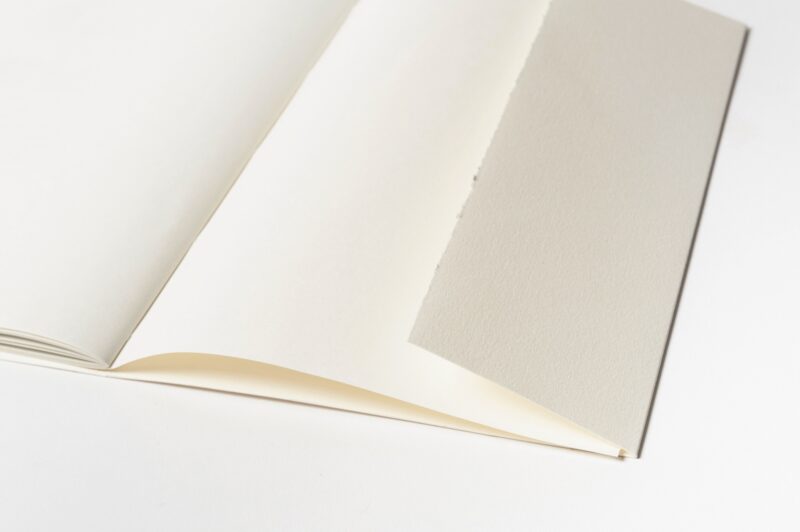

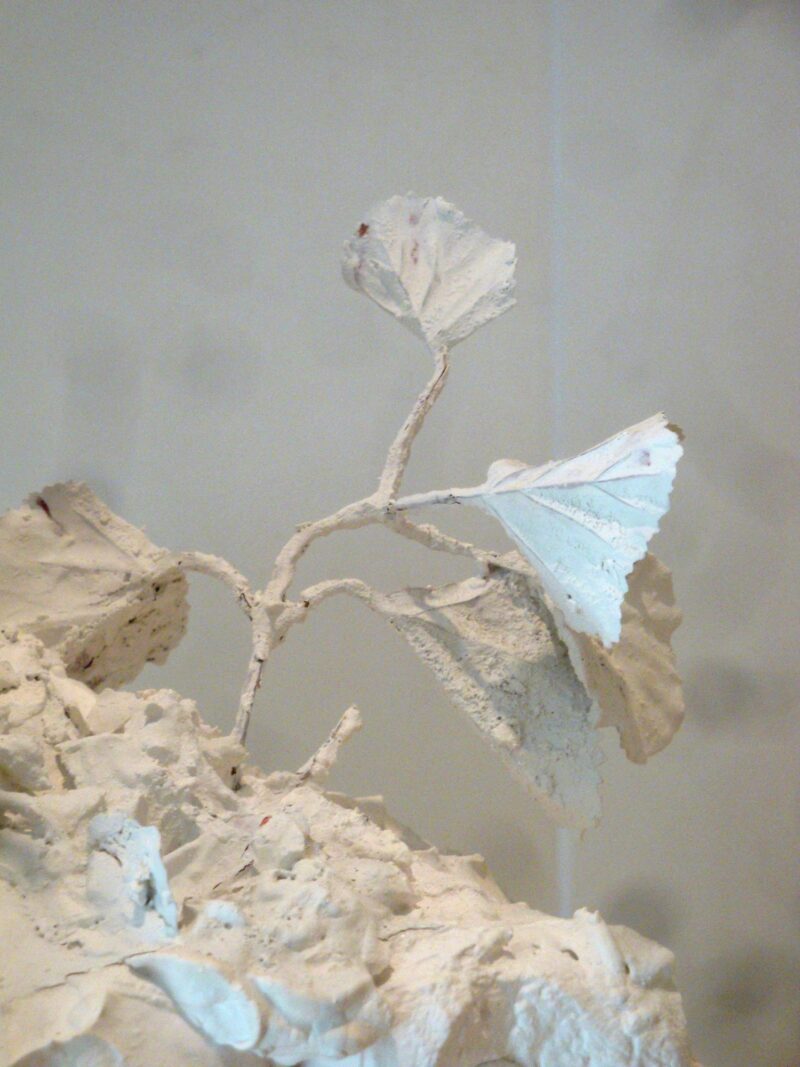

Fournier describes his relationship with Zebrowski as one of friendship and ideas: a process of consultation between two artists. After their first collaboration in 2002, they went on to make fourteen books together, and Zebrowski has always credited Fournier’s work in her colophons. In a sense, the apotheosis of their joint adventure was the creation of Open Book/The White Book (2009) – a massive, blank, all-white, 712-page book made with thick Arches paper by Papeterie Saint-Armand and an intricate French cross-stitch binding. Zebrowski characterizes the work as a “paper sculpture,” and though it has not yet been exhibited, it can be considered the most radical outcome of her ongoing conceptual exploration of the book form. In the absence of images or text to command our attention, we are left solely with the physical presence of paper and thread.

In 2006, Fournier introduced Zebrowski to artist Francine Savard, whose own works have been exhibited at such institutions as the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, Diaz Contemporary, the Vancouver Art Gallery, and Galerie René Blouin (now Blouin Division). In addition to maintaining her own practice as a painter who explores the history of abstract painting with intention and rigour, Savard has for many years worked as a graphic designer. Fifteen years and over fifteen books later, Zebrowski says that her links with Savard are those of friendship and active collaboration. Among the qualities that Savard brings to the table as a graphic designer, Zebrowski mentions her sense of scale, her visual sensitivity, and her delicate and poetic layout of text. In fact, it is not difficult to see that certain elements of Savard’s own practice – for instance, a precise and meaningful use of language and a refined yet impactful synthesis of colour and form – also emerge in her graphic design. Yet for her, collaboration with another artist is a process in which she must be ever conscious of not overstepping bounds. In contrast to the catalogue design contracts that she regularly undertakes for institutions such as the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal and the Musée national des beaux-arts du Québec, which usually leave her free to propose a strong graphic concept, Savard believes that her role in making other artists’ books is to aid rather than direct the creative process. Her method is to make many suggestions and to remain sensitive to the artist’s particular vision.

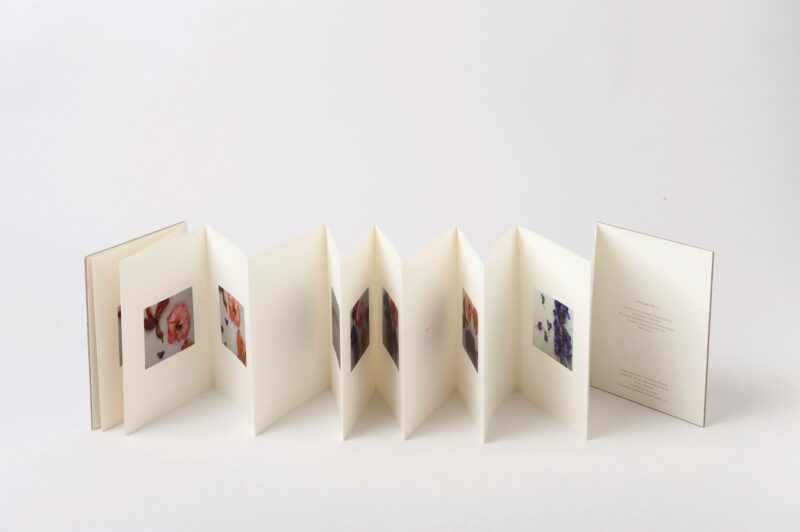

Savard’s work with Zebrowski seems to me to focus on achieving the greatest overall effect through the very subtlest of graphic means. A good example is one of their latest collaborations, I Never Knew Cy Twombly (2020), which features a series of twenty poems by Zebrowski (and only a single photograph, not by her) on her recent intellectual and emotional pilgrimages into the work of painter, sculptor, and photographer Cy Twombly. The entire emphasis of the book is on printed words, yet they appear to merely whisper, floating calmly in the centre of each page. The success of such a delicate work is also clearly due to the expertise of the printer, which Zebrowski identifies as another key collaborator that must understand the spirit of the work in order to deliver a beautiful object. For many years, she used the services of Montreal workshop PhotoSynthèse, but since 2015 her books have been made by Datz Press, a publisher based in Seoul.

Zebrowski has long been aware of the vital role that words can play in an artist’s book, and, in addition to writing herself, she has frequently worked with authors and poets, among them Mark Strand, Pascale Quiviger, and Theodore K. Rabb. She also has an ongoing working relationship with poet and novelist Anne Michaels, who contributed texts to Zebrowski’s van gogh’s bed (2020), For Mark (2015), and Sea of Lanterns (2011). With Michaels and other authors, the collaborative process is slightly less interactive, in the sense that Zebrowski accepts without question the texts that the author sends her. Nevertheless, once the book’s design is nearing completion, the authors are given the chance to review the visual placement of their words – and thus also have a hand in the work’s graphic outcome. This last detail may come as a surprise to some writers, but it is entirely in line with Zebrowski’s commitment to collaboration.

The fact is, Zebrowski is never truly alone. In my view, the very subjects of her books reflect the degree of her involvement with other creative people. Several of her works – starting with her “circle of poets” trilogy, and followed by her books on artists Andrew Wyeth (Finding Wyeth, 2012; at the window, 2018), Vincent van Gogh (van gogh’s bed, 2020), and Cy Twombly (twombly, italia, 2015; a bouquet for Cy, 2017; The White Sculptures, 2019; I Never Knew Cy Twombly, 2020) – have been devoted to what may be described as the enduring physical and affective impact that visual and literary artists have had on the world. She is broadly interested in the subtle traces left by history and lives lived in both interior spaces and landscapes, but it is not by chance that artists have featured heavily in her photographic exploration of such traces. Wyeth, Van Gogh, and Twombly have, in a sense, also been part of her collaborative process, for – just as she has welcomed the creative participation of Fournier, Savard, and others – she has given them a space to exist in her work. The depth of her engagement with Twombly in particular (whom, as one of her titles explicitly states, she never met) seems to have made their connection equivalent to her in-person relationships.

So, what of the notion of the author, considered at the outset? Does it provoke a sense of discomfort to insist, as I have here, that the act of making Zebrowski’s books is a shared endeavour? Does the fact of bringing other individuals into the discussion and giving them a degree of artistic agency diminish her own authority? If it does, it surely reveals how deep the notion of the singular creative genius lies in our conception of art-making. But deeply embedded doesn’t mean appropriate, and the genius of Zebrowski’s art is that it helps us open up to the alternative notion: that artistic creation is something that happens between people. The task of the art historian or critic then becomes to ask how, rather than what – not: what is this about? but: how do these people make this together? It is certainly a challenge, because dealing with people can be messy. But, as Zebrowski clearly demonstrates, it can also be extremely fruitful.

Zoë Tousignant is a photography historian and curator based in Montreal. She has worked on several book projects, including Gabor Szilasi: The Art World in Montreal, 1960–1980 (Montreal: McCord Museum and McGill-Queen’s University Press, 2019), and Serge Clément: Archipel (Montreal and Paris: Occurrence and Éditions Loco, 2018).