[Winter 2021]

By Bruno Chalifour

After months of a world pandemic, being surrounded by clouds may sound like a reprieve: fluffy, light, ethereal, and flying higher than the contemporary political discourse in the United States, clouds may provide temporary solace in our dark, sometimes ignorant, times. The exhibition Gathering Clouds, Photographs from the Nineteenth Century and Today at the George Eastman Museum1 (GEM) proposes such a pause. Programmed before we ever heard of COVID-19, it is set in the museum’s two major galleries and in a smaller third one entirely dedicated to a twenty-seven-minute video loop of contemporary clouds by Berndnaut Smilde. Gathering Clouds, as its subtitle, Photographs from the Nineteenth Century and Today, implies, is divided into two distinct sections. Each one occupies its own gallery. The first deals with how photographers solved the technical issue of rendering clouds over a landscape in the nineteenth century; the orthochromatic nature of the medium did not allow a single correct exposure for both subjects (ground and sky), and photographers were often forced to expose two separate plates (one for the ground and one for the sky) and combine them in the darkroom into one print. The process allowed more control over the final image than masking the sky while exposing the ground. Sometimes photographers, many of whom had been trained as painters, simply drew or painted the clouds in. After a historical, well-illustrated, and educational first section, the second main gallery displays a core of twenty-four Equivalents (photographs of cloudy skies taken by Alfred Stieglitz from the mid-1920s to the mid-1930s as expressions of his psyche) surrounded by a compilation of works by contemporary artists. By comparison with the first section, this latter display seems meant more for entertainment than education, although it is not without a few aesthetic rewards.

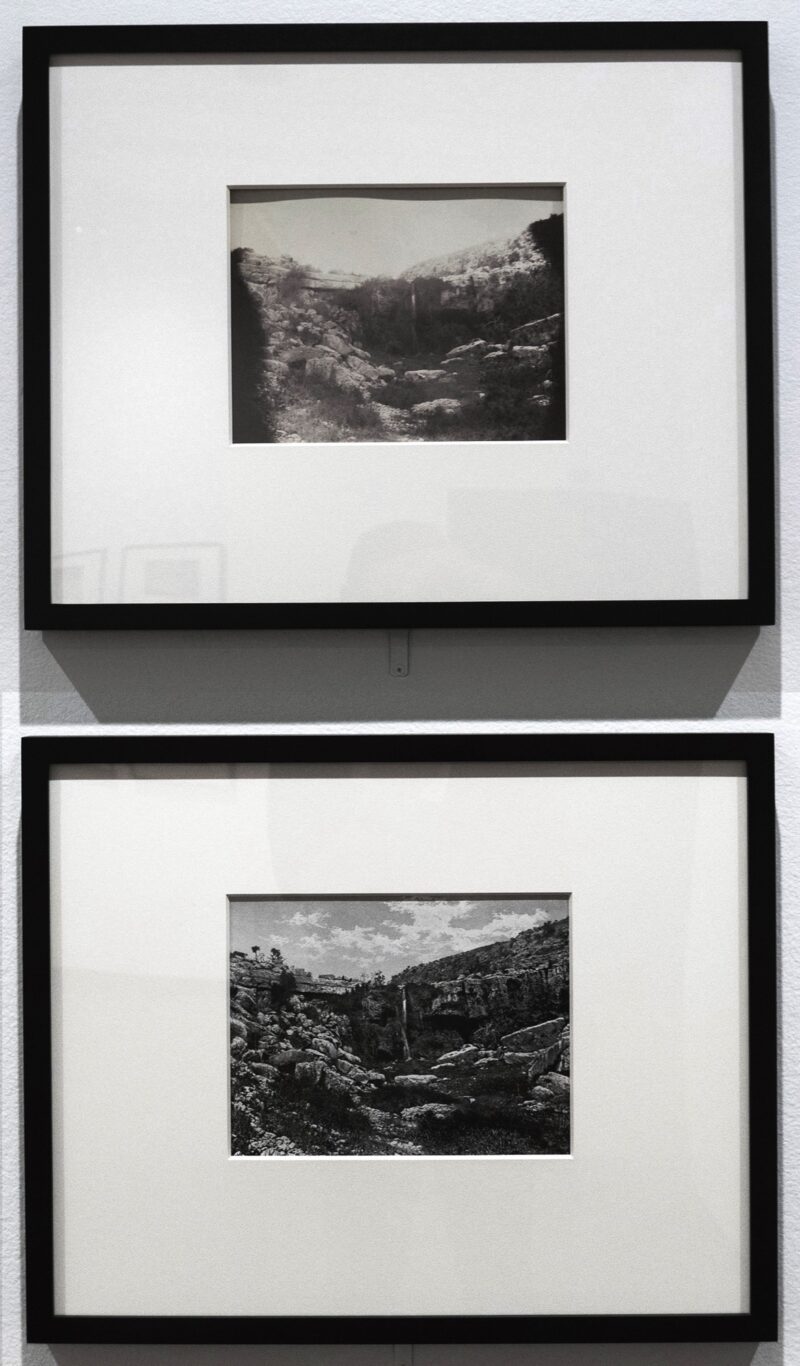

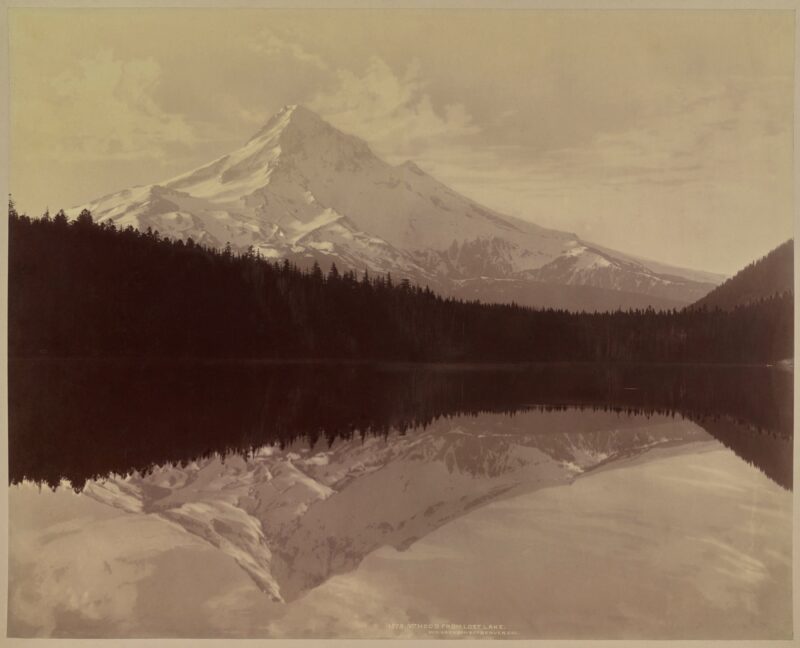

Gallery 1: “Photographs from the Nineteenth Century.” The curator of the exhibition, Heather Shannon, is a specialist in nineteenth-century American photography (the subject of her doctoral dissertation in 2017). Except for an introductory fifty-four-minute video by Penelope Umbrico of 218 details of skies cropped out of nineteenth-century prints (with all their grain and scratches) from the GEM’s collection, all works shown in the first gallery are historical photographs by the likes of Muybridge, Watkins, Jackson, Vroman, Bourne, P. H. Hillers, Emerson, and H. P. Robinson, most drawn from the museum’s rich archive. A few prints have been lent by collectors, including Aïn Mousa, au pied du Mont Nebo (1864) by Louis Vignes, a former student of Charles Nègre, who made the adjoining photogravure created from the photograph. This section also reveals some unexpected jewels, such as William Henry Jackson’s sumptuous 1890 print Mount Hood from Frost Lake, on which Jackson painted in the clouds in the sky and on the surface of the lake. The photographs on display, most of which feed the art market, are accompanied by two documentary pieces: first, a short and very didactic video of Mark Osterman (a world expert on old photographic processes at the GEM) making two separate collodion negatives of a view of the Genesee river in Rochester (the High Falls and the sky above them) and combining them into one albumen print; second, fourteen diptychs of chromolithographs from the 1896 International Cloud Atlas.

Slightly encroaching upon the next century are a number of prints (platinum, gum bichromate, carbon, and other techniques) by pictorialists such as Anne Brigman, Gertrude Käsebier, and Alvin Langdon Coburn. Finally, probably because of its cuteness – a term that can sometimes be at war with relevance and focus – an album compiled by Jacques Henri Lartigue when he was a teenager (Paris, aviation 1910) has found its way into this section. The display is composed of two pages featuring eight very small views of a very small half-distinct biplane against a bland, sometimes lightly cloudy sky.

Gallery 2: “Photographs from Today.” As was the case in Gallery 1, a wide-screen monitor greets the visitor at the entrance to the gallery; this one displays an enlarged landscape by Alfred Stieglitz, On Lake Thun, 1896. This digital and enlarged reproduction (was it necessary – or ethical?) bridges the two galleries and introduces the twenty-four four-by-five-inch contact prints of Stieglitz’s Equivalents occupying the centre of the room. Stieglitz created these rather dark prints as metaphors. They have now become historical icons and inspired later works by Edward Weston, Walter Chappell, Minor White, Carl Chiarenza (who will receive a retrospective at the GEM in 2021), Paul Caponigro, Jerry Uelsmann, and the early Nathan Lyons – all of whom, closely connected with the museum and its archive, are not included in the exhibition. Around the contact prints, Shannon selected a variety of works by contemporary photographers dealing with clouds (sometimes loosely). Contrasting with Stieglitz’s coherent (in subject, intent, and form) body of work, the rest of the works exhibited in the gallery present a confusing, if not confused, hodgepodge.

In this section, two seasoned masters stand out amidst a constellation of either light and entertaining or seemingly pretentious pieces (pretentious at least by their sizes, which express their makers’ intentions and ambitions, but perhaps not matched by the importance of their content). Both Vik Muniz (Reclining Girl and Dog Cloud—Equivalent series, 1993) and Abelardo Morell (Rapidly Moving Clouds Over Field (after Constable), Flatford, England, 2017) display long-established styles characterized by their mastery of the medium, which allows them to elegantly add layers of meaningful, aesthetic, and humorous play.

The Life of a Cloud, April 26, 1:38–2:30 p.m.(2003) and Phantom Skies and Shifty Ground from Eduardo Santiago Muybridge’s Post-Murder Travels (2016), two pieces by Byron Wolfe – who is to Mark Klett what Dr. Watson is to Sherlock Holmes – offer a similar playfulness, but at the level of a student aspiring to a BFA. The Life of a Cloud is cute, and the potential earnestness of the second piece is somewhat eclipsed by a laborious pseudo-scholarly and ironic title, which is a typical trap into which many a student has fallen. The same feeling of “I succumbed to a cute idea” emanates from the ten contact-printed cell-phone photographs of clouds by Nick Marshall (the manager of exhibitions and programs at the GEM since 2013, Marshall holds an MFA from the Rochester Institute of Technology): the prints, the size of a cell-phone screen, display a playful and witty take on Stieglitz’s Equivalents, and this may have oriented Shannon’s choice.

As noted above, the length of a title may actually give away the potential content and facture of a particular work as well as its playful nature. However, what strong piece needs a long title? Long titles often feel as contrived and detrimental to the piece as an overworked frame (also present in this gallery). Cartier-Bresson, Kertész, Koudelka, Robert Frank, E. Weston, Eggleston, Harry Callahan, Larry Sultan, Paul Seawright, Michael Kenna, Luigi Ghirri, Robert Adams, Ed Burtynsky, and Robert Polidori, all celebrated master photographers, have relied on the content of their images first, and used very short, if not laconic, titles for their works, strictly avoiding witty ones. The titles Chez Mondrian and Meudon, 1928 are just peripheral indications that do not overshadow the simple but extraordinary content of two of Kertész’s most famous photographs. Sharon Harper’s Moonfall (As Imagined by the Off-Duty Ferryman Charon in Flight Over the River Styx) (2001), prosaically deals with views of clouds photographed through the window of a plane. The nineteen framed photographs constituting this piece occupy an entire half of a wall of the gallery, “an illustration of the first law of thermodynamics.”

As an interesting addition to a conversation on the nature of titles, Trevor Plagen’s Untitled (Predator Drone) (2010) oscillates between colour-field painting and symphony (it is almost Wagnerian). As in many conceptual and postmodern pieces, the subtitle following Untitled brings a supposedly unwanted-but-intended political bias to the experience of the wall-size work – a meaning that the spectator would have been hard-pressed to decipher if the piece had truly been untitled.

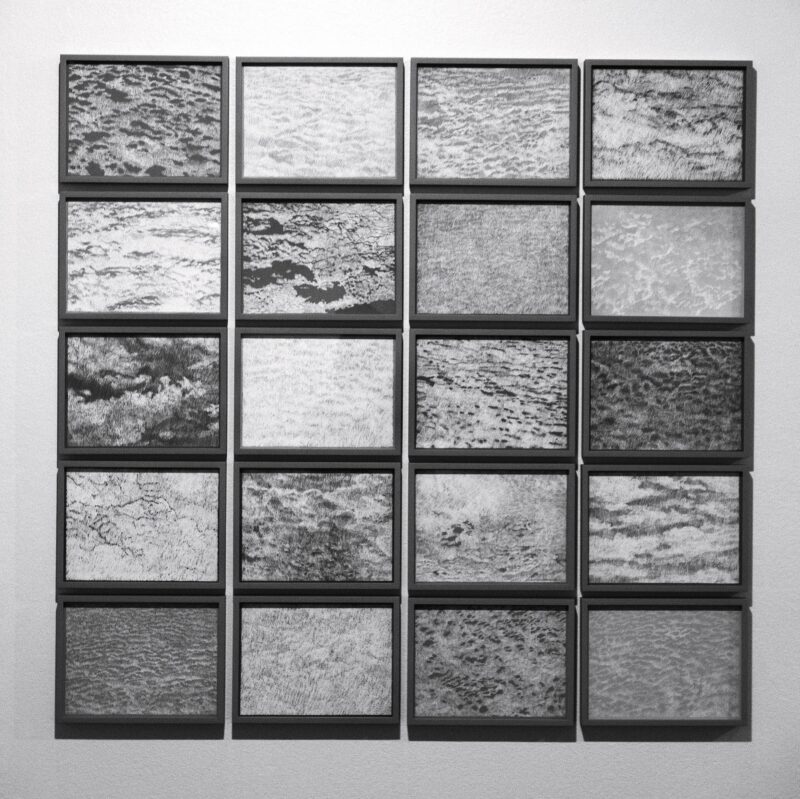

What can be said about Alejandro Cartagena’s accumulation of 191 almost (if not utterly) identical ten-by-fifteen-centimetre chromogenic prints in another bland wall-size piece? His previous successful documentary work, associating content and aesthetic preoccupations, was far more creative. If there are any slight differences between the photographs in the exhibited piece (as should be expected of images taken of a sky looking north, east, south, and west, as the procedure described by Cartagena would have us believe), they do not show at all. As for the form of the piece (a multitude of small photographs arranged in a rectangle), it has been used so many times that it has become trite, especially when it does not seem to add anything to the content of the piece except some pseudo-conceptual format.

Conceptual art may originate from an interesting idea, but cute (such as a reference to conceptualism here) may not be enough to qualify a piece for the wall of an art gallery or museum. To be fair, exhibiting such pieces requires decisions that are not just their authors’. Beyond its content, the title, delivery, facture, and physicality of a piece matter if one chooses to exhibit it. Another wall-size piece by John Chiara shows a single chromogenic photograph of a cloudy sky. It purportedly “wrestle[s] with two uncontrollable variables, the clouds and the photographic process itself.” So? Does that qualify a piece, an artist, for an exhibition? Isn’t an artist (someone whose work is lent by an art gallery, as is the case here) supposed to have mastered his or her craft to better express himself or herself and communicate with an audience? The presentation of Chiara’s piece does not help: the floating print adheres here and there to the glass, the victim of a framing process that did not take into account the potential humidity and the risk that the undulating print might to stick to the pane.

Meanwhile, an example of work whose large size is justified is the panoramic black-and-white composite Air 1 (from the series Auto Immune Response) in which Navajo artist Will Wilson develops a narrative about “the relationship between a Navajo man and a devastatingly beautiful but toxic environment.” Form, including format, meets content there: the self-portrait of the artist, at the far right side of the panorama, physically and metaphorically looks back upon a flooded landscape. Clouds and their reflections on water constitute the vast background of a portrait that tries to reconcile air, water, and light with human presence and activities. The only noticeable flaw is that the final print (because of its size) went beyond what the original resolution of the digital files permitted.

Going clockwise around the room, one ends the visit with two groups of works by Penelope Umbrico and James Tylor. Umbrico uses photographs of clouds on her digital tablet as a drawing pattern on which she draws with a digital pen, filling in the negative space of the original image. The result is twenty poetic and elegant (20 × 25 cm) prints that make original and creative use of new technologies. Tylor, a Kaurna-Maori artist, paints traditional patterns and symbols on top of four traditional black-and-white landscapes, making two cultures collide and creating an interesting tension, echoing issues of identity not just in Australia but in a globalized world.

The first part of Gathering Clouds aptly and elegantly reflects its curator’s field of expertise and the richness of the museum’s archives. It efficiently illustrates the educational potential and mission of a museum: educational and subtly entertaining. The second part, except for Stieglitz’s Equivalents, is more tentative in intent and content. It seems to fall prey to the merely entertaining aspect of a show resulting from superficial expertise and research. One can only deplore that the depth, intelligence, and coherence of the first gallery was not matched in the second one. The choices made for the second part of Gathering Clouds – in which the pun takes on its full meaning –may have been justified by a desire to show diversity and expose the audience to some potentially entertaining new works. Expertise versus entertainment – this may be simply a rearguard struggle, a survival reflex on my part, in a world in which spectacle and inflated platitudes (many born out of ignorance and laziness) are inflicted upon us daily through “social” media. I understand that I do not represent the average visitor, but I believe in the educational mission of museums. In an era in which so many TV and social media channels cater to and encourage a short attention span, a desire for spectacular and often superficial entertainment, museums remain the breath of oxygen that our brains desperately need, offering thoughtful analysis and expertise, considering history and human creations while providing aesthetic education and pleasure; Gathering Clouds got halfway there.

1 Gathering Clouds was held from July 26, 2020, to January 3, 2021 at the George Eastman Museum, Rochester, NY, and was curated by Heather Shannon, associate curator at the GEM.

Bruno Chalifour is a photographer who has been teaching and writing about photography for more than forty years. He moved to Rochester, New York, in 1994 and was editor-in-chief of the magazine Afterimage (2002–05) and director of Light Impressions/Spectrum Gallery (2014–15). In 2019, he defended his doctoral dissertation on American photography at Université-Lumière Lyon 2 (France). His writings have been published in France, Australia, Canada, the United Kingdom, and the United States, and his images have been in numerous solo and group exhibitions in France and the United States.