[Summer 2021]

Correspondence and Adventures in Book Form

By Jérôme Delgado

From the traditional exchange of letters to dialogue that’s more indirect, correspondence takes various forms, especially when, through words – or simply instead of them – photography is the object of the discussion. With its narrative nature, its poetic range, its multiple paths of reading, an image in itself is speech that leads to other speech. It occurred to me to bring together three photo-books published in 2020, each of which is a true adventure.

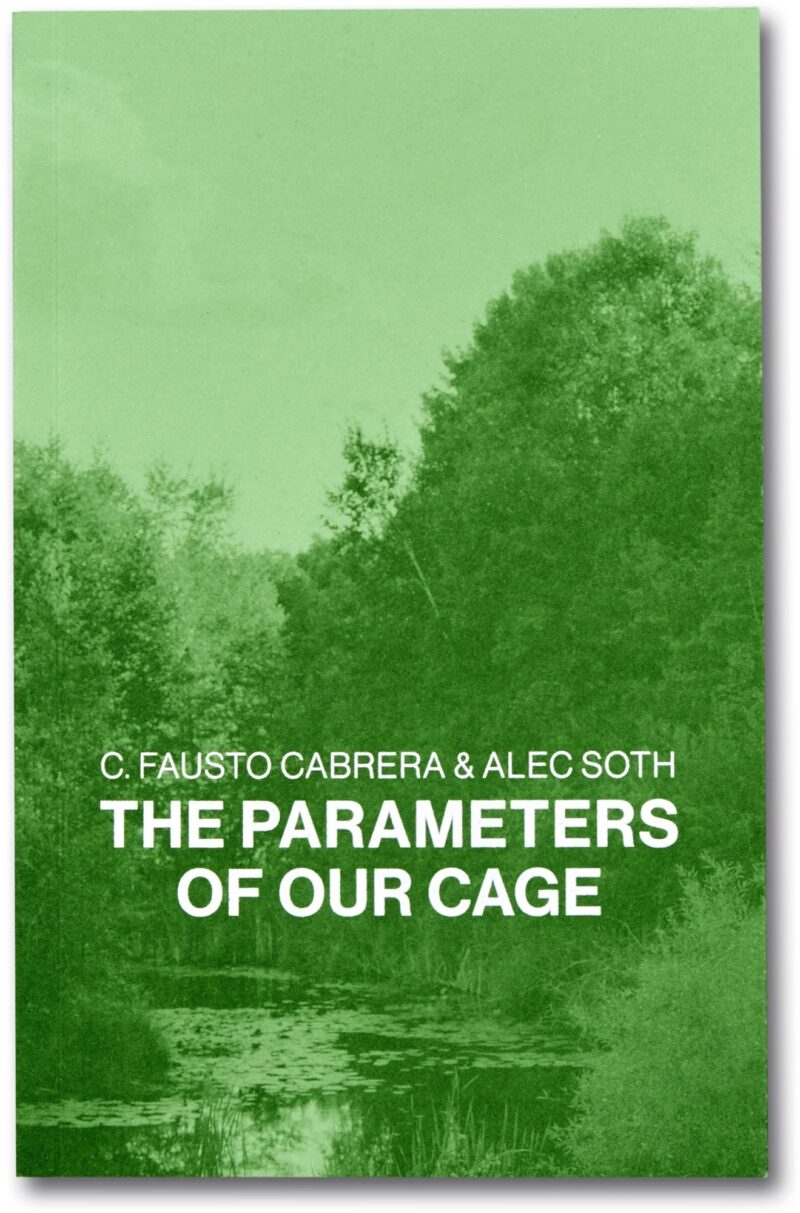

The first, The Parameters of Our Cage,1 is a classic example of written correspondence. Please forgive this little detour! It goes without saying that this publication, which pairs Alec Soth, a photographer from Minnesota and member of the Magnum agency, with C. Fausto Cabrera, incarcerated in a Minnesota prison, doesn’t fit the usual definition of a photobook. And yet, the photograph – the image, or the result, and its concept upstream – is at the heart of the exchange, as if it were a watermark underlying each missive.

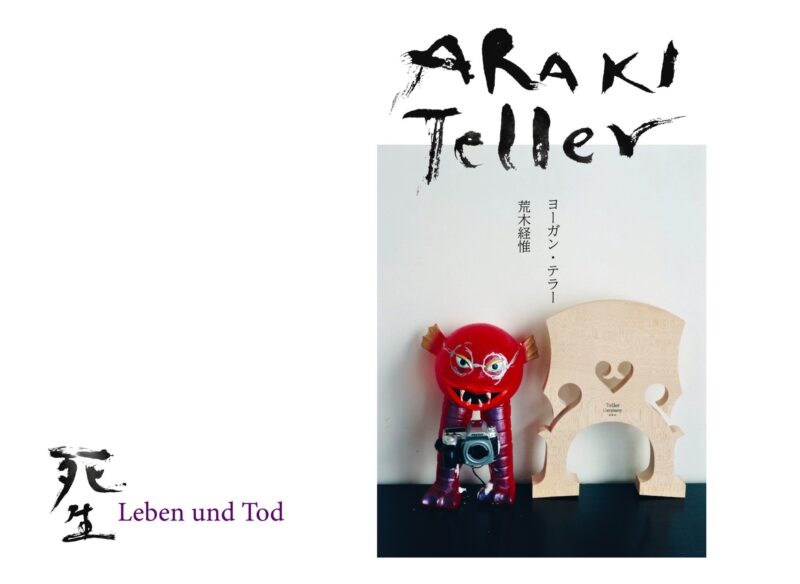

The opposite case is an entirely photographic book, Leben und Tod2 – life and death – which contains an interchange of pictures between two photographers known for their acerbic, unfiltered practices: Juergen Teller from Germany and Nobuyoshi Araki from Japan. It is not the first time the two have collaborated on a book. Leben und Tod was built on exchanges (of objects and images), geographic distance, and the passage of time – as it happens, a correspondence.

The final case is another essentially photographic project, The Illusion of an Everlasting Summer.3 This book by Alessandra Sanguinetti, a photographer living in California, departs from correspondence as we usually think of it. No letters or images were actually sent. Instead, Sanguinetti travelled over the years, repeatedly, in order to meet up with her “correspondents,” Guille and Belinda, in rural Argentina. The exchange is solely photographic. That is, the resulting images, which compose this book (and a preceding volume4), would not exist had the communication been in one direction only.

For Soth, who previously produced the book Sleeping by the Mississippi (2004), photographic practice facilitates connections, including with oneself. “I use other people’s lives to learn about my own,” he writes to his correspondent. “I often say that when I take a portrait, the thing I’m really capturing is the space between myself and my subject. If I’m a connoisseur of anything, it’s social distance.”

It is perhaps not by chance that Cabrera, in his desire to reach out beyond his prison cell, wrote to Soth. After all, Soth is a man of words. A book that he recently published (I Know How Furiously Your Heart is Beating, 2019) concluded with an interview with novelist Hanya Yanagihara. His fascination with oral communication is also manifested on YouTube. The initial request by Cabrera, who introduced himself as a writer and artist, did not fall on deaf ears: Soth revealed himself to be not only an available correspondent but a good advisor and an insatiable motivator.

Although COVID-19 and the Black Lives Matter movement colour their exchanges, which involve issues such as freedom of movement, violence, and the right to rehabilitation, photography is never far away. Often it is explicit, as when Soth confides that he has learned to “photograph the energy” that is emitted when he meets an individual – an admission that speaks in favour of photography that goes beyond the recorded image. In The Parameters of our Cage, it is concretely conveyed. The image printed on the front and back covers reproduces a detail of a photograph taken in August 2020, seven months after the correspondence began. It portrays an outdoor get-together, with sky and trees predominating in a composition proper to the romantic landscape.

The full version of this photograph and a second one – a close shot of the guests – are the outcome of the book, a conclusion so vast that it doesn’t fit within its pages. Produced by Soth as he thought of his now-friend Fausto (known as Chris to his close friends), the two images are printed on thick stock as postcards. Titled Picture for Chris, they suggest that the correspondence continues beyond the parameters of the publication.

Picture for Chris #1 concerns more than an outdoor scene. The landscape evokes the man who stayed in prison, his imaginary, his dream of an image. Soth had asked him at one point to describe eight photographs that he would take with him to a desert island. One of them, taken on a summer day at a friends’ farm, would “capture the scope of the place while everyone is outside.” Taken from a slight high angle, the general shot that Soth takes from Fausto’s description expresses just as much, if not more, the friendship – or energy – between the two men, who are missing from the image and yet essential to its composition.

A similar understated presence permeates The Adventures of Guille and Belinda and The Illusion of an Everlasting Summer. The cover image bears a trace of the photographer, Sanguinetti, and the narrative upon which the book draws. The two cousins at the heart of this epic photographic project (begun in 1999, it is still ongoing) are sitting on a bed facing the camera, their gaze pensive rather than attentive. One of the photographs on the wall behind them is partially obscured by reflected light. Daylight or not, it stands in for a third figure, central to the composition and embodied by Sanguinetti – she’s the one who “writes” the light.

The entire project is encapsulated in this image: the theme of the gaze, between the dreamy poses of the subjects and the subtle presence of the artist, the references to the countryside and animals (present in another photograph on the wall, as toys, and in the bedspread), and the inevitable passage of the years, signalled by the portrait of a little girl hanging on the wall. Even as the book describes the growing up of Guille and Belinda – kids in the first pages, mothers in the last – it abounds with details on the construction, in images, of a life.

The pleasure of play is palpable in the pictures, from one of the cousins buried in the ground with only their heads sticking out to those that theatricalize everyday scenes, including when one of them is swept off her feet by love. The cousins’ trust in the photographer, and vice versa, is such that there is no modesty or favouritism or position of authority. The “stagings” are decided collegially. Without this – without the sum of their energy – there would be neither adventures nor book(s).

One moment in reality, the next in the imaginary. In the book, illusion is vitally important. The photograph of the two girls looking at themselves in the water is not flipped for nothing – the reflection on top, the reality on the bottom. Even in their absence, Sanguinetti captures instants worthy of a well-constructed fable. For instance, in a composition marked by the crossing of two diagonals are a clock, an enchanting painting, and a hand feeding a baby bird. Time, fantasy, and daily life in a single shot: it makes all the sense in the world.

Daily life. If Juergen Teller and Araki Nobuyoshi share one thing, it’s an assumed and instinctive penchant for photographing life as it parades before their eyes. Known for his fashion photography, Teller has a career outside of these commissions, in which he often features himself. Nobuyoshi, from the world of advertising, is a venerable figure of auteur photography in Japan, whose early career in the 1970s featured images of his marriage and honeymoon. Portraits, nudes, and sexuality, as well as objects, flowers, and various metaphoric structures, are other subjects that they share.

The title that brought them together a second time doesn’t have the prestige of their previous book, Araki Teller, Teller Araki (2014). Less ambitious, it doesn’t interlay one’s black-and-white images with the other’s colour images. Now, the interchange takes place, so to speak, before printing.

Life and death go together for Araki, who apparently “designed his work as projection of the future.” Although, at almost eighty years of age, he has lost physical mobility and the vision in one eye, the prolific photographer and author of more than five hundred (!) books9, has no plans to stop. He was the instigator of Leben und Tod: he asked Teller to send him objects from his childhood so he could photograph them. Along with stuffed toys and figurines, violin music stands made in the family factory made the trip.

The book creates a dialogue between the images that Araki created in this context and those that Teller made in parallel. The contrast is inarguable between the former – theatres of objects that betray the immobility of their author – and the latter, a variety of shots taken outside the home (from the forest to the gym, and even traces of a recent trip to Bhutan). But the contagion is reciprocal, as if the energy that Soth talks about had crossed continents.

These three books share neither their processes nor their results. Side by side, the differences are obvious. Soth and Cabrera’s, pocket-sized, can be held in one hand. Araki and Teller’s, barely larger, is in a horizontal format. Sanguinetti’s Guille and Belinda, square in shape, is the largest in size. And yet, they have more than one thing in common. Born from affection between individuals, culturally or socially distant at first, and physically separated – if not by thousands of kilometres then by walls – these books radiate humanity, page after page, image after image. As our planet succumbs to the effects of the virus, leading us to avoid strangers (outside our bubble), such offerings give hope. Photography is not a cure, but, at least in these books, it keeps the dialogue going, encourages us to grow closer, or, to paraphrase one of the three titles, to make summer (of our dreams) everlasting. Translated by Käthe Roth

1 C. Fausto Cabrera et Alec Soth, The Parameters of Our Cage, Londres, MAKP, 2020, 128 p.

2 2 Nobuyoshi Araki, Juergen Teller, Leben und Tod, Göttingen, Steidl, 2020, 72 pages, 67 images.

2 3 Alessandra Sanguinetti, The Adventures of Guille and Belinda and The Illusion of an Everlasting Summer, Londres, MAKP, 2020, 164 p.

2 4 Alessandra Sanguinetti, The Adventures of Guille and Belinda and The Enigmatic Meaning of their Dreams, Portland, Nazraeli Press, 2010, 120 p. Réédité en 2021 à Londres, par MAKP.

2 5 Cabrera and Soth, The Parameters, p. 51

2 6 Cabrera and Soth, The Parameters, p. 26

2 7 Cabrera and Soth, The Parameters, p. 19

2 8 Jérôme Neutres (dir.), Araki Nobuyoshi, Paris, Gallimard, Musée national des arts asiatiques – Guimet, 2016, 304 p.

2 9 Idem.

Jérôme Delgado is a freelance journalist who publishes cultural reports and reviews in the daily Le Devoir and the film magazine Séquences. Since March 2020, he has been the publishing coordinator at Ciel variable.

[ See the magazine for the complete article and more images : Ciel variable 117 – SHIFTED ]