[Summer 2021]

A story, July 13, 1999, to the present (excerpts)

Franck Gérard

A press clipping. A few months after my fall, a patron, Löic Francheteau from Flesselles, in a bar where I hang out showed me a newspaper clipping that he had cut out for me. The article tells the story of a young woman who hadn’t had my good luck: a neighbour found her lifeless in the morning. She had fallen in the elevator cage, from the second floor; she had died of a cerebral hemorrhage. I didn’t get much of a laugh out of it . . .

I’m a survivor who really should have been part of the famous “Forever 27 Club,” except that my death would have gone completely unnoticed. Yes, when I fell, I was twenty-seven years old, as I’ve mentioned. On the other hand, I find this delicious chance to die laughing . . . we should found a “Survivors 27 Club,” shouldn’t we?

Seeing. I get the feeling that everyone sees what I see, but obviously our point of view depends only on ourselves. That is, everything we’ve assimilated since we were very young has constructed our relationship with the world.

One day that same year, I had an appointment at a company that sells all sorts of lawn products. When I arrived at reception, I sat down facing a large black-and-white poster that covered the entire wall: it was a photograph of a man mowing a huge lawn with a little tractor. I noticed a pretty funny detail. I asked the lady at reception if I could take a picture. She asked why. So, I explained that it looked like the man mowing the lawn had in front of him, in the foreground, a real plant, which was actually a plant in the office placed there by chance. And suddenly she saw the irony of the situation and burst out laughing. She let me take the picture. Then she thanked me, telling me I’d opened her eyes, because she’d been working there for four years and had never noticed that. It’s a real pleasure to have little moments like that one.

Later, people who’d seen my images regularly told me, “Now I see in a different way, I see like you, I pay more attention to the things around me.”

They’ll also say to me, “I saw a picture you took!” – that is, an image I might have made. I find the idea of making images “by proxy” funny.

I sort of feel like that fall gave me back my vision, or at least the pleasure of looking, of contemplating the world . . .

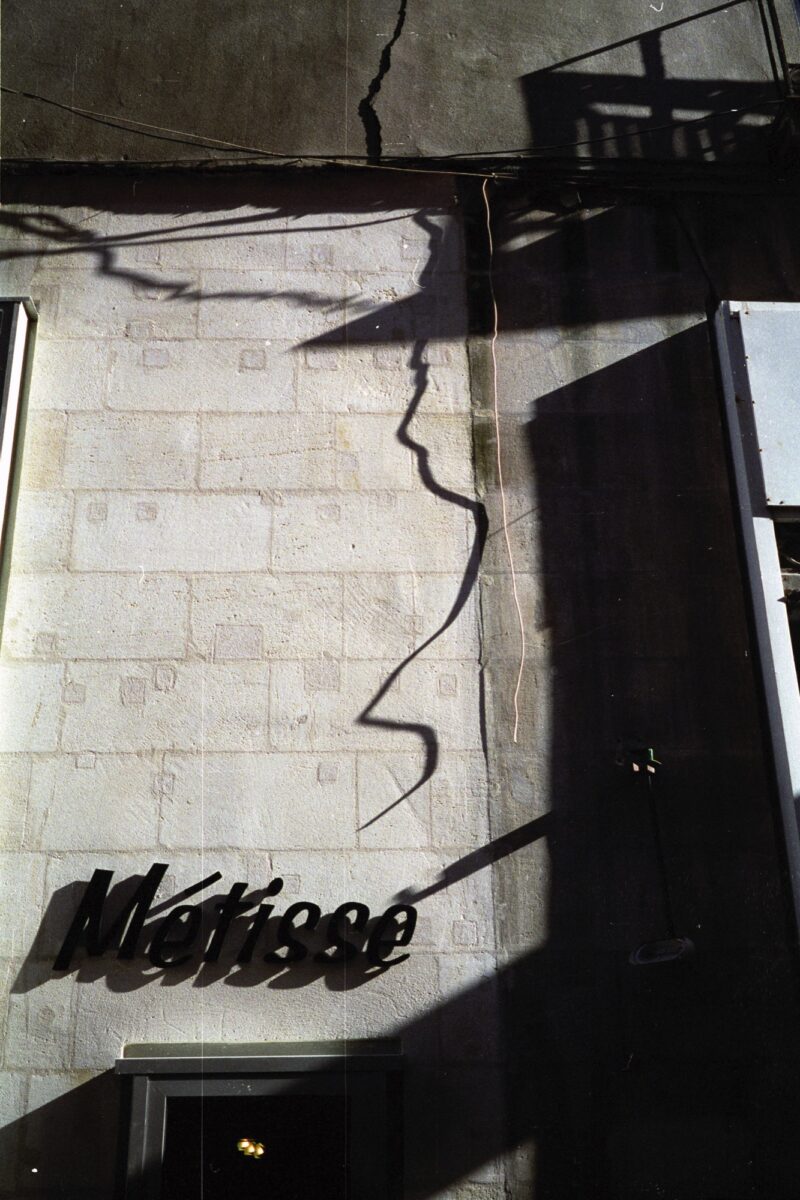

The wire shadow. In general, what’s interesting about a photograph is understanding the photographer’s intention. At the same time, everyone is different, so everyone can uncover part of the truth – at least, his or her own truth – in an image. It’s inherent to photography, what they call interpretation. No one will ever understand certain signs that I’ve placed in my photographs, but they’ll be able to uncover things I can’t see. That’s the game . . . Many anecdotes come out of my images. They’re both photographs and stories, moments from my life and others’ lives.

For example, I’ve often shown this one. I’ve commented that most of the time people can’t see what I “put there,” they can’t grasp it immediately. Usually, I have to explain it. It’s all based on the twisted wire hanging on the right side of the image, which casts a shadow that looks like the silhouette of a private detective right out of a novel by Dashiell Hammett or Ross Macdonald: the outline of the raincoat, the profile of the face, and above is the hat, the shadow of which isn’t related to the wire.

It happened once – the sun was perfect – and it never happened again. The wire disappeared a long time ago: nothing is unchanging, that’s what I also realized. I’m not longer the superhero of my childhood, the one who thought he’d never die. . . . Time passes; all the more reason to capture it when the situation allows me to. How many times has it happened to you that you go by something you want to photograph and you tell yourself it will still be there tomorrow . . . and then one fine morning it’s all gone. Translated by Käthe Roth

Franck Gérard’s Photographic Encounters

By Jacques Leenhardt

“I [the photographer] don’t invent anything. I imagine everything.”

– Brassaï

Containing a “diary” written by Franck Gérard during his wanderings and an avalanche of photographs, En l’état1 is a book that is difficult to classify. This mélange refers to notebooks kept by travellers and characterized by stylistic hybridity. But En l’état also resembles a manifesto, as if Gérard wanted to affirm, by writing and photographing, that he takes himself for neither a writer nor a photographer. Two precarious notions are thus combined here, and Gérard transforms them into a unique and anarchical artistic statement. He is determined, a serious dilettante who would never leave home without his camera. This rule is the consequence of his idea of his art, fully bound within the encounter between the photographer and being-there in the world. He is an outdoor photographer: he strolls around, musing on the coincidences of situations, ever on the look-out. This is his ethic and his poetics. He inhales the urban ambience – which is his true world – seeking out traces left in the city by human lives. As we know, photography never totally escapes the real world, the evidence of which it preserves. And yet, what it shows is only the displaced reflection of this reality, the narrative of a ramble that could be described as dreamlike.

In Gérard’s images, everyday reality is both asserted and fleeting. This is because his imagination – let’s call it photographic work – captures exactly this difference of the real with itself, its separation from itself, its intrinsic strangeness.

In her critique of the surrealistic tendency of photography – which she feels is its essence – Susan Sontag wrote of American photographers that they “are often on the road, overcome with disrespectful wonder at what their country offers in the way of surreal surprises. Moralists and conscienceless despoilers, children and foreigners in their own land, they will get something down that is disappearing.”2 This description coincides quite well with certain aspects of Gérard’s practice. However, he feels no nostalgia with regard to what is disappearing. On the contrary, his photographs capture the sometimes-sardonic humour of life, the form in which our actions and emotions of an instant are fixed in an image, without our suspecting it. There’s no romantic or Benjaminian nostalgia in this offering of life through the photographer’s eye. For him, “shooting” a picture is related to play rather than deadly seriousness; it’s a gesture that pays tribute to his joyous appetite for immortalizing moments of innocence. We might liken Gérard’s work to Raymond Depardon’s, but only if we note a distinct inflection point: although they’re both curious about what we might call people’s lives, Gérard’s images are both less political and more ironic than Dépardon’s. This is no doubt because they belong to different generations of the photographic gaze; already aware of his immersion in the flow of images, Gérard perceives the very fragility of their meaning.

In his view, empathy for the spectacle of the world is never disentangled from an amused or regretful distancing. The images in En l’état expose this slight gap, the echo structure that marks the real in the photograph even as it weakens the political attitude that all images imply. The very title of the book makes this obvious. In En l’état, Gérard warns from the start that it is not his vocation to intervene either on the event that presents itself or on the photographic object that leaves the laboratory. All manipulation would be inappropriate; framing is the only legitimate intervention. Gérard never composes a staging – which sheds light on his dispute with Bernard Faucon – any more than he manipulates his shots or prints. The scene and its image must be reconstructed “as is,” which is their truth. This passionate search for the real does not presuppose, however, an assumed truth of the photographic image – an old myth that has long since been abandoned; on the contrary, it pays tribute to the image’s enduring duplicity, to the echo that redoubles its reflective surface and strikes our imagination. Translated by Käthe Roth

Honorary president of the International Association of Art Critics (AICA), Jacques Leenhardt is director of studies at the École des Hautes Études en Sciences Sociales in Paris. As a curator, he has organized exhibitions with Brazil as the subject, including Arte Frágil, Resistências (2009) and Iberê Camargo, Século XXI (2014). He has also written and edited many books, including Wifredo Lam (2009) and Jean-Baptiste Debret, Voyage pittoresque et historique au Brésil, 1835–1839 (2014).

Franck Gérard, born in Poitiers in 1972, is a “reality hunter” who humorously and kindly tracks the originality of daily life, with a focus on its humanity. A graduate of the École des Beaux-Arts de Nantes, he has presented his work at the Rencontres Internationales de la Photographie d’Arles, Centre Georges Pompidou-Metz, Château des ducs de Bretagne in Nantes, the Lieu Unique, Galerie Mélanie Rio Fluency, the Fondation d’Entreprise Ricard in Paris, FRAC PACA, the Museum of Contemporary Art at the University of Sao Paulo, and the Centre d’art et du paysage de Vassivière in Limousin, as well as in the United Kingdom and Germany. www.franckgerard.eu

[ See the magazine for the complete article and more images : Ciel variable 117 – SHIFTED ]