[Summer 2021]

The Artful Life (according to Vincent Lafrance)

by Zoë Tousignant

It was a time when amateur gourmet cooking and wine tasting triumphed over literary and philosophical knowledge. People read less, but they understood wines. The Robert Parker years were over: young middle-class people were looking for acidity, minerality, and even frizzante.

In my late thirties, I had gradually left the visual arts scene. I had returned to my early training and came around to earning a living as a commercial photographer.

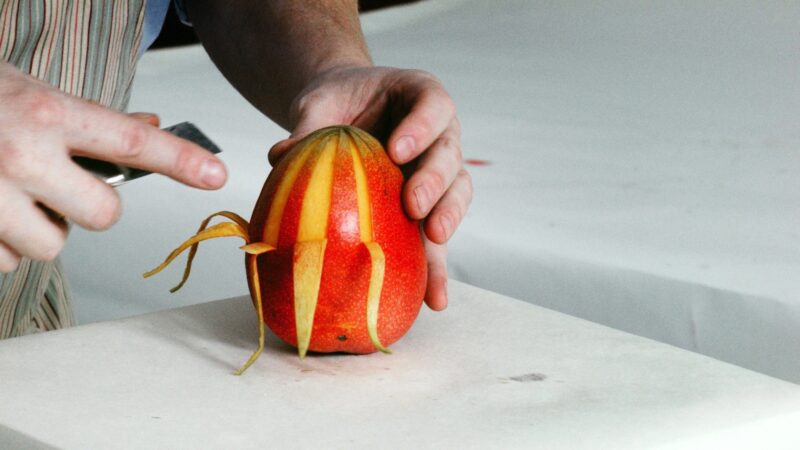

I had become a food photographer, and my professional career was going really well. I had contracts from a bunch of Canadian and international clients. In general, they liked the experimental touches that I added to my work. My specialty was alcoholic beverages.

Choosing fruits or vegetables is like searching for the decisive moment. The first step in a good image is located in the aisles of the grocery store. You have to know how to look, to stay alert. I try never to have preconceived ideas about what I’ll find. I let the displays speak; the images come into my head as I’m walking around with my cart. I love these moments of reverie. It reminds me of my strolls when I was doing street photography.

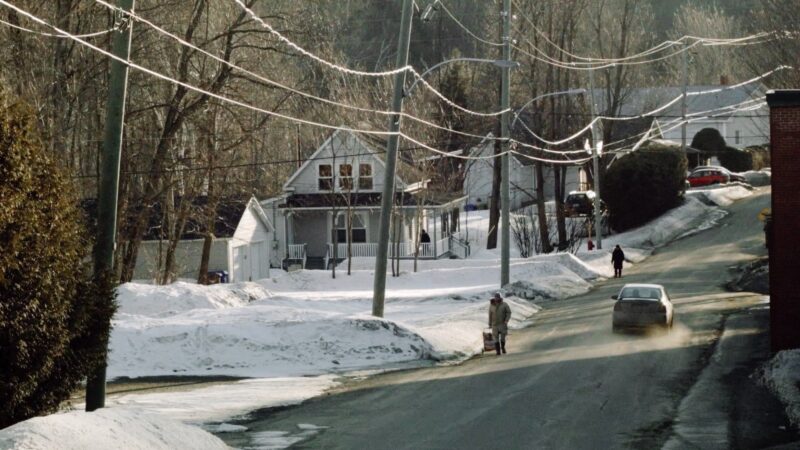

After the winter holidays, a long period of seclusion follows quite naturally. Without television or Internet, I read a bit, I watched the fire, I fell asleep fast. Winter is exhausting. In my life, I learned early that it was possible to experience all the necessary emotions in solitude. Even though I loved, and still love, people, winter necessarily distances us in any case.

I have a nice collection of sabered bottles. I built a corpus of images with them. I particularly liked the appearance of danger in the sliced glass. The presence of insects was, of course, a reference to still life in painting. In contemporary art, the use of references or quotations enabled us to dodge gratuitous gestures.

I used commercial shooting strategies to produce visual art. Of course, the work stayed in the computer. Although I had stopped disseminating my art, I still continued to produce artworks, with no obligations. My breaking away from art was still new, and still painful. I adored being an artist.

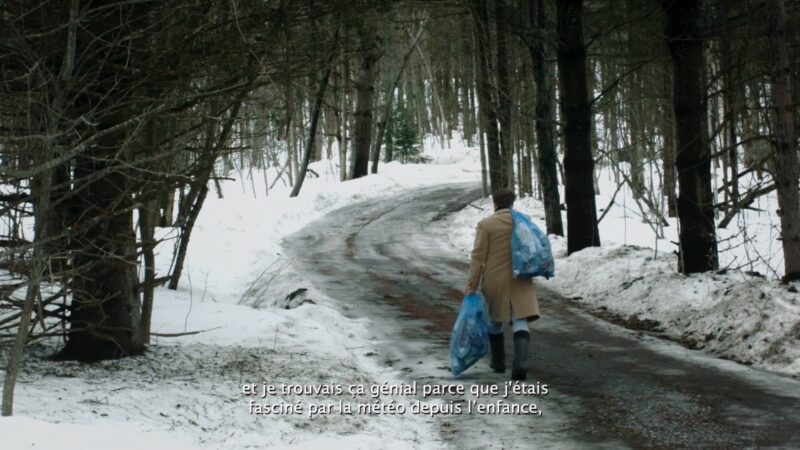

To save time, I often cut through a forest to get to a grocery store in Newport. Entering the United States was illegal, but I avoided ninety minutes of walking. Realizing halfway home from the grocery store that I’d forgotten something essential made me feel horrible.

I didn’t have visitors. I don’t believe I had very close friends at the time. I knew the great solitary heroes. The ones who went wild, like Robinson Crusoe, the thinkers like Thoreau. Between the wood to be cut, the land to be taken care of,and the studio, I never came to wonder about my mood, or about solitude as a position or subject for reflection.

The forecast storm arrived at the announced time. This clairvoyance never ceased to surprise me.

Vincent Lafrance and I first met in 1996, when we were both young students in Cégep du Vieux-Montréal’s photography program. I decided early on that I liked his photographs – so much so that I purchased a selection of small prints that he had made for a class assignment: a series of delicate black-and-white landscapes, printed on fibre paper, of his hometown of Saint-Mathias-sur-Richelieu. I now recognize this acquisitive gesture as an early sign of my eventual withdrawal from the practice of photography in favour of a much more heartfelt theoretical engagement with other people’s images. I also see it as evidence of an intuited aesthetic fellowship. Although I am not always aware of the details of Lafrance’s private life, over the past twenty-five years we have collaborated on a number of projects.1 We share an interest in popular forms of expression, a belief that contemporary art can be accessible to a broad public, and a desire to document, in one way or another, the individuals that make up Quebec’s visual arts community. I feel that I have a grasp of the trajectory of his art career so far, and that I understand his particular brand of humour – and the seriousness with which he applies it.

Lafrance’s most recent video work, Savoir vivre (2021), is a web series composed of twelve short clips, ranging from five to eight minutes each. It tells the story of “Vincent Lafrance,” who, after the death of his father, is tasked with the sale of the family cottage located in Fitch Bay, in the Eastern Townships. He arrives at the house in the middle of winter; over the course of what appear to be several months, we see him contend with the difficulties of getting around in the country without a car (due to the recent loss of his driver’s licence), selling a cottage in the dead of winter, and maintaining his work as a professional – albeit rather eccentric – culinary photographer. With only a few exceptions, “Vincent Lafrance” is seen utterly alone, endlessly clearing the snow around the house, reading old issues of Le monde diplomatique, or walking to the nearest town in search of fresh produce to photograph. We are witnesses to his grief and to his awkward attempts at being in the world. The “savoir vivre” of the title refers, in this context, to the art of etiquette and fine dining, but also to the basic skills required to tend to one’s mental and physical wellbeing.

Lafrance filmed the series in 2018, just after he turned forty. I gathered that this particular milestone had been difficult for him (as it is for many of us) and that he had undergone a process of introspection while staying in the Eastern Townships. As I later learned, he had brought with him all of his video equipment, along with an intention to produce a short film. Lafrance’s working method, for this project and others, is to film alone and to film daily, much like a street photographer who treads the pavement every day in a continual search for images. Self-filming, despite the logistical challenges involved (he is simultaneously actor, cameraman, and sound technician – it’s really quite funny if you imagine what that might actually look like), provides him with the kind of creative freedom he craves. It is also a way of working that allows ideas to develop over time, and in the case of Savoir vivre, it meant that he was able to capture the transition of the seasons from late winter to early spring.

Many of the plot details that make up Savoir vivre are based on Lafrance’s real life, and in fact he wanted the project to act as a kind of tribute to his immediate family (his parents and three brothers are all named in the series, and his brother David is one of the few other characters featured). Lafrance often plays “himself” in his videos, but since the release of this project a number of friends and acquaintances have asked him to reaffirm for them the boundary between reality and fiction. The fact that his very-much-alive father is apparently deceased in the series has been especially concerning to some, even though, as the story’s premise, it is a “lie” that should betray the fictitiousness of the whole enterprise. Lafrance is pretty adamant about the project’s total subjugation to the realm of fiction and he views borrowing elements from his real life as a natural part of writing (in other words, you write what you know). His work in general – including his photographic work – is much more grounded in the art of storytelling than in any particular aesthetic approach. And his impulse to tell stories often goes hand in hand with the conviction that the visual arts community – or, broadly, the figure of the artist – provides excellent material for a good story.

The idea of shaping the footage captured in 2018 into a collection of very short films came later: Lafrance wrote the narration that runs throughout the series – essentially, the story – in 2020. He decided to adopt the series format because he was seeing creative possibilities opening up in the field of television that were not there in the visual arts or in traditional cinema. For him, television and popular culture more generally are areas of expression whose forms can sometimes be surprisingly untethered. The series format allows for a certain type of image or scene to be comfortably repeated, since each episode begins the story practically anew. In Savoir vivre, the repetition of landscape scenes works to place winter and the Eastern Townships at the centre of the narrative. The experiential specificity of the season and the particularity of the place (its geographical identity) are the threads that pull the story forward and determine its shape and ending. For Lafrance, who truly believes that Fitch Bay is the eighth Wonder of the World, the Eastern Townships – and, widening the view, northeastern North America – hold a special visual appeal to which he is continually drawn.

In one of Savoir vivre’s most poignant moments, the narrator (played by actor Richard Thériault as the voice of “Vincent Lafrance” the character) declares, “I adored being an artist.” In addition to dealing with his father’s death, the character is supposed to have recently given up being an artist, which is a kind of death that takes place within. Lafrance wanted to capture the mysterious moment when an individual, after years of struggle or only moderate success in the art world, gathers the courage to admit defeat and quit art. It was part of a line of questioning that he had been pursuing regarding his own career: how long he could continue to identify himself as an artist without making or showing that much art. Of course, the character “Vincent Lafrance” takes refuge in his job as a culinary photographer, though his distinctly artsy style does end up gaining the attention of a Parisian contemporary art gallery. The contradiction is not lost on Lafrance that the method by which he impersonated a man who has quit art is art. In sum, the act of making ultimately negates the truth of the story.

So, he hasn’t quit; yet, I doubt that he will ever stop questioning, or making a heavy dose of critical self-consciousness part of his practice. The line between reality and fiction is indeed blurred in his work, simply because he puts so much of himself into it. Vincent Lafrance is actually one of the most genuine people I know. Excerpts translated by Käthe Roth

Zoë Tousignant is a photography historian and curator based in Montreal. She turned forty in 2018.

Vincent Lafrance, born in 1978, holds a bachelor’s degree in photography from Concordia University. He has exhibited his work in Canada – in Montreal (Galerie Division and Galerie Simon Blais), Quebec City (Centre VU), and Toronto (Contact Festival) – the United Kingdom, France, and Mexico. His works are in the Hydro-Québec and Ville de Laval art collections and in private collections in Canada and the United States. Since 2016, he has taught photography at Champlain College in Lennoxville, Quebec.

www.vincentlafrance.com

[ See the magazine for the complete article and more images : Ciel variable 117 – SHIFTED ]