[Summer 2024]

Visualizing the Past

by Kelly Midori McCormick

[EXCERPT]

The exhibition From Slander’s Brand takes as its starting point the impossibility of representing historical events from a singular, one-to-one relationship with reality. The title, referencing Herodotus, the “father of history” – and, for some, the “father of lies” – asks viewers to question the truth claims of those who write history and what it means to document and represent the past.

In the fifth century BCE, when Herodotus compiled myths, genealogies, descriptions of geography, and ethnographies into what many historians believe to be the first systematic history written in the Western tradition, myths were seen as forms of truth. It was only relatively recently in historical terms (the nineteenth century) that notions of objectivity in relation to historical writing settled around ideas of measurable, unbiased truth. And yet, as each artist in this exhibition demonstrates, myth-like storytelling is still a living and breathing part of the way new histories are written by political factions, and it can be an active tool in critiques pointing out the scale of media cycles. Through exhaustive compendia of news production, painstakingly produced text-paintings, and intermedia relationships built across photographs and collections of books, each artist shows how allegories and fabrications are always visible.

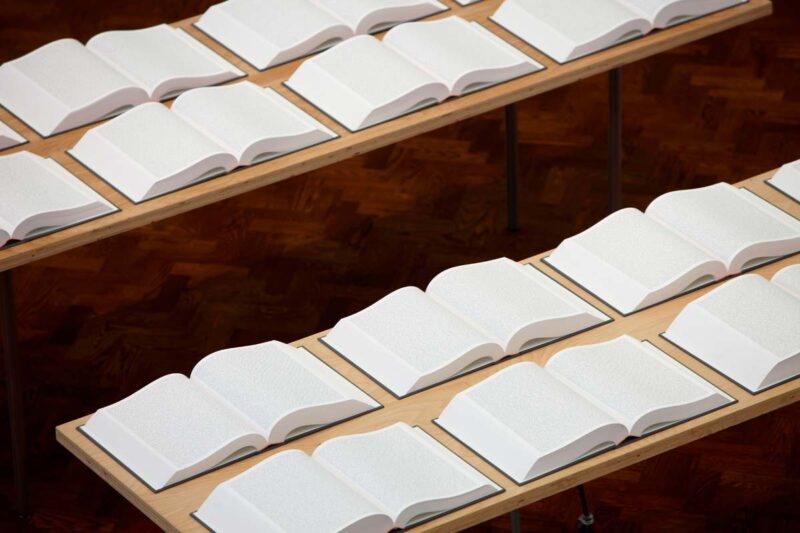

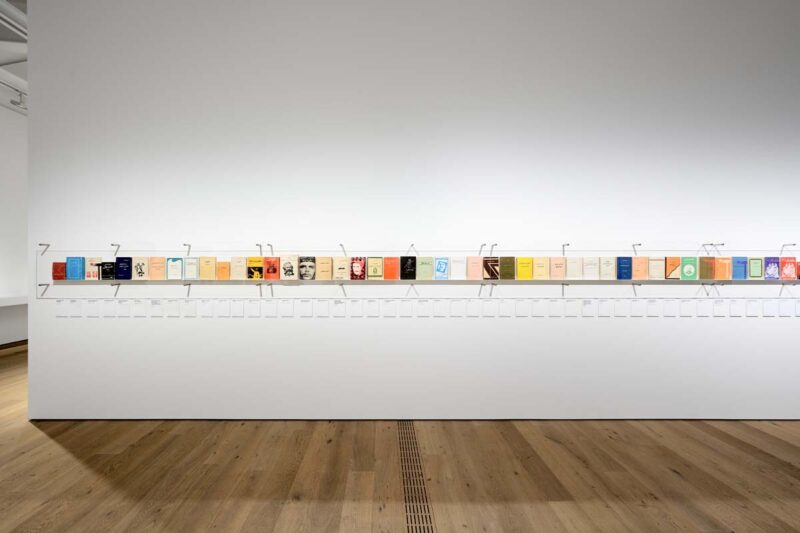

Herodotus introduced his Histories by writing that its “purpose is to prevent the traces of human events from being erased by time”; Rachel Khedoori takes up this ancient goal and applies it to cataloguing every instance of the publication of news articles found online using the search terms “Iraq,” “Iraqi,” and “Baghdad” from the start of the Iraq War, on March, 18, 2003, to 2008. Pulled from news outlets around the world, translated into English, and printed in a continuous flow of text in seventy large hard-bound books, these records of media representations of the war are placed on long tables at the centre of the room; stools invite viewers to spend time with them.

What possibility for finding a “real” past does this work present? In 2023, as viewers sit at the tables and inspect them, the books stand as an overwhelming record against forgetting the Iraq War as the current news cycle incessantly moves us on to the next war, atrocity, and ever-unfolding pandemic. The collective immensity of the textual data in the books engulfs readers, however, making it impossible to grasp the particular as they are swept into an unbroken sea of words. This work is often characterized as making the concrete “indescribable.” I argue, rather, that in its meticulous goal of inclusion it mobilizes description to create a representation of media history that is incomprehensible. Impossible as it would be for anyone to read the thousands of pages of text and make a narrative from them, the story that Khedoori tells is of the unfeasibility of using empirical methods to make meaning and the unattainability of grasping every word of media coverage from within the real space of the gallery.

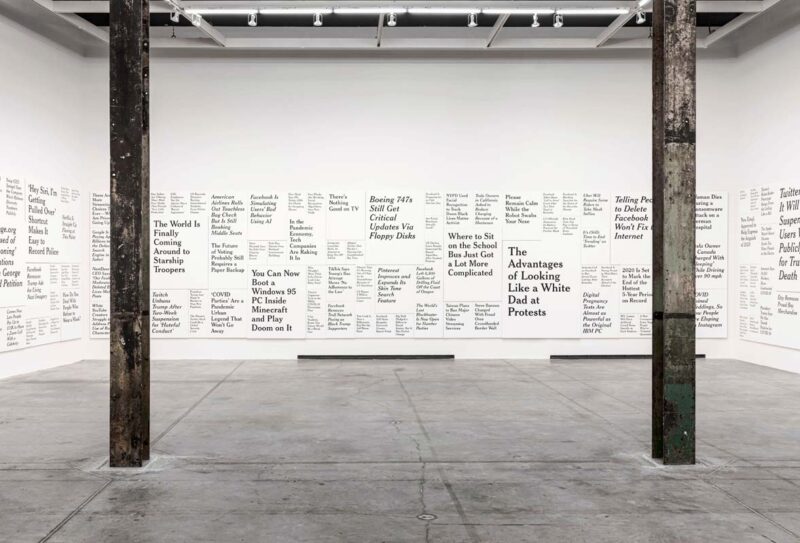

Framing the long tables of Khedoori’s text sculptures, the 325 paintings selected from Ron Terada’s TL;DR series of 473 ten-foot-tall text paintings are hung without gaps and stretch across 205 feet of the gallery’s walls, filling every possible vertical space with news headlines taken from theverge.com. As if in tongue-in-cheek response to Kehdoori’s seventy volumes, TL;DR (internet slang for “too long; didn’t read”) uses very different visual strategies to overwhelm viewers. Terada began TL;DR in 2017, meticulously translating the headlines into paintings in the font used by the New York Times, and increased their size in 2020. The paintings present headlines covering the COVID-19 pandemic, the Black Lives Matter protests, and Trump’s attempt to delegitimize the American elections. Titles such as “Please Remain Calm While the Robot Swabs Your Nose,” though humorous, produce the effect of taking viewers back to the state of fear and the absurdity of those times. Terada has said that “text is the most direct form of communication,” and he uses it to highlight our inability to synthesize meaning when bombarded by such high volume of content. In translating the text of news headlines into what the Polygon Gallery calls “monumental history painting,” Terada seeks to take information usually residing in the detached spaces of augmented reality and present it in a material form that connects it with viewers. The works describe events that took place only three years prior, so as readers walk and read they are jolted back to vivid moments in recent history; the headlines serve as the titles in a vast library of references to the collective trauma of those times.

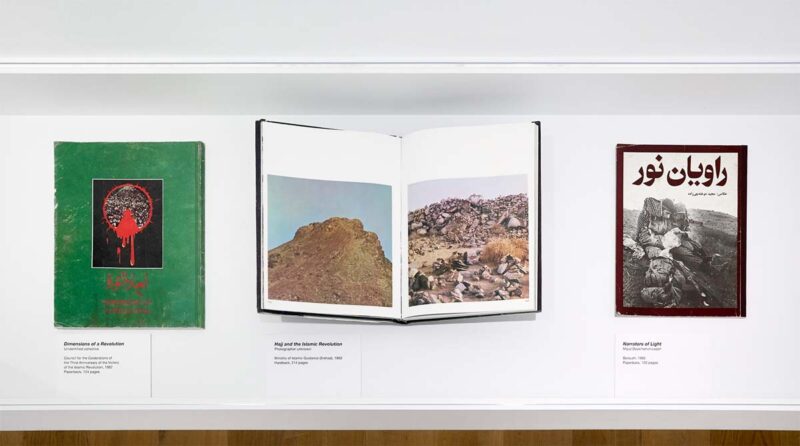

As historians studying the writing of history from ancient to modern times have pointed out, the past is “always a subject to be constructed” and each generation “resurrects its own past” (Moses Finley). This is a lesson drawn out in a third strategy of history making in the show, the books-as-painting installations of R.H. Quaytman. For Quaytman, it is not the task of the historian to find an objective past but rather to draw attention to the construction of historical narratives. She has said, “History isn’t a thing that just exists, it’s something that is continually reinterpreted by different historians, different epochs, different cultures, different genders, different races.”

The display of books that Terada’s and Khedoori’s works invoke inspired Quaytman to extend her investigation into the history of painting-as-books, specifically the question of how books are objects in the world that belong to different epochs and that perform different functions over time. The set of paintings shown in From Slander’s Brand is part of her ongoing series 5 Deaths, which is organized around the themes of mourning and absence and the function of painting in relation to memory and the traces of lived experience. The installation comprises five paintings, each of which was made in response to the death of a close friend or family member, and each of which bears the subtitle of one of the five books in 5 Deaths. With these works, Quaytman also returns to an investigation into the construction of painting in relation to the space of the gallery and the context of display. The paintings in 5 Deaths take up the format of books to draw attention to the materiality of painting in relation to the materiality of the book. Like Terada’s TL;DR, they make visible the process of translation from digital to material form. But where Terada reproduces headlines in text form, Quaytman examines the interplay between painting and text as forms of representation and memory. For her, the function of the book is to contain within it “a trace of a life lived, lost, and mourned.” In the way that a book is something that can be opened and closed, it is a symbol for memory, and in its material form it is a record of time.

Quaytman’s installation, like Khedoori’s and Terada’s, invites viewers to consider the politics of the archive and of memory. While Khedoori’s massive archive challenges viewers to make sense of the past by making the concrete indescribable, and Terada’s monumental history paintings overwhelm the senses, Quaytman’s paintings-as-books ask us to consider how the book as a form – in its capacity to contain memory – mediates between the realms of the visible and the invisible, the present and the absent. Where Khedoori’s and Terada’s works raise questions about the nature of historical evidence and representation, Quaytman’s works offer a meditation on the role of painting in relation to memory and loss.

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 126 – TRAJECTORIES ]

[ Complete article, in digital version, available here: From Slander’s Brand, Visualizing the Past – Kelly Midori McCormick

]