[Summer 2024]

by Sophie Guignard

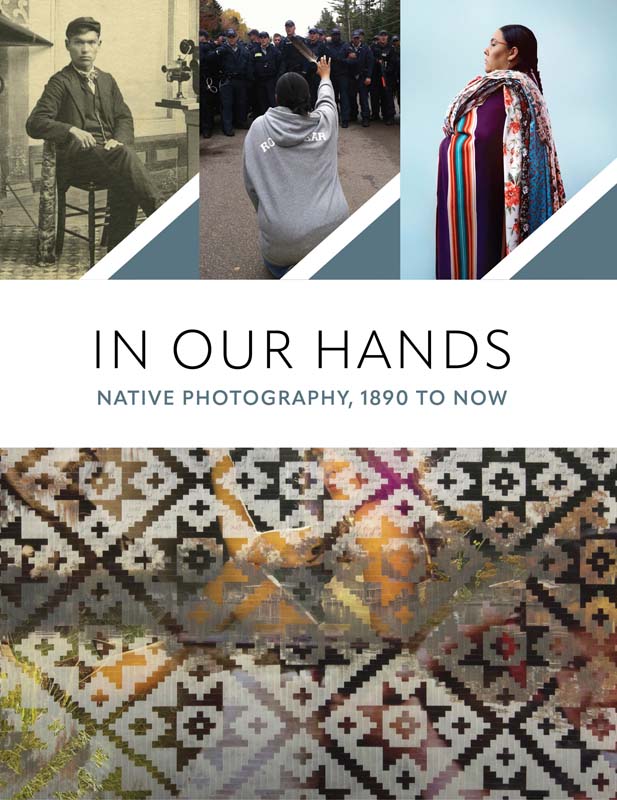

In Our Hands: Native Photography, 1890 to Now is the catalogue for a major exhibition at the Minneapolis Institute of Art that featured Indigenous photographers who worked between the late nineteenth and twenty-first centuries. The co-curators guest curator, photojournalist Jaida Grey Eagle (Oglala Lakota); the museum’s associate curator of Indigenous art, Jill Ahlberg Yohe; and the holder of the museum’s Chair for International Contemporary Art, Casey Riley – worked alongside a curatorial council of fourteen people – artists, researchers, and curators, most of them Indigenous – to mount this historical panorama of photographic practices among First Peoples from the Rio Grande to the Arctic Circle.

Although the project stands out for its scope, the initiative is not the first of its type; group exhibitions presenting First Peoples photographers go back to the early 1980s. However, the catalogue published for In Our Hands makes an important contribution. Thanks to its size, its historical breadth, and the quality of the images reproduced, the book is one of the most consequential and comprehensive published to date on the subject.

The ambitiousness of the project is affirmed in the introduction, written by the co-curators: it is intended to provide a significant addition to research on the history of North American Indigenous photography and bring to light, in an art museum, the work of First Peoples photographers – a heritage that similar institutions are only beginning to recognize, even though photography has been practised in Native communities for many decades. In the 1980s, the history of photography by Indigenous people was developed, in large part, outside the dominant art circuits and was written mainly by its principal voices: First Peoples photographers, artists, curators, and authors. Notably, all fourteen members of the curatorial council, introduced at the beginning of the book, stand out for their long-term commitment to the advancement and promotion of Indigenous photography through their practice or writings.

The formation of such a council reflects the increasingly widespread propensity of art institutions not only to engage in collaborative approaches but also to base such projects in methodologies respectful of Indigenous modes of knowledge. In their introduction, the co-curators also point out the importance of including in the discussion the actors in this history, which constitutes “a parallel ecosystem of photographic knowledge, mutual assistance, collaboration and training, and historical record-keeping that our own training had largely overlooked.”

Beyond the involvement of the curatorial council in the choice of images and photographs presented, the thirteen essays in the catalogue reflect this collaboration: eleven are written by council members and the other two by the curators. The expertise of renowned specialists in Indigenous photography, such as Veronica Passalacqua, director of the C.N. Gorman Museum, and researchers and historians such as Emily Voelker, Laura Wexler, and Amy Lonetree, sits alongside personal reflections by Cara Romero (Chemehuevi), Shelley Niro (Mohawk from the Bay of Quinte), Rosalie Favell (Métis), and Will Wilson (Diné), who are among the best-known Indigenous artist-photographers of their generation. Two texts on the legacy of historical photographers Benjamin Haldane (Tsimshian) and Horace Poolaw (Kiowa) – written, respectively, by Mique’l Icesis Dangeli and Tom Jones – and an interview with the curator Rhéanne Chartrand on the history of the Native Indian/Inuit Photographers Association complete the overview and add depth. As a whole, the book offers a survey of the significance of photography in Indigenous art and cultures since the nineteenth century, while bringing out the different ways the medium has been used, both historically and in contemporary times. What is missing, however, is an overarching essay that would weave a unifying narrative for this panorama, discuss the extent of its ramifications, and describe its diversity.

The strongest feature of the catalogue, no doubt, is the quality of the reproductions and the prominence they are given. Sixty-three Indigenous photographers and artists are represented in more than a hundred and thirty works, making the book the most exhaustive to date on the photographic practices of North American Native people. In its pages, we discover the extent of their production: from the classic studio portraits made by Benjamin Haldane in the early twentieth century to Will Wilson’s Indigenous Photographic Exchange Project in which he revisits the ferrotype technique, as well as documentary images by James Brady (Métis), Peter Pitseolak (Inuk), and Lee Marmon (Laguna Pueblo) and the elaborately staged photographs of Dana Claxton (Húŋkpaphˇa Lakota) and Meryl McMaster (Nêhiyaw). This is not to mention the “photographic weavings” of Sarah Sense (Chitimacha/Choctaw) and the baskets of Shan Goshorn (Cherokee) woven from photographs. The importance of the medium as material and discourse is also conveyed through the presence of emblematic works by contemporary artists such as James Luna (Puyukitchum/Ipai/Mexican American), including images from his celebrated performance Take a Picture With a Real Indian (1991). This wide range of methods and practices reflects the richness of the medium in terms of both information and creation.

One may wonder, however, what motivated the division of photographs into the three parts that structure the catalogue, which reprise the exhibition’s three themes: “Always Present,” “Always Leaders,” and “A World of Relations.” No explanation is given about the choice of these themes to encompass the diversity of photographic perspectives; despite the eloquence of the titles, I would have liked to understand why the images were found in one category rather than another.

Nevertheless, In Our Hands is an important and long-awaited book. It fills a gap in the literature on the history of Indigenous photography by Indigenous people and has all the qualities to become a reference on the subject.

Translated by Käthe Roth

—

Sophie Guignard is a doctoral student in

art history at the Université du Québec à Montréal, with a speciality in photography studies. Her research focuses on Indigenous self-representation through photography

in catalogues for group exhibitions by Indigenous photographers in North America (1980–2010). She holds master’s degrees in cultural policies and in political science from Université Paris Cité.

—

[ Complete issue, in print and digital version, available here: Ciel variable 126 – TRAJECTORIES ]

[ Complete article, in digital version, available here: Jill Ahlberg Yohe, Jaida Grey Eagle et Casey Riley, In Our Hands – Native Photography, 1890 to Now — Sophie Guignard ]