[Summer 1994]

by Peter Duthie

In Western Canada, more specifically Alberta, many photographers give the prairies a passing glance before losing themselves in the breath-taking pictorial beauty of the Canadian Rockies.

For them the prairies offer nothing to capture on a sheet of film: no grandeur, no drama, no “eloquent” light that Ansel Adams made universally sought-after. The Canadian West though, is no stranger to a certain breed of photographer working in the style of the New Topographies. Attempting styles of, for instance, Lee Friedlander, Lewis Baltz or Robert Adams these photographers render the land as ecologically threatened by encroaching development or represent it much the way geological-survey photographers may have a century ago. Some are successful, but many produce photographic prints that become confused political-aesthetic statements. Their prints are exquisitely printed, but they speak of highlights and shadows more than urban development and of delicate nuances of tonality more than social turmoil. They become emotionless non-statement devoid of a fresh, personal vision.

“Desolate? Forbidding? There was never a country that in its good moment was more beautiful. Even in drought or dust storm or blizzard it is the reverse of monotonous, once you have submitted to it with all the senses. You don’t get out of the wind, but learn to lean and squint against it. You don’t escape sky and sun, but wear them in your eyeballs and on your back. You become acutely aware of yourself. The word is very large, the sky even larger, and you are very small. But also the world is flat, empty, nearly abstract, and in its flatness you are a challenging upright thing, as sudden as an exclamation mark, as enigmatic as a question mark.”

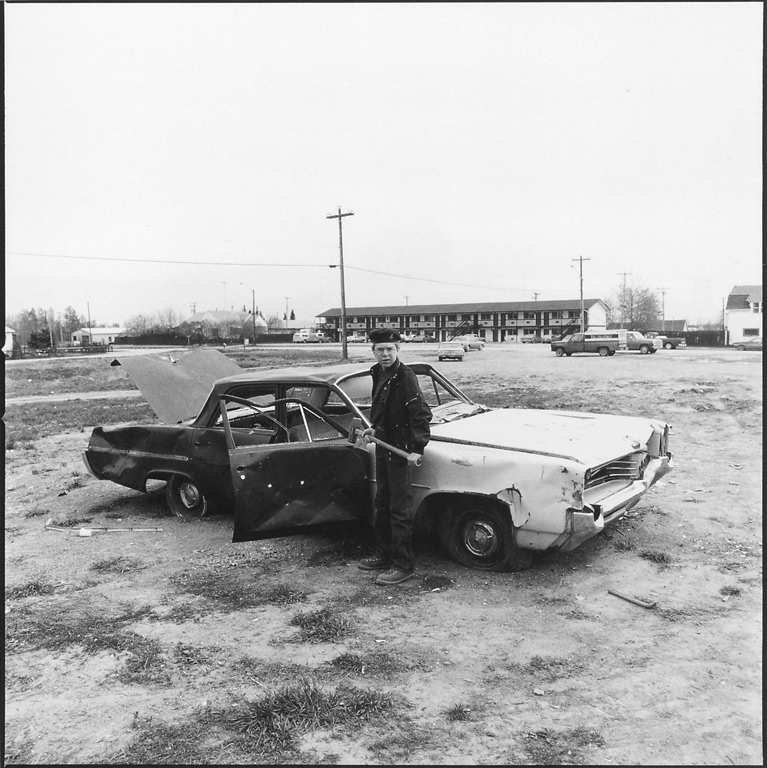

As for Stegner, there is for Webber a strong emotional connection to the prairie landscape, to the enigmatic beauty of the “flatlands” of this country and to the people who populate it. Rather than subordinate this emotional connection to a higher aesthetic order, Webber makes it one of the pillars supporting his work. Webber labels photographs without a sense of emotive power as “puritanical”. He sees photographers who produce this kind of work as “stepping back from emotion,” as producing “emotional bleakness,” as being engaged in a “kind of protestant work ethic.” Webber, a devout man himself, considers himself more “catholic” in his approach to photographing the prairies. He brings to his work a sense of ritual, mystery and celebration. In this Catholic framework, the landscape becomes a symbolic backdrop of sky and land, an abstraction of God in front of which is played the drama of human existence.

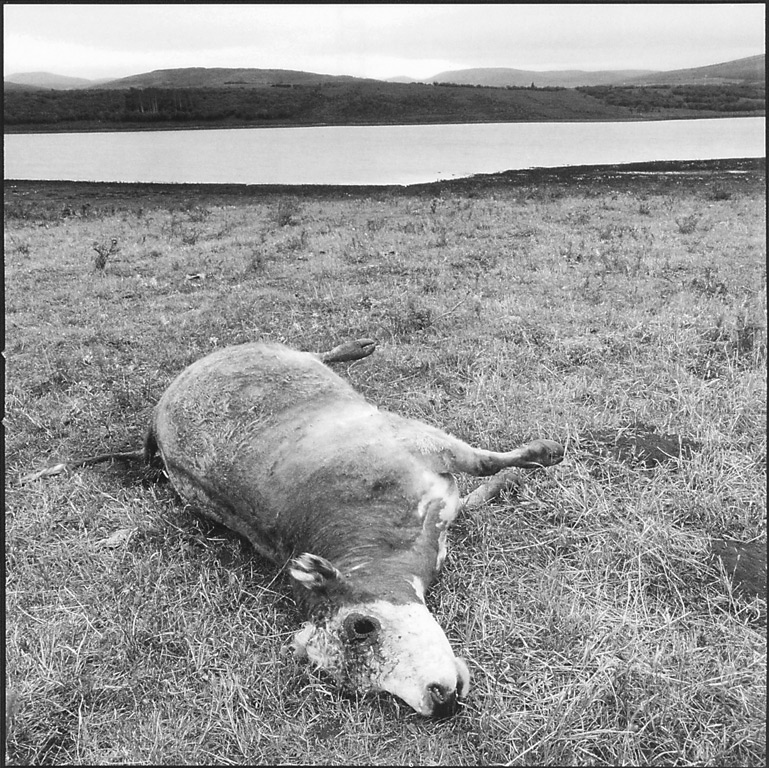

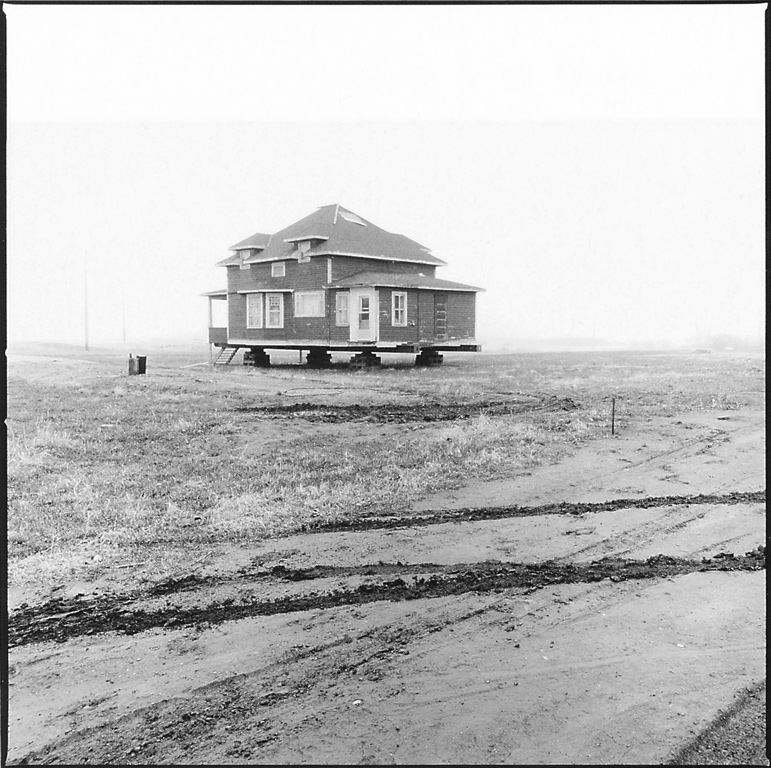

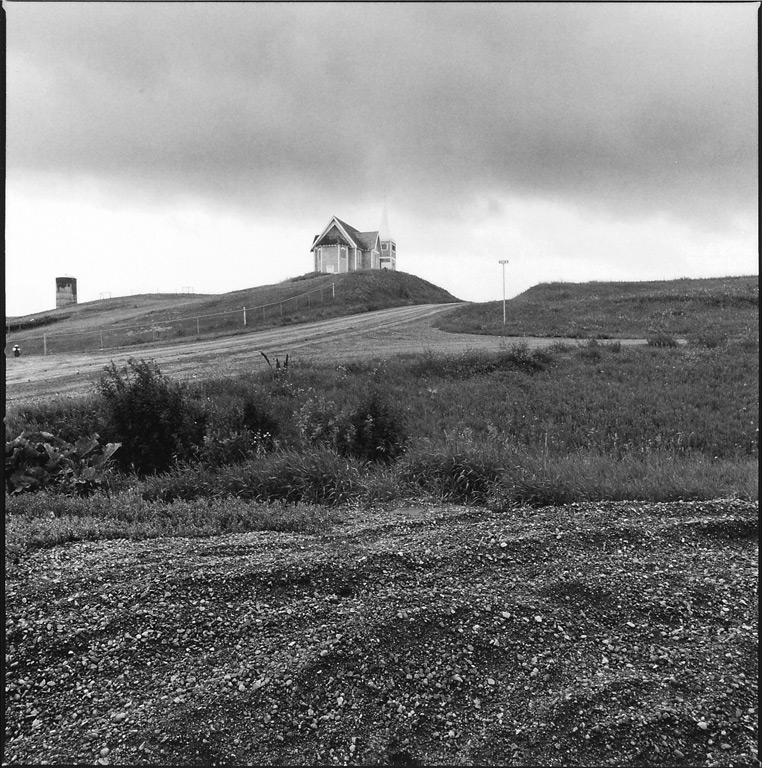

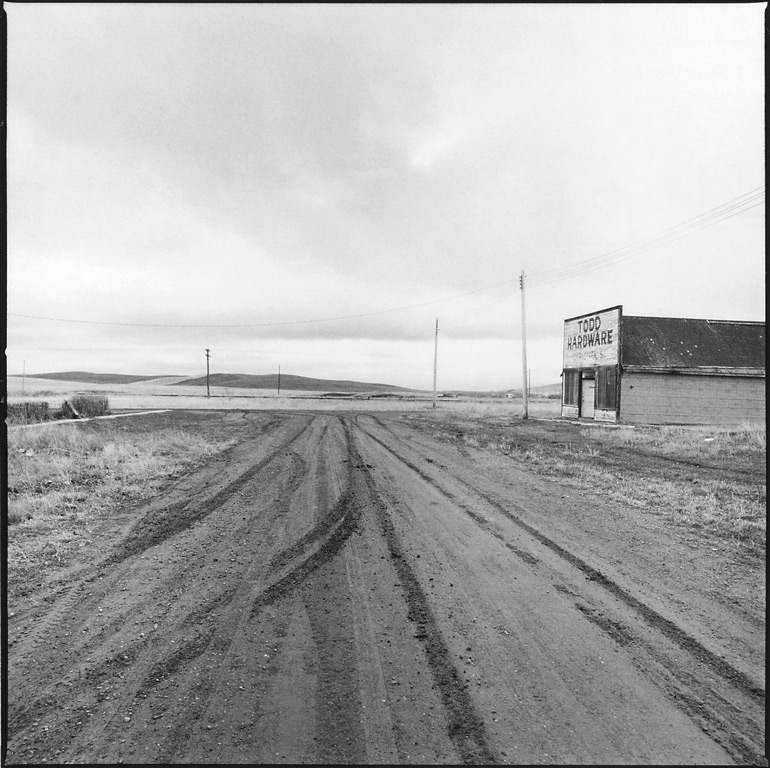

He tears down the cliché we have all helped to create of the prairies. To many of the prairies are the forgettable flatness that lies vacant between two highly populated coastal populations. It is the fertile heartland, the breadbasket of Canada, the great expanse of checkerboard wheat field that photograph so well from the air for glossy coffee table books. But Webber pulls our attention to a different Canadian prairies. Like other photographers before him, Robert Frank, Henri Cartier-Bresson and Josef Koudelka to name only a few, he is drawn to the “vanishing” things in our experience. Cartier-Bresson once wrote in his Decisive Moment, “Photographers deal in things which are continually vanishing, and when they have vanished, there is no contrivance on earth which can make them come back again.” The only signs of prosperity in Webber’s photographs are in signs themselves, in one photograph two beautiful children groomed and dressed to high urban standards, glow from a highway billboard. Above them stretches a vacant sky; below, in equal proportion, an expanse of wet asphalt. Everywhere else we see conditions of decline. An Alberta Wheat Pool elevator lies levelled in a heap in fields empty of wheat. A boarded-up hardware store sits vacant where there is no obvious need for hardware. Homes that once sheltered growing families sit vacant and are either obscured by trees, as if they were being consumed or strangled by the vegetation, or depicted sitting on blocks like a spacecraft waiting to be jettisoned into space. Only one half of a train station sits along a train line where trains no longer run. All these structures, evidence of human habitation and struggle on the prairies, sit in a dynamic tension between earth and sky. There is compositionally, in Webber’s photographs, a constant movement back and forth between earth and sky. Invariably the horizon cuts Webber’s frame in half: a blank grey sky meets a cold, black earth. Human structures do not stand proud against the sky; if there is that possibility, mist obscures them. For the most part these structures are being eroded and pressed into wet, dark, brutal earth. It is no coincidence that the only structure that stands on the only raised horizon, clearly depicted against the sky, is a church.

Through Webber’s photographs the prairie becomes a passionate metaphor. It is a passion play of man’s stoic struggle in life. His images celebrate a photographic mass. His portraits show quiet resolve and acceptance of struggle: those that reveal any defiance or pride are either obscured or encroached upon by shadow. He points to that “question mark” of our existence. In the Swalwell photograph a farm sign depicting a prosperous farm in the process of being cultivated by farm machines is centered in the frame. The sign’s horizon meets the prairie horizon an ironic reminder of the crushing vastness of the prairie. First, we are fooled by our urge to see deeper. We stare at the sign and are ultimately forced to commit the sin of pride; to revel in the works of man. Yet one glance to either side, top or bottom of the sign, and we are confronted by the blankness of the sky, the abstraction of the horizon, the roughness of the earth. We feel the full impact of a world that will level us all and a sky that will offer us no answers. Unlike the photographs of the new topographical movement that were published in a book entitled New Topographies: Photographs of a man-altered landscape, George Webber’s photographs speak more about a land-altered humanity and the spiritual dilemma that this alteration poses.

Bachelor of Arts, University of Alberta and Bachelor of Journalism, Carleton University, George Webber supervises the Art and Photography Unit at the Southern Alberta Institute of Technology. Webber also teaches photography. His work has been seen in numerous exhibitions since 1977 and can be found in several public and private collections in and outside of Canada.

Peter Duthie is the owner of Folio Gallery located in Calgary. Folio, the only commercial photography gallery in western Canada has been showing the work of international and Canadian photographers for over a decade. Mr. Duthie also teaches at Calgary’s Mount Royal College.

![[gallery ids="96787,96789,96791,96793,96795,96797,96799,96801,96803,96805"]](https://cielvariable.ca/wp-content/uploads/1994/06/27_36_Webber.jpg)