[Fall 1994]

by Lisanne Nadeau

L’anonymat de l’âme1

Through a gaze both anxious and passionate, Richard Baillargeon seeks temporary shelter. He explores territories of the individual, which he describes as “the universe of what is near.”

To better understand the path the artist has chosen, let us look back to when the idea of travel was central to the thematic content of his oeuvre. Amongst other works reflecting the theme of travel are Transit Commedia (1985), produced in Great Britain, and D’Orient (1988-89), produced in Egypt. Appropriately, the panoramic format of these pieces afforded a considerable view of the landscapes. Soon, however, the voyage was to become synonymous with a more intimate course, with an interior search: a quest. Shortly after finishing D’Orient, Baillargeon created Comme des îles (1987-89), a series of travel photographs devoid of all vanishing points. They resembled a succession of metaphors of urgent movements of the soul: cages in menageries, fragments of vegetation enclosed in glass, cropped photographs taken from press clippings. Neither D’Orient‘s exoticism nor the artist’s previous vast horizons, enticing our eyes to scan and travel across the surfaces, are apparent in this series. Views are blocked and foregrounds are immersed in a persistent mist, in a heavy black texture that makes one hold one’s breath. The images appear to be spread out in fits and starts as a stirring soul, or in the way a labyrinth leads one to indefinitely return to self, to one’s initial doubt. Baillargeon’s quest was unmistakably troubled. And this feeling of uneasiness persists throughout his work until today.

In 1989, with a piece entitled Les cartes égarées, part of the collective production Dérives: objets, suites et traces2, his work undergoes considerable change.

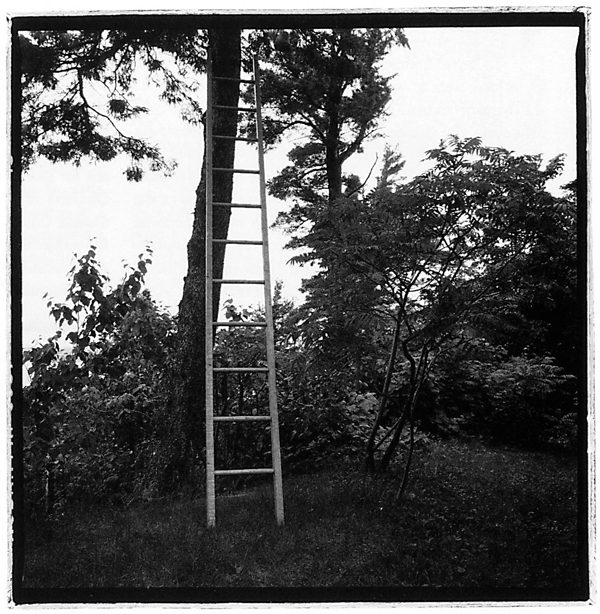

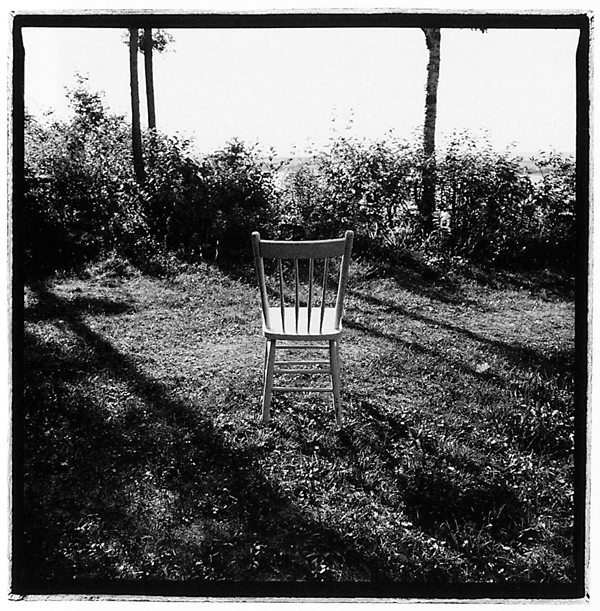

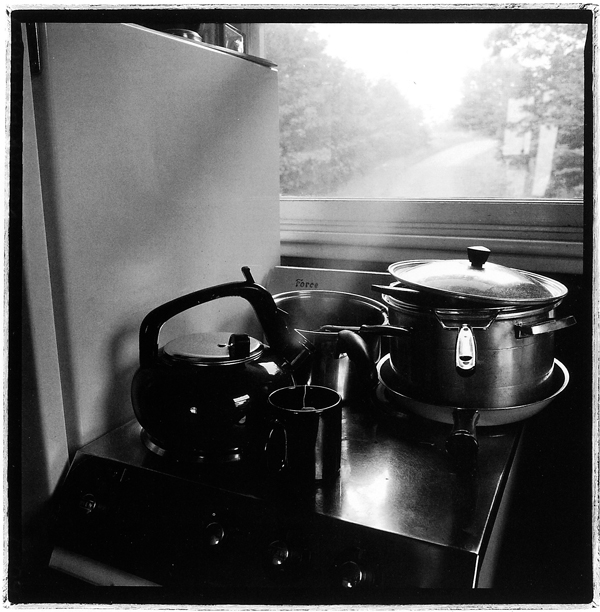

In this production, Richard Baillargeon seeks to create dense, intense, profound and enigmatic images with a paradoxical economy of means: a few objects, parcels of nearby nature, and a striking square format. His work is no longer about the itinerary of the eye swiftly scanning the horizon. It is instead an endless search, affording not only the exploration of territories of the individual, but also of our private and daily spheres. He longs for intensity in starkness, for a place where uneasiness is expressed and questioned from within the very universe of what is near. The importance he bestows upon the object arises from a selective and monumentalizing regard. Although Baillargeon’s representation of daily life may be somewhat surprising, it is neither entirely strange nor estranged. In fact, daily life with this artist is a portrayal of the livable, and more so, of residency. Equally charged with metaphors of human – yet nameless -presence, his work reveals a subject matter shadowed by anonymity, by anonymous objects. However, these objects seem to have become identifiable with the subject, the artist.

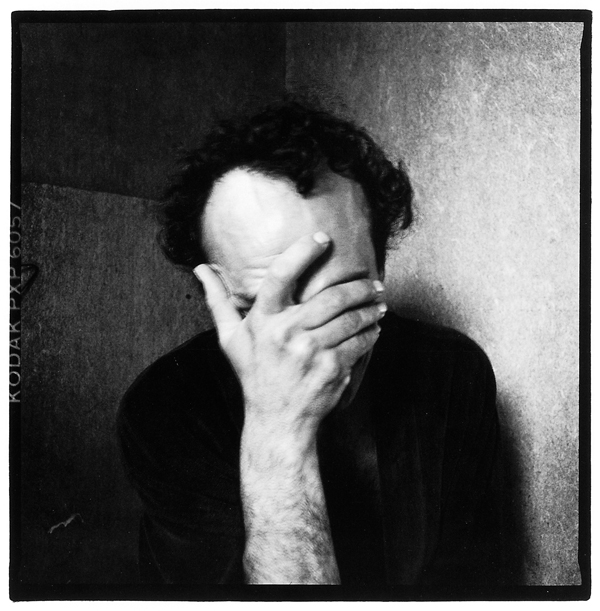

Previously, Richard Baillargeon’s style has been considered autobiographical. A similar association would be unlikely today. His use of anonymity enables a discourse that speaks much more of individuality than of self. In one of the portraits of Champs/la mer, the subject hides behind his hand. He is hiding out of humanity rather than modesty: what is important here is the image’s human attribute, not the face that signs it. Similarly, the act of showing oneself while simultaneously hiding is not an indication of hesitation as much as a will to signify the subject’s presence, along with the unimportance of his specific identity. The photographer conveys a world of solitude beyond the constructed identity of restrained singularities.

In Champs/la mer, closeness, or what is near, is fundamental to the articulation of the series’ very meaning. Images such as landscapes are nevertheless integrated into this series, suggesting a revival of what had previously animated the artist’s production. But these landscapes3 greet us differently. We must encounter them through our regard. They are no longer planes, as in Transit Commedia, in which the photographer is nestled, or is circulating. Instead, the body is immobile, nearby, and it is the regard which discloses the appearance of things. Once again, prohibiting all lateral motion, the format controls the movement of our regard, directing our focus both on the object and the parcels of landscape, generally investing them with a heraldic value.

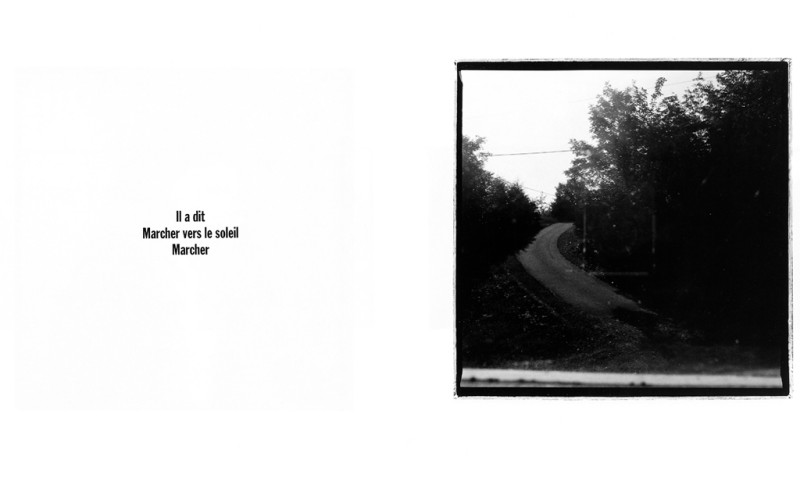

In the window, a path leading beyond. The rest may be imagined, all the more intensely due to the absence and imaginary that fulfil the glass opening. I recall Caspar David Friedrich, perhaps the first to have painted the outside as seen from the recess of a window. A simple feat. And yet, could it not be a true metaphor of human solitude, of a subject reflecting upon the reality of the world through this very forlorn state? In a similar manner, Baillargeon explores the limits of what is near and what is exterior. He explores the realms of where we simultaneously converge and diverge.

There is also melancholy. We are able to sense it without quite knowing why. The atmospheric density, the light of a day’s end, and the banality of a few objects imprint our gestures and what we are. Then, the sky. Clouds embraced by the viewfinder’s frame, an infinite obscurity incised by a flash of lightning, and again the sky, spreading beyond the pier. Thus, an inevitable calling, a tension, with the near and the infinite in constant dialogue. The reference to the German Romantic becomes clear. With Baillargeon, just as with Friedrich, the subject remains inscribed in its overly human dimension, affording the recognition of the acute gap between the dichotomic wills – near and far – to transcend.

Here, portions of domestic space, objects and furniture reminiscent of human gesture cohabit with views of a house, a sky, and a storm. Our gaze is summoned back and forth, from one photograph to the next, and at times, from within a same frame.

In the window, a path. The camera’s reflection indirectly – in a metonymical way – redirects us toward the subject. Moreover, from our concrete reading of the space, which constantly redirects our attention to the foreground, to the plane of the photographic shot, we are again oriented toward the subject. Even the shots of sky are not entirely distinct from either their framing or the eye that delimited them. Elsewhere, photographs of smaller format invest closed spaces. An isolated chair suggests the presence of a regard piercing an indefinite horizon, at once discernible and absent. Such an image inevitably brings one back to self, to an individual and solitary territory. Enthralling meanders through a field of reeds in a ground shot recall some of the closed spaces in the series Comme des îles. Somewhat like a quest in an inextricable space.

“Images and words are fragile and fleeting things that usually slip and steal away when confronted with a will to reduce their scope and meaning.”4 They are elusive. Arising from intimate experience, they search further, beyond. They strive to articulate a fundamental questioning of human existence. Words quickly surpass the personal sphere to take on certain romantic characteristics. “He” and “you” suddenly become generic. The fictitious landscape admits projections of the subject. The objects, the table, the broken glass – all near -, convey a saddened violence echoing above and beyond one of life’s isolated moments.

Perhaps this work portrays fiction as a shelter for personal territory. Or instead, fiction may be a springboard, a means for the universe of what is near to forsake the biographical. And in this context, why then would the landscape not metamorphosis itself to augment the voices of the soul, to give greater expressive range to varying states of mind?

Translated by Jennifer Couëlle

1 This essay is an adaptation of the catalogue text for the group exhibition Quatre histoires ou L’éthique du doute, curated by the author. Presented from December 1, 1993 to February 27, 1994 at the Musée régional de Rimouski, the exhibition comprised works by Richard Baillargeon, Michèle Lorrain, Guy Pellerin and Sylvie Readman.

2 Presented in 1989, at Quebec City’s LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE, this collective production comprised the works of Richard Baillargeon, Jean-Pierre Bourgault, Jacques Coulombe, Hélène Godbout, Lisanne Nadeau and François Robidoux.

3 The Russian philosopher Mikhail Bachtine perceived the emergence of the landscape in ancient literature as a sign of a new and “private” consciousness: “Then came the birth of the ‘landscape’, of nature as both the horizon (object and vision) and the environment (background, décor) of the private, solitary and passive man.”, “Formes du temps et chronotope”, Esthétique et théorie du roman, p. 290.

4 From Dérives : objets, suites et traces, notes by the artist on Champs/la mer, winter 1993.

Born in Québec City, Richard Baillargeon studied anthropology at l’Université Laval. He is a founding member of VU, a Québec City artist centre for the promotion of photography, and since 1989, has been director of the photography programme of the Banff Centre for the Arts, in Alberta. He was the first photographer laureate for the Prize of the Duke and Duchess of York, awarded by the Canada Council. Richard Baillargeon has exhibited his work in solo and group exhibitions, both nationally and internationally.

Indépendant curator and art critic, Lisanne Nadeau fives and works in Québec City. Active in the collective organization LA CHAMBRE BLANCHE (Québec City art gallery), she regularly collaborates on a variety of projects and publications produced by the gallery. She coordinated the event Mirabile Visu, in 1989, and co-directed the magazine Noir d’Encre from 1990 to 1993. In 1992, in collaboration with Sylvie Fortin, she curated and coordinated Projet 3 – Déplacements for the summer studios of the Centre de sculpture de Saint-Jean-Port-Joli. She recently contributed to an artist book project produced by the artist Paul Lacroix and the binder Jacques Fournier.