[Spring 1997]

by Annie Molin Vasseur

In a text titled Touching the Self, she remarks that her research “consists of exploring personal and universal questions concerning sexuality . . . drawing upon both feminist and psychoanalytical theories . . . as the interior self is built.”

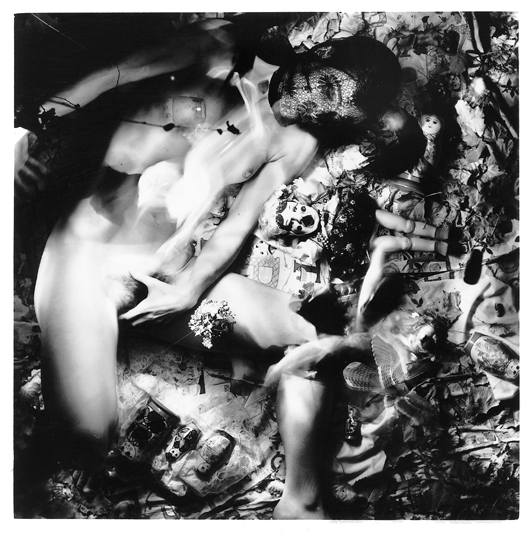

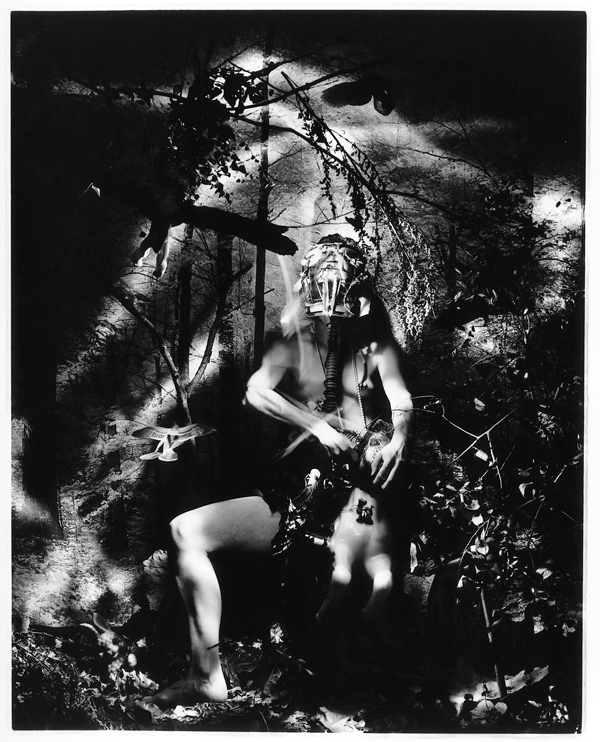

Since 1989, Thorneycroft has been exploring the “self” – to use psychoanalytic terminology – in the form of a body, her own, partly lit in the darkness. A fictional scenario unfurls before the camera’s eye, in which the self is thrust into an imaginary setting. The artist photographs herself surrounded by, among other things, plants and toys – figurations, one might say, of natural and social conditioning. The dim lighting of the scene reveals only an indistinct view, suggesting a partial revelation, an emergence of the unconscious.

In this baroque-style work by Thorneycroft, we glimpse (rather than see) an infinity of details suggesting the complexity and breadth of our mnemonic heritage. We plunge into the collective unconscious via the individual unconscious, in a psychic revelation whose parallel with the photographs is very obvious. Two elements are at work to reveal these impressions: light, which generally symbolizes the awakening of consciousness, and water, which often represents the unconscious. The lighting accentuates the signs that belong to the environment in which the individual is evolving – in this case, the patriarchy.

For Thorneycroft, an encounter with the self, the true being, with all it implies in terms of accepted identity, entails the refusal – even the destruction – of a fabricated self. Two of Thorneycroft’s 1992 photographs, Untitled (Centaur in the Garden) and Untitled (Mabrushka Doll), comprise a theatre of deconstruction of imposed reality, a passage to darkness: a sort of crossing of “the shadow”1in which veiled, masked characters representing family roles display their adherence to the world of archetypes.

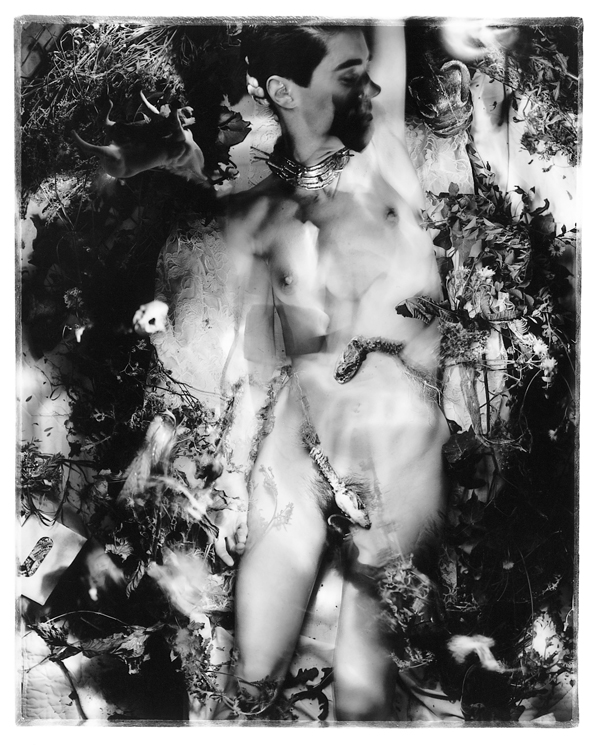

A 1993 diptych, Untitled (Twin), deals with the duality of the self. In a staged setting, masculine and feminine attributes are intermingled, throwing into question the very fundaments of the body – if not in terms of sexual differences, then at least in terms of their interpretations and the roles that have been attributed to them in, and since, the mythic times of lack of sexual differentiation. It is an obvious reminder of the heritage of the psyche’s bisexuality.

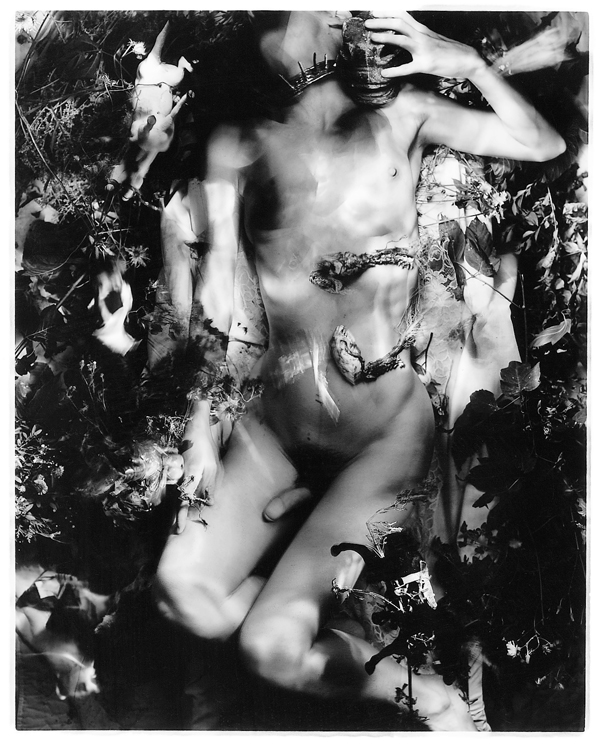

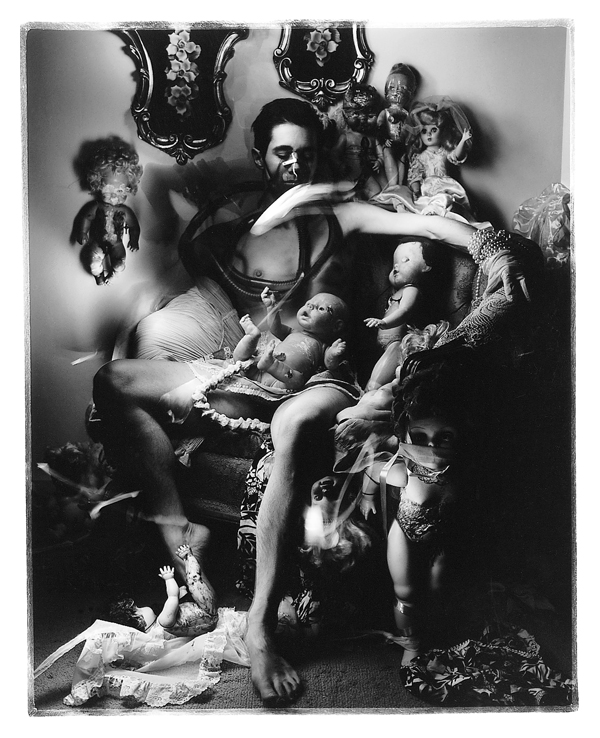

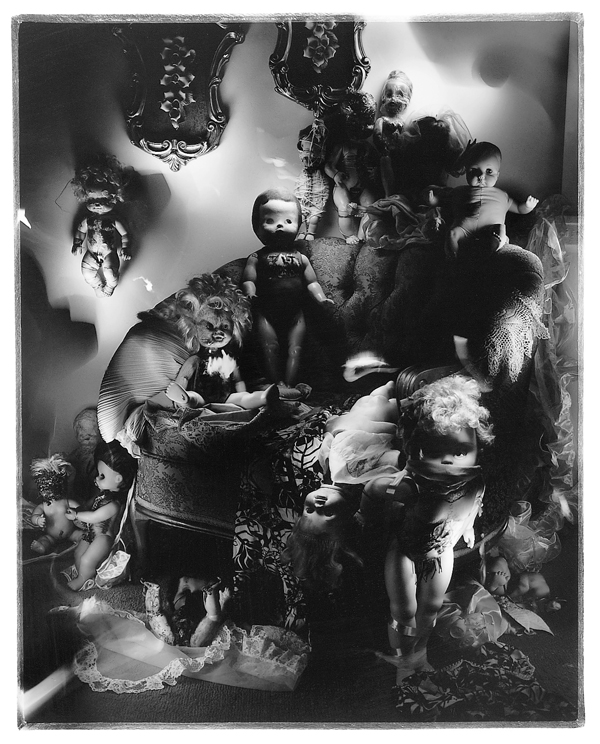

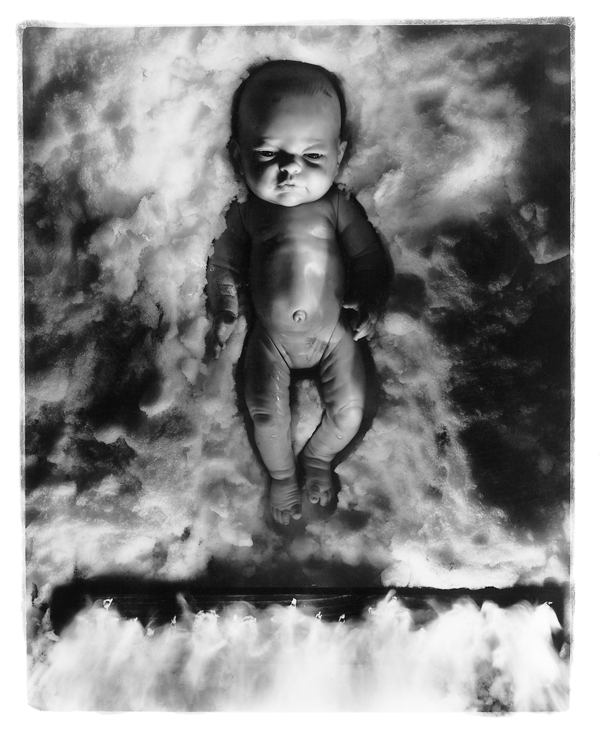

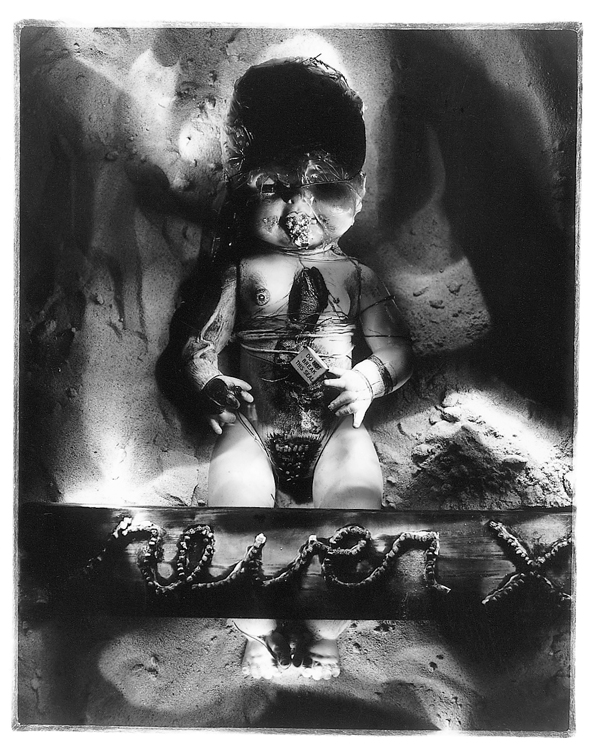

These images seem to lead, in Untitled (Queen Anne Chair) (1994) to a statement of “objective neutrality”: a sort of robotization, in which the baby, the doll, and the little self become a series of photographs, invading the human being’s “royal” space, or simply ejecting the human. Here again, the everpresent shadow conceals the sex of the dolls – toys that are in fact asexual – even though some seem, in the dusk, to have been endowed with sexual attributes. In these photographs, a sort of organized confusion refers back to chaos, to genesis, where everything that denotes consciousness is barely lit.

In other photographs, some dolls are soiled, tied up, or veiled: the artist has marked them with signs of alienation illustrating the small bit of liberty that characterizes these personifications of the self. Seen as “objects,” with the current sexual connotation of this word, have these celluloid or rag-doll babies lost all symbolic attachment to life? In other words, do they lead to a new human memory, in which being born corresponds, above all, to a sense of ideological belonging to which each sex must submit itself?

At a time when science is proving that artificial birth is possible, once fundamental certitudes are now thrown into uncertainty. Many questions surge forth, as if the universal archetypes that nourish the human spirit were undergoing mutations similar to the upheavals that erupt at all levels of what Jung called “synchronicity.” These days, we are witnessing a breakdown in the vertical and hierarchical structures of Western society – notably those in the church, the family, and the corporation, which have been its pillars – and a simultaneous rise in the importance accorded to personal rights, and women’s rights in particular. At the same time, there is a sweeping wave of spirituality that favours the individual over groups – or the reverse, depending on the civilization observed.

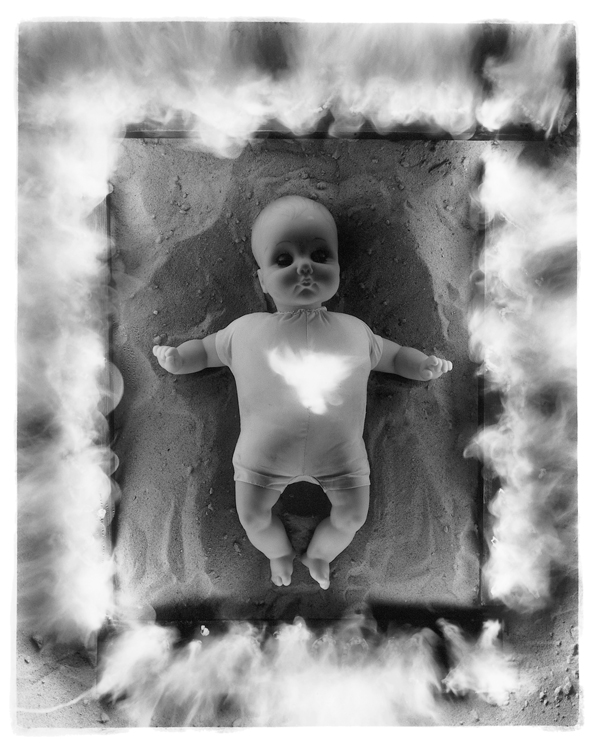

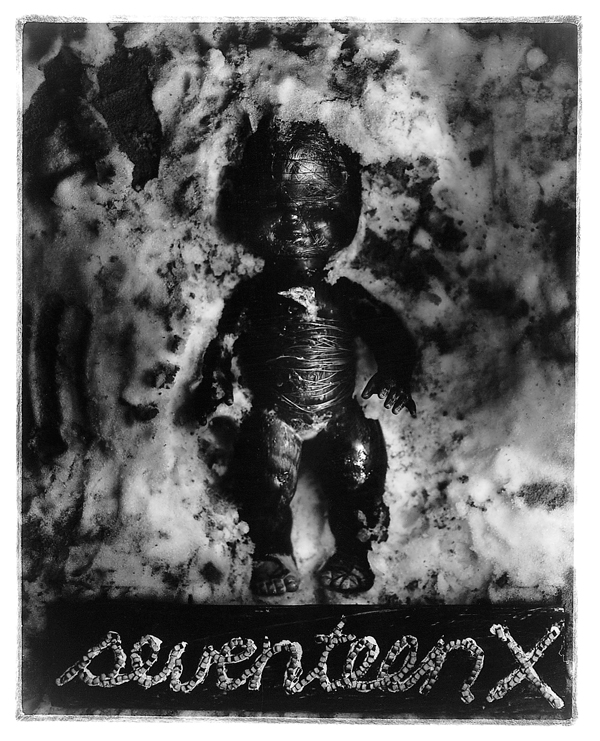

In all this disorder, it seems that for the being to emerge, it must burn away the representations that are now foreign to the self. Thorneycroft indicates the emergence from chaos via a passage by fire: On the Skin of a Doll (Infant Doll on Fire) (1996). And in the same series, we see the spectactular carbonized baby, whose photograph, titled White Bird Doll, bears the inscription “Seventeen X.” The bird, the soul – do they take flight?

One might conclude that collective morality is thrown into question and personal ethics triumph in the photograph in this series subtitled Baby Jesus Doll. However, the enigma remains, because the title refers to a religious assumption. Surrounded with smoke and emerging from darkness, the baby, unencumbered and cleaned of all that soiled it, enters into the white light of what might metaphorically be called the purification of knowledge. Undeniably, given the position of the bather’s limbs, the self is born of a forward impulse that characterizes the union of clarity of thought with action. The doll has an enigmatic, Buddha-like smile, and a large patch of light illuminates its chest. The signs would lead us to read “birth,” an opening to a consciousness of being. But why is it always a doll that is represented? After all, a real baby also appears in this series. Will it be consumed in the test of fire in the destruction of the self, or will it emerge?

Translated by Käthe Roth

Annie Molin Vasseur was co-founder of the magazine Etc Montréal and of the Association des galeries d’art contemporain de Montréal, and she directed Galerie Aube 3995. She has just published a collection of poetry, L’été, parfois (Éditions Bonfort) and her first novel, Zéro un (Éditions de l’Hexagone).

Thorneycroft lives in Winnipeg, Manitoba, where she teaches at the University of Manitoba’s Art School. Her firstsolo exhibition, Touching the Self, travelled to a number ofgalleries across Canada in 1991. Since then, she has exhibitedregularly in Canada and Europe. She is represented bythe Leo Kamen Gallery in Toronto.