[Summer 1997]

Dazibao, Montreal, January 16–February 23

Maison de la culture Côte-des-Neiges, Montreal,

January 23–February 23

While images, whether photographic or other, necessarily give us something to look at, only some remind us that we are looking. And in the case of photography, with its inherent potential for the voyeuristic “gaze,” the sense of sight pertaining to such expository imagery is paralleled by that of the images’ maker, or taker. In fact, it is the very transparency of the photographer’s regard that allows us – the viewers – to recognize that we are looking. In Dazibao’s twofold exhibition Le Paysage et les choses, Quebec City photographer Richard Baillargeon looks by, among other things, weaving words into skies and introducing twin beds and motel settings into prehistoric fauna.

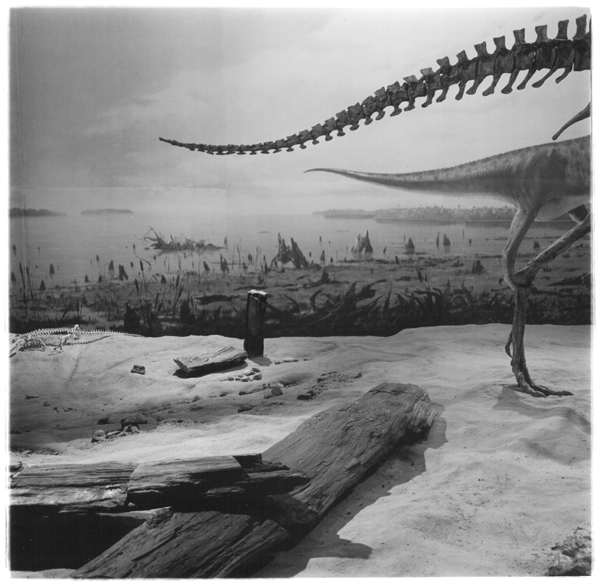

Clouds, places to watch the sun set over water, and dinosaur tails set against the painted backdrops of a palaeontological museum were among the sites strewn in groupings of varying numbers and at various heights along the walls of both Galerie Dazibao and Maison de la culture Côte-des-Neiges. This thoughtfully hung exhibition brought together three, mostly black-and-white, bodies of recent work, all which are characteristic of a strong trend pervading present-day photography: the poetic viewing of the commonplace. And within this broad denomination, Baillargeon – whose purposeful compositions and resolute technique bear witness to his experience – directs our eye through a concentration of tightly cropped images, often juxtaposed with words, framed fragments of thought, which inevitably reflect back upon his own intimacy of vision.

Although these photographs are of uneven visual impact and evocative quality, on the whole, Baillargeon’s work stands strong in its ability to convey the boundlessness and sheer ease of looking, no matter how removed the objects of contemplation. Withstanding, for instance, the somewhat sterile formal analogies between the tall grass and the spindleback chair in a diptych in the Champs/la mer series (1990–94) is the simplicity with which the photographer deconstructs his own regard, leading us to reconstruct and perhaps appropriate its poetry. And as the distance between the images and their subjects remains manifest – as what we sense when viewing them is not so much the affect of, say, a night sky emblazoned with lightning as its uncanny pairing with a stack of pots and pans on a stainless-steel stovetop – what is being stressed here is the poetic freedom of sight. The same is true of the large-scale polyptych in Terres austères (1990–96), in which images of dried, fossilized land, gnarled trees, and flat fields abut museological representations of life past. Here too, the genuine subject appears to be the wandering and mating eye of the photographer, as opposed to the grinning trompe-l’œil age-old shark. To see another look is to look; and to look, this hushed work suggests, is to feel.