[Fall 1999]

by Martha Langford

Last time (the first time), millennial anxiety was deferred by a strategic announcement from the church fathers: the population’s fears of the apocalypse were premature, for the year to worry about was not 1000, but 1033.

Logical enough, and pretty clever, for by then one could expect the people to have forgotten all about it. It would be nice have such a formula now, as we begin the countdown to 2000, walking backwards, as it were, with our eyes fixed on history and memory, especially the “memory” of our personal computers. The path for photographic historians is relatively short, and was nicely beaten down by the 150th anniversary celebrations of 1989. This article throws me back to that time, because my assignment from CVphoto is to consider the artists and issues that marked Quebec photography in the eighties in relation to what signifies now.

Artists have been telling me for decades how much they hate surveys based on (1) thematic criteria; (2) regional criteria; (3) equity; (4) youth; (5) coincidences; (6) evolutionary versions of the culture; (7) any combination of the above, so my acceptance of the assignment seems like a soft form of suicide – possibly my own response to the millennial crisis. Still, there is something interesting about the question – or, rather, interesting about artists at mid-career, the questions that still interest them, and our changing understanding of their work.

What we note, first of all, is a reconsideration of photographic specificity. In the eighties, a steady stream of theoretical studies (philosophical, semiological, poststructural, Marxist, feminist, and/or psychoanalytical) addressed the photographic act, its objects, and its reception. More practically, the distinct nature of photography was argued in the creation or protection of institutions concerned with photographers, as well as “artists who used photography in their work,” a.k.a. the photo-based. In a CVphoto editorial (autumn, 1994), Marcel Blouin insightfully tied specificity to multiplicity, reflecting not just a political attitude, but an accurate view of the movement toward media arts that was challenging the identities (and capabilities) of photographic institutions, even as they were being formed. In light of recent developments (thinly disguised cuts), we are due for another debate over the role of institutions, but I am not proposing to launch that here. What I am interested in examining is the impact of theory on the interpretation of straight photography, the subjugation of subject to photographic effect. To work directly in a medium whose directness is no longer taken for granted – to make pictures about the sensation of directness – has become almost a conceptual project, or so it seems in the work of an artist such as Serge Clément.

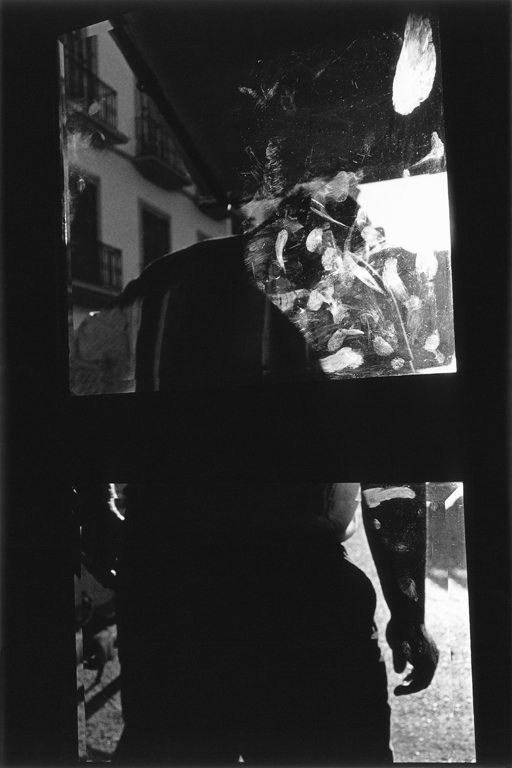

Clément has never, even in his reportage, been a literal photographer, but subject matter has always held some importance, even as the barest reminder – a place-time notation – of the exterior world (Cité fragile, 1992). To find all of that eradicated and replaced by signs of instrumentality (mirror, doorway, or window) and materiality (luminosity, translucence, or grain) is more than the play of abstraction. Jean-Claude Lemagny’s analysis of Clément circa 1996 is a meditation on photographic seeing. It seems to suggest that the act of taking a photograph is really the recognition of photography’s continuous, unshakeable frame. In its anywhere, anytime presence, Clément’s imagery virtually naturalizes the photographic act, not an entirely comfortable notion, though the images themselves are beguiling.

Born in 1950, established during the seventies as a social critic by such series as Affichage et automobile, Clément represents the very type of the Quebec documentarian: engaged and slightly exasperated with the culture (high and low); irrevocably committed to photographic expression. In the eighties, and through to the present, the debate over documentary values has constantly been shifting ground: objectivity or subjectivity; truth or fiction; actuality or abstraction. Of course, it is never at one or the other extreme, but somewhere in between, that we find lucidity, personified by photographers such as Clément, Michel Campeau, and Bertrand Carrière.

The careers of Campeau and Carrière can be compared schematically: both started out in public (social activism, publicity) and gradually, through the eighties, shifted into the private realms of familial and autobiographical expression. In the case of Michel Campeau, an acerbic, sometimes controversial social observer could be seen turning into a romantic as he revisited and reworked the images of his photographic gestation, scraped at his own memories, and turned the camera on intimacy (Les tremblements du coeur, 1988). His memorywork has continued into the nineties, his search now embodied by photographs from his personal archives, through which he is constantly sifting (Ëclipses et Labyrinthes, 1993). From the previous generation, Campeau has inherited a reverence for the book, for visual narrative, and for the close reading of a diary. Carrière, for his part, sharpened his wit by working as a still photographer in the film industry, and by a number of journalistic turns that took him around the world. His love, however, has been invested in a private document, Voyage à domicile, whose very title deflates the myth of the roving photographer, sending him back to his roots in the family album.

The line between exteriority and interiority is a main axis of contemporary Quebec practice. Richard Baillargeon has followed its course as a traveller, in Transit Commedia (1985) and D’Orient (1988–89). Baillargeon is a writer/photographer, productively uneasy with the discipline of a single medium, or with any formulaic restrictions. With Champs/la mer (1994), chasmic spaces opened up in his work: the horizon seemed not quite far enough away. He translates this restlessness into words, images, the flickering cinematic screen that will not rest in the photographic present (De plus loin: l’onde, 1995).

Inside/outsider: for all its transparentness, Clara Gutsche’s documentary project on nuns negotiates that line, as France Gascon explains in Clara Gutsche: La Série des Couvents (1999). Gustche has been photographing Quebec for most of her adult life. Since the seventies, projects on architectural heritage have alternated with studies of neighbourhoods and families, most recently her own (Sarah, 1982–89). Still, she sees the culture from outside. The influence of Catholicism is something that intrigued her; she began with the architecture of religious communities, but she was moving irrevocably toward the women themselves, who present, within the rules of their order, their spirituality and sisterhood. The cloister is real; it is also the perfect metaphor for the documentary frame, the proto-archive.

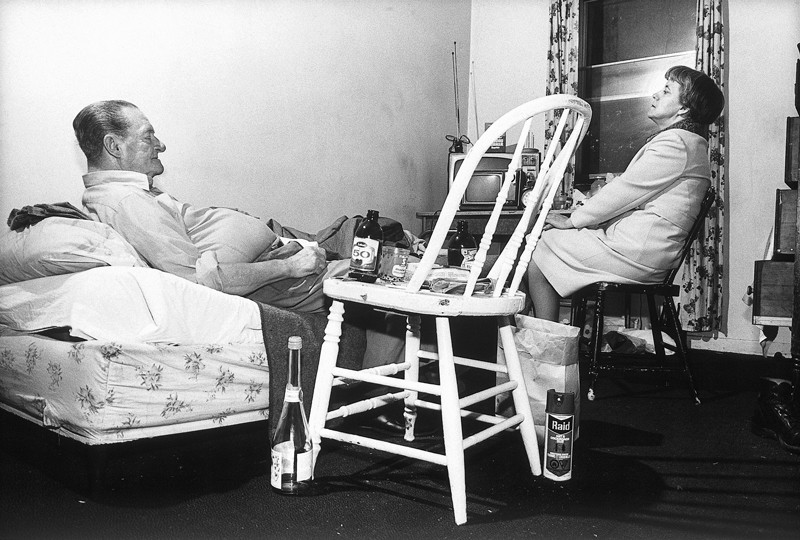

To build an archive from the disorder of actuality involves considerable perseverance – some would say, verging on obsession. Both of these descriptions fit Donigan Cumming and Robert Del Tredici, though the issues that they have addressed and the results of their projects are light-years apart. Cumming launched his attack on the formulas and facile reception of social documentary photography with Reality and Motive in Documentary Photography (1986), a three-part cycle of images and sound for which he recruited mostly amateur models to play versions of themselves as types. The hyper-realism and absurdity of his approach, maddeningly discordant in The Stage (1991) and intimately focused on Nettie Harris in Pretty Ribbons (1993), were exacerbated – strange to say – by the facts. For if Cumming had created his community by device, it nevertheless existed by the early nineties, its members familiar, the elders beginning to disappear. The stories of the community would blend in the fictions and actualities of his videotapes and multi-media installations.

Robert Del Tredici, for his part, set out to document, though not necessarily to preserve, the international community of nuclear defence and industrial power. Del Tredici can easily be understood as a vigilant and vexatious reporter, however neutral and open to his subjects, always on the outside looking in. At Work in the Fields of the Bomb (1987) is not a polemic, but the alarm of its author is unmistakable. How surprising, then, to find Del Tredici’s investigative photographs put to use in a document of official United States policy, Closing the Circle on the Splitting of the Atom: The Environmental Legacy of Nuclear Weapons Production in the United States and What the Department of Energy Is Doing about It (1995). This is a book of photographs with provocative captions – Del Tredici’s throughout – printed in an edition of 100,000 copies, an extraordinary landing for this radical archive.

The whole notion of the archive can be seen to have exploded over the last fifteen years. Foucault-type dissections of knowledge are far from the last word. Instead, the appropriation of the imagery and objects of scientific inquiry and organization have fused with projects of feminine identity, and other lines have been drawn, between history and memory, memory and the body, the body and the archive. The work of Nicole Jolicoeur can be found at the centre, her excavation of Charcot’s nineteenth-century hysteric – the female body – translated to an exotic site and figured in her own surrender to place, the French city of Annecy. The Annecy commission, exhibited on site and at Galerie de l’UQAM, was a departure for Jolicoeur, and an illumination for her audience. Perhaps only now can we fully appreciate her equivocal relationship to the Charcot archive as a theatre of science and subjugation, as well as a revelatory experience of the female mind and body.

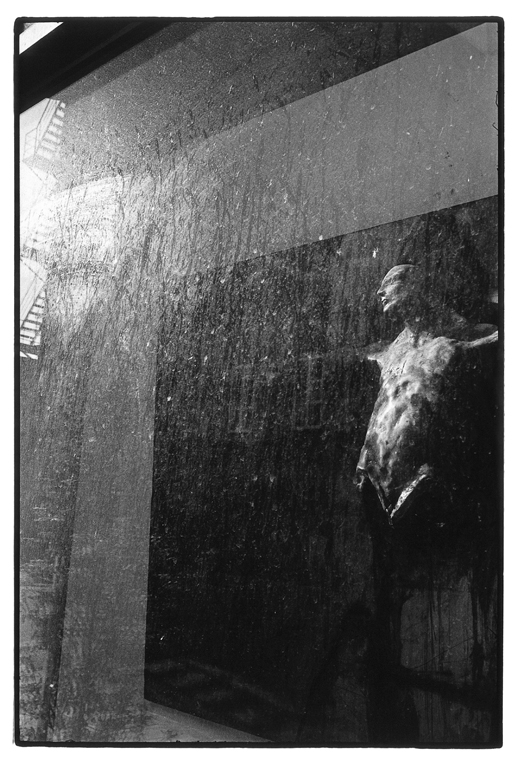

Something similar was at work in Angela Grauerholz’s 1995 solo exhibition at the Musée d’art contemporain. Grauerholz’s monumental pictorialism filled the galleries with its dreamy effects, the interplay of visual knowledge and irrational unrest their continuous thread. The curiosity in all of this was a monolithic presence, Eglogue or Filling the Landscape, Grauerholz’s “personal archive or a museum of landscape photographs,” a design object containing labelled boxes of prints that were shown to the public by a member of the museum staff wearing white gloves. The anti-display was part of a trilogy that Grauerholz had begun at the Domaine de Kerguéhennec in Brittany, where she had illustrated the mental decline of a fictional character through her progressive abstraction of the landscape, a series of images permanently installed in the drawers of the castle’s library and dedicated to women artists and writers who had taken their own lives. “Aporia” is an impasse of a different sort, a creative passage that does not yield quickly to understanding. Aporia: A Book of Landscapes, published by the Oakville Galleries, contains the landscape photographs that in Montreal were encased, thus preserved and protected from view.

The landscape has made an interesting transition from the eighties to the nineties, framing questions of philosophy and pleasure in terms unthinkable fifteen years ago. Nature has gone from a signifying element, squared in the viewfinder of culture, to an organic, regenerative experience shared through the imagination. I am thinking here of Serge Tousignant’s steady movement (1970s-1990s) from the corner of the studio through the sun drawings to the garden, but there are other examples. Lucie Lefebvre’s early still-life fabrications made fun of illusionism, effectively cutting the cord to nature; her current approach is more subtly artificial, closer to natural form. Sylvie Readman made sites of outdoor exploration from photographic fragments of banal interiors landscapes (Chambre, 1989). She went on to review the landscape through nineteenth-century screens of cultural convention, painting and photography (Petite histoire des ombres, 1991). She has since immersed herself in a plein-air photography that expresses the dialogue between visual habit and intuition (Reviviscence, 1995). Denis Farley, too, is constantly referring to nature as he retraces the scientific models of vision that we find so natural today.

As it always has, and will, our conception of nature has changed. Consider the work of Roberto Pellegrinuzzi. In the eighties, the idea of photographic landscape loomed large in his work, always commenting on its own presence, on the simulacrum, on the problems of representation. When, in 1990, Pellegrinuzzi began to concentrate on one natural integer, the leaf, he was not abandoning the mediating structures of language, architecture, and instrumentality that had brought him there, but he was certainly adding a level of intimacy and, dare I say, spirituality to his discourse. Sylvie Parent’s essay in Roberto Pellegrinuzzi: Le Chasseur d’images (1989–94) is perfectly matched to the artist in terms of intelligent, economical analysis, but I disagree with her on one point. She speaks of a sense of loss (the shadow of photography on the work), but I cannot feel it. Pellegrinuzzi’s fascination with and facture of the photographic object is highly sympathetic to the processes of nature, and when I see that the emblem leaf has been replaced by the emblem skin, I know that I am right (40 Instants, 1998).

To discuss this period without reference to the body or the computer, one would have to be a virtual Luddite. Summon the body with its scars and underground rivers – look at it, hear it – and you have the sensorial experience of Geneviève Cadieux. As Johanne Lamoureux observed in 1991, Cadieux’s invitation of the gaze onto a fragmented female body has sometimes verged on the fetishistic – perhaps those lips that advertise the femininity of the Musée d’art contemporain are what she had in mind. But the scar, Lamoureux continued, is an opening to language. Now it is the interior of the body – its streams of memory and their vocal tributaries – that Cadieux wants poetically to evoke (Tears, 1995).

Photography is now inflected with a certain degree of nostalgia. Photographic technology has been surpassed and redeemed, its association with more frightening technologies set aside, and a certain gloom lifted in the process. Situated in relation to late nineteenth-century Technology (friendly or alien), the camera is back to its quasi-human role. If Marie-Jeanne Musiol uses the Kirlian apparatus to reveal invisible natural forces, what glows in the dark is recognizable as a leaf (Feuille de violette, 1996) and beautifully (reassuringly) close to Talbot’s early-nineteenth-century experiments.

The dematerialized image no longer symbolizes fear of our own dematerialization, but some excitement over the possibilities, and no small confidence that whatever we blow away (virtually) can be put back together. Even in the eighties, it was obvious that Alain Paiement really liked technology. If, as Barbara Fischer explained in relation to Amphitheatres (1989), Paiement was interested in visual systems, his insistence on “the individual’s perception and cognition” leaked some of the enthusiasm and showmanship that Sometimes Square (1994) poured on. I will be accused of art-historicizing, I’m sure, but Paiement’s construction impresses me with all the world-making ambitions of a nineteenth-century diorama; the genius of the site – a creature of American heritage, kitsch, illusion, disillusion, and greed – wants to co-sign the piece and that jostling is all part of its fame, the buzz.

Certainly, technology can be more discreet. Ginette Bouchard conflates digital technologies with pictorialist materials, such as palladium or platinum (Floris Umbra, 1995). Bouchard serves as the perfect illustration of the argument that computer technology has added very little that is new, but simply facilitated image-making in ways of which William Notman would have approved. Too perfect, for one would expect this from an artist who has been composing and experimenting with materials as a committed printmaker from the beginning. The garden that Bouchard has been cultivating has always been romantic by design – voluptuous, melancholic, and dotted with ruins.

Holly King’s Landscapes of the Imagination share some of these characteristics. They are constructions: they were originally three-dimensional models, destined solely for the camera, some formed in clay. These were landscapes or seascapes whose jagged or roiled surfaces seemed fraught with novelistic disaster. The colours that she introduced later were not natural, and the vegetation seemed odd, possibly overdosed with whatever was turning the water and the air colours (Tundra Divided, 1990). King’s work in the early nineties was often equivocal, its pleasures and terrors in the vein of the sublime, full of contrasts between seductive and forbidding zones. The loss of King’s second daughter, Olivia Rose, is marked by works of mourning and memory, still-lifes replete with symbolic associations so gently, so tenderly articulated; King would not want us to feel the pain that she feels. The equivalence she draws is with the beauty of Olivia Rose, her continuous presence among the living (Rose Remembered, 1995).

Each of the important retrospectives of the period (among them Evergon, Charles Gagnon, Tom Gibson, Gabor Szilasi, Serge Tousignant) was in some way transformative, but these passages are beyond the scope of this article. We are concerned here with instances of redefinition. Michel Lamothe’s very modest exhibition of 1995 was just such an occasion – the time is coming when I will say so again.

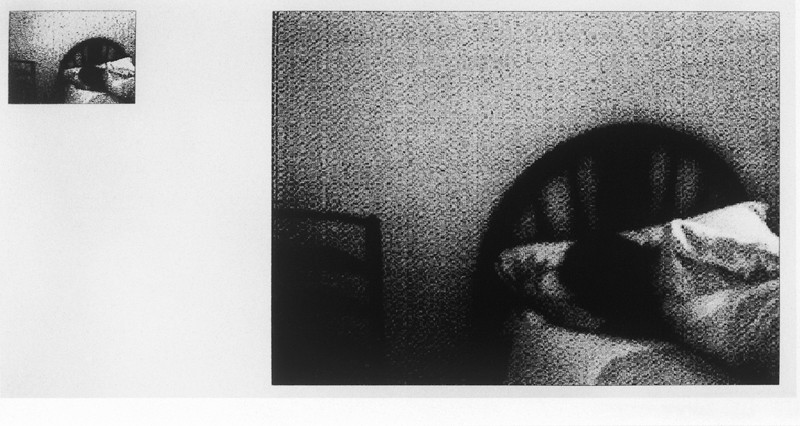

In this medium of greys and soft, temporal transitions, the perception of change can be very subtle and rewarding. What does it mean in the work of Raymonde April? If we stop for a moment and think about the April of the seventies, she is inseparable from the decade’s great passion for photographic narrative, the marriage of image and text. Since then, we have watched April’s stories dissolve into portraits, still-lifes, and landscapes that led the imagination into a world of metonymic objects (Trois histoires affamées, 1988). Her mood has become calmer, more confident, so that the centrepiece of Les Fleuves invisibles is a group of thirty-three images that extols the virtues of waiting and watching (L’Arrivée des figurants, 1997). Sometimes, nothing seems to be happening, then a figure dives into the void.

In his catalogue essay for April’s Réservoirs Soupirs: Photographies 1986–1992, Gaëtan Gosselin noted that she had gone through a critical phase in her development while working in Paris in 1989. Her work had taken shape in what he called families of images, meaning series or multiple-image works by association. In Les Fleuves invisibles, Nicole Gingras took another tiny step, announcing that after twenty years, April’s entire oeuvre comprised “a family of images.” April is evolving as she should; there is something very appealing about her steadiness and restraint. We would not want her to change course, to deny us access to those latent images. Perhaps the church mothers will intervene. Perhaps April will indulge us until 2033.

Martha Langford was the founding director of the Canadian Museum of Contemporary Photography (1985–1994); she is currently a post-doctoral fellow at Simon Fraser University (Vancouver). She has organized a number of exhibitions, including Anima Mundi: Still Life in Britain (1989), George Steeves: Excavations (1991), Tom Gibson: False Evidence Appearing Real (1993), and On Space, Memory and Metaphor: The Landscape in Photographic Reprise (1997), all presented in MOIS DE LA PHOTO À MONTRÉAL. Author of numerous books and catalogues, Langford’s articles have appeared in Exposure, Creative Camera, Blackflash, JAISA, CVphoto, History of Photography, and Border Crossings.