[Winter 2001-2002]

by Robin Metcalfe

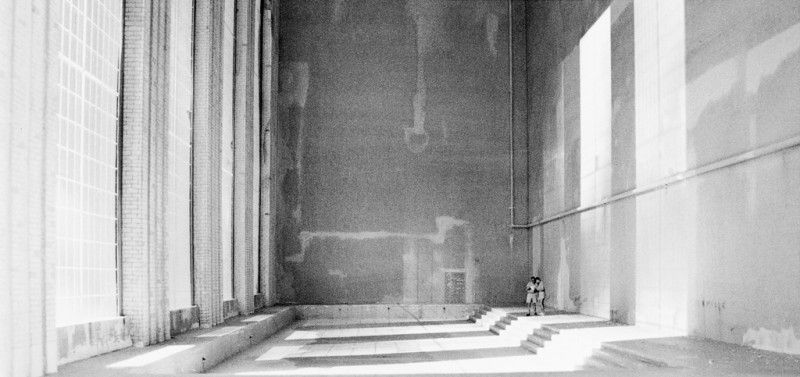

For those familiar with Carl Zimmerman’s work, there was a moment of déja vu when the first photographs of England’s new Tate Modern appeared.

Housed in the refurbished Bankside Power Station, the gallery’s massive Turbine Hall looked for all the world like one of Zimmerman’s sublime, imaginary interiors. An actual image from Zimmerman’s Landmarks of Industrial Britain appeared in the May 2000 C Magazine on the same page as a photo of the Tate, inviting direct comparisons and double-takes.

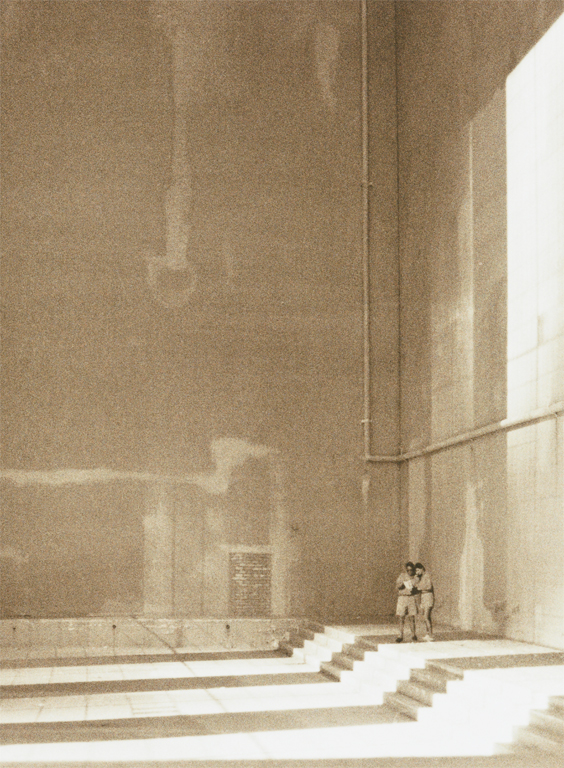

For his Lost Hamilton Landmarks series, first exhibited in 1997, Zimmerman shot on black-and-white film and printed through commercial colour process, resulting in sepia- and cyan-like effects that invite nostalgic associations with earlier photographic technologies. They appear, quite convincingly, to be documentary photographs of huge industrial and institutional buildings from the first half of the twentieth century, now derelict and showing signs of age, such as chemical staining on their vast concrete surfaces. In fact – and this is the not-really-secret key to Zimmerman’s project – the artist photographs maquettes that he builds in the small Cape Breton home that he shares with his family and several animals. The maquettes evolved as a by-product of another visual art practice, studies for the artist’s site-specific installations, which involve the selective introduction of light, sound, paint, and objects into existing spaces.

All the trickery in the Hamilton series is achieved by old-fashioned handcraft, in the painting and lighting of the maquettes’ surfaces. Only in the more recent Industrial Britain series has the artist begun, with a shift to large-scale ink-jet printing, to explore digital effects. This allows him to edit the images that he still generates through the meticulous construction of maquettes.

Zimmerman attributes to his photographs “an essentially utopian aesthetic with ambivalent understandings.” Humour, nostalgia, and critical deconstruction coexist in his work, as they often do in our responses to totalitarian aesthetics. “Fascinating fascism” shares its allure with the less radically discredited, but equally utopian, architectures of socialism and New Deal social democracy.

Whereas the Hamilton series drew on personal memories of the Ontario city where the artist grew up, Landmarks of Industrial Britain imaginatively inhabits a country in which Zimmerman has no personal history. It was in nineteenth-century Britain that the utopian dreams of Enlightenment rationalism first began to transform the landscape at large. Unlike the gardens of Versailles – whose vast terrain was essentially contained, excluding all signs of the labour that sustained its luxurious display of wealth – the great structures of Victorian England were inclusive, extending their imperial force over the entire landscape and population. Queen Victoria shared the 1,800-foot-long Crystal Palace with her middle- and working-class subjects.

Zimmerman extends certain tendencies within nineteenth-century British architecture by imagining a “state-sponsored school of public architecture” such as one might have seen had Marx been right and England the first home of a revolutionary proletarian (or even Fabian socialist) state. There is a contradiction between this socialist utopianism and the stupendous architecture in which Zimmerman proposes to house it. It is the contradiction at the heart of utopian socialism and of the choice, by the English-speaking countries during the Victorian era, of authoritarian architectural models (notably that of imperial Rome) for their increasingly democratized societies. In their public buildings, England and the United States had favoured an architecture that subjugated both the environment and its tiny human inhabitants to its own overwhelming grandness, demanding a response of speechless awe.

In its Romantic search for novelty and sensation, British architecture from the late eighteenth century on ransacked every available architectural vocabulary, from the Hindu to the Gothic. This eclectic mix included neo-classicism but rejected the classical ideals of restraint and balance in favour of the inchoate and excessive emotional states of the sublime.

The eighteenth-century French architect Étienne-Louis Boullée had dreamed, in his Project for a Memorial to Isaac Newton (1784), of a pure architectural geometry executed in traditional stone compression architecture. Victorian British engineers made the radical leap to a practical geometry of steel-frame construction, most evident in functional and quotidian structures such as bridges, railway stations, and temporary exhibition halls. Despite the unprecedented lightness of the new steel-frame structures, they and the architecture of reinforced concrete tended toward an aesthetics of power rather than of grace.

In Great Hall, Civic Mausoleum, Birmingham, England, a metal stairway appended to the left-hand wall establishes its gargantuan scale and also demonstrates Zimmerman’s wry humour. This stairway to nowhere – rather like the celebrated 10-metre spiral staircases topped with mirrors in the Tate’s Turbine Hall – occupies a ceremonial space with no conceivable practical use other than as a zeppelin hangar. It gives a further twist to the artist’s sly joke of creating these persuasive yet impossible spaces. Together with the scaffolding and silhouetted figures visible farther to the left, it recalls the workmen seen passing in the background of the Fascist party headquarters in Bertolucci’s 1969 film The Conformist. Bertolucci’s tiny humans are carrying, and dwarfed by, giant pieces of authoritarian sculpture – which, on reflection, would be far too heavy to bear unless they were objects of stage artifice, constructed from light, flimsy materials. The man behind the curtain (to shift film references to The Wizard of Oz) is never completely hidden in Zimmerman’s work, and yet we are all too willing to pay him no attention, wanting to be persuaded by his intimidating spectacle.

Zimmerman calls his images “portraits” in contradistinction to a factual record. While allowing that they are fictional constructions, the term nevertheless suggests that they be read with reference to actual built environments. This suggestion is further emphasized by the use of real place names in their titles, such as Hamilton, Birmingham, and Manchester, cities iconographically associated with large-scale industrialism in their respective countries.

Among the photographs’ specific references are ones to the Crystal Palace (in Great Hall, Civic Mausoleum), to the Basilica of Constantine and its many railway-station imitators (such as Toronto’s Union Station), and to the dome of the Hagia Sophia – whose four supporting arches reappear in Public Baths, Manchester, England. The minimalist severity evident in the exterior of Mausoleum, Birmingham, England recalls that monument of high modernism, Mies Van Der Rohe’s Barcelona Pavilion, with its horizontal planes of dressed stone. Zimmerman, whose Rotunda, First United Church in the Hamilton series quoted the dome of the Pantheon to great effect, returns to that classical form in Museum, complete with a fallen column fragment being inspected by a microscopic visitor.

The geometric simplicity of the circle and semi-circle characterized the great public buildings of Sir Edwin Luytens. The British architect’s last major commission, never completed, was for a Roman Catholic cathedral in Liverpool (1930–39) that would have been twice the size of St Peter’s. Zimmerman’s maquette for a giant Pump House echoes the horizontal courses of warm, light-coloured sandstone in Luytens’s Viceroy’s House in New Delhi (1923–31), which covers an area equal to that of the palace at Versailles.

The cult of the stupendous is still with us, however traumatized by the events of September 11. However, the defining architectures of our age – the shopping mall, the airport terminal, the theme park – are increasingly characterized by a chameleon-like invisibility that collapses into incoherence. In themselves, they are cheap and utilitarian sheds, boxily plain or buried beneath commercial signage. An architectural moment – an atrium or a view of the sky – appears out of nowhere, as if on a revolving stage, then vanishes again in a Babel of competing boutiques. These halls of mirrors are labyrinths of consumer yearning, theatrical warehouses for the staging of effects. They project an ever-changing kaleidoscope of utopian desire without embodying any idealized single form.

Paradoxically, our emerging totalitarian consumer state has largely renounced authoritarian architectural effects as Western societies become less democratic and more ubiquitously policed by the decentred eye of the security camera and the magnetic code. Zimmerman’s utopian architectures recall the last historical moment in which collective ambitions were legibly embodied in built form.

Carl Zimmerman studied briefly at the Nova Scotia College of Art and Design and McMaster University. His installation and photo-based work has been exhibited nationally and internationally, with recent solo shows at the Art Gallery of Hamilton, St. Mary’s University Art Gallery, Halifax, and the Owens Gallery, Sackville, N.B. He is currently an artist-in-residence at the Irish Museum of Modern Art in Dublin, Ireland.

Robin Metcalfe was recently appointed Curator of Contemporary Art at Museum London in London, Ontario. He is the author of The Utopian Architectures of Carl Zimmerman (1997) and of a recent essay, “Aerial View,” that considers the specular relations between the skyscraper and the airplane. This is the second time he has written for CV Photo.