[Summer 2002]

National Gallery of Canada

February 1 to May 12, 2002

No Man’s Land: The Photographs of Lynne Cohen, was organized by the National Gallery of Canada, in collaboration with the Musée de l’Élysée, Lausanne. It was shown at the National Gallery of Canada, from February 1 to May 12, 2002, and is now touring extensively. It is accompanied by a publication of 160 pages, published by Thames & Hudson, London. A French version was also published by Thames & Hudson, Paris. See review in CVphoto, no. 56.

In the photographed world according to Lynne Cohen, the places that we are least familiar with are those in which we spend the most time. In looking closely at constructed spaces for work and rest, Cohen reveals how strange these places can be. Countless waking hours are devoted to work, and yet how often do we stop to scrutinize the rooms in which we spend our days or, for that matter, the corridors we pass through on the way to the office? We have constructed a complex landscape of places and spaces to be in, but we hardly give them a second thought after their initial design, layout, and outfitting. Furthermore, we seldom question what these spatial configurations tell us about how we live.

The topography of the home is determined by the activities or objects that dominate each room. The bedroom, for example, is charted out in this way. According to this mapping practice, however, the most curious of rooms in a house is the “living room,” because its designation suggests that the very process of being alive transpires inside this room. What does this mean? Furthermore, how do you adequately furnish this space for such a task as living? And what happens when you leave the room?

The living room functions as a “public” space within the private sphere of the home, as invited guests are permitted to spend time there. For these occasional encroachments, the living room is kept neat and clean, like a showroom for best behaviour, style, and tastes. Likewise, the spaces designed for the activities of work represent a curious interlacing of function and form, in that desires for graceful surroundings are outweighed by operational necessities. Thus, even if the work environment is elegantly appointed and tastefully furnished, it remains a place of business and nothing else, irrespective of how much time is spent there during the day or night, and regardless of the importance of work to one’s identity. Offices are not living rooms, but they do share some of their attributes. They serve as the physical manifestation of one’s working life. Moreover, unless the room’s occupant receives a promotion or vacates the space, office furnishings and configurations are rarely altered. The prevailing sense of suspended animation in these rooms further augments their already strange characteristics.

Cohen has been exploring photographically such simultaneously foreign and familiar environments for more than thirty years. She trained as a sculptor and printmaker, but turned to photography in the early 1970s as a means to capture the qualities of interiors that she found so compelling. Akin to the traditions of documentary photography but a clear departure from its aims, Cohen’s photographs can be read as cautionary tales of societal conditions. At times, in addition to their sinister overtones, her photographs are also very funny – like paranoia balanced with a healthy sense of humour. Part social anthropology and part stakeout, the interiors framed by Cohen’s lens are incredible, in the sense that they appear almost too strange to be believed. And yet they are all too familiar – as though recognizable from science fiction or dreams or, worse, from our very own waking, living, and working lives.

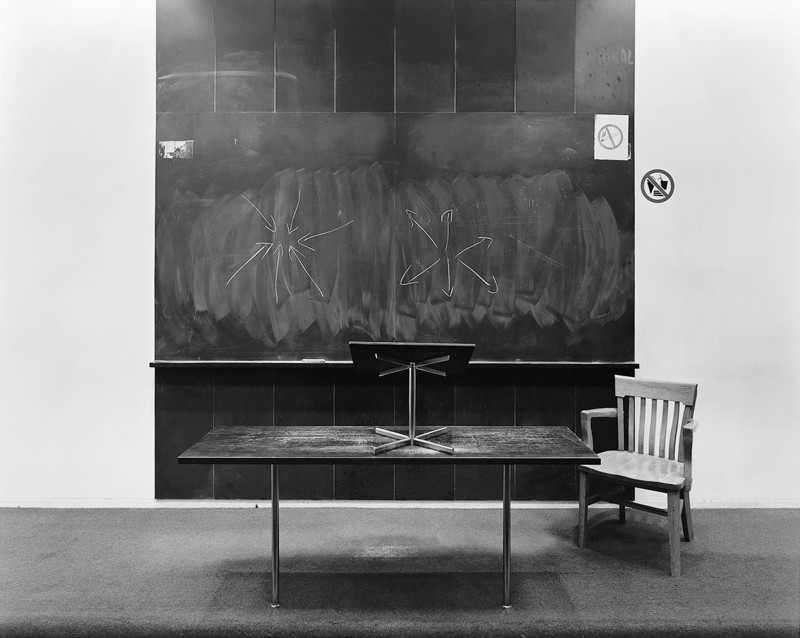

No Man’s Land: The Photographs of Lynne Cohen, organized by Ann Thomas, curator of photographs at the National Gallery of Canada, is a retrospective drawing from the full scope of Cohen’s photographic series in both black and white and colour. The exhibition chronicles Cohen’s careful explorations of interiors that intrigue her, recording those places that get under her skin and obsess her. Cohen offers these glimpses to the viewer in carefully composed images that seem detached, but clearly not disinterested. Many of her observations translate into photographs of quite commonplace terrain, such as lobbies or offices, while others carry the whiff of restricted or privileged access, such as military installations, laboratories, and spas. All of her photographs are titled with consciously utilitarian identifiers, according to the interior’s broad category: Spa, Observation Room, Classroom. At play in Cohen’s naming strategy is the relationship between similarities and differences made apparent by the categorization of space, as it is only through multiple views of analogous rooms that one begins to notice the patterns that emerge in these environments.

One of the unifying characteristics of Cohen’s body of work is the deliberate presence of absence. In spite of all the evidence suggesting that people inhabit or work in the spaces that she explores, Cohen’s compositions depict them as completely deserted, as though everyone had vanished. The visual negation of life prompts the viewer to question whether these spaces are real or, perhaps, constructed sets. In an interview appearing in the exhibition’s catalogue, Cohen acknowledges that she does move objects out of the composition if their presence distracts, but aside from such minor adjustments, the field of the resulting frame is as she found it. Her admission should reassure, but instead it perplexes. It implies that the everyday and ordinary need only be examined with a more careful eye to uncover something abnormal just below the surface.

No Man’s Land provides the viewer with the rare opportunity to experience the radical shift in Cohen’s work from contact prints to the large-scale enlargements for which she is best known. The smaller photographs have a quirky edge to them that is recast as something altogether menacing in the larger works. Interestingly, the shift to enlarged views corresponds with Cohen’s abandonment of domestic spaces as subject matter in favour of images of military classrooms, police academies, and laboratories. The change in scale not only functions as a means to draw attention to the fascinating details within these environments, but also creates a stronger sense of drama alongside her critical interrogation. The large-format photographs should seem more “real” to the viewer, as the size of the objects depicted therein is closer to reality, but paradoxically these compositions provoke the strongest sensations of artificiality. The strong visual presence of these photographs is heightened by Cohen’s use of Formica frames, which serve as sculptural and tactile references, imbuing the resulting work with a three-dimensional quality. Cohen selected the plastic laminate for her frames because its decorative elements are produced through photo-reproduction. Formica is the ultimate fake substance, with its claims to being even better than the real thing. The product’s echoed wood, leather, granite, and multitude of colour permutations attach another critical layer to Cohen’s consideration of the fabrication and simulation intrinsic to the spaces we design for work and play.

In the last four years, Cohen has begun to work in colour, while continuing to photograph in black and white. Prior to this period, she had considered colour to be extraneous to her project, as it added little to the photograph to know whether or not the tiles on the classroom floor were white or peach. What changed? For Cohen, it was the realization that she could explore the viewer’s inappropriate expectations that colour photographs are in some way closer to reality than black and white. The colour in Cohen’s photographs is troubling, like loud visual noise. It deceives and creates a further layer of distance between the viewer and the photograph. The blues of the spa bathwater ooze a livid turquoise, as if the pool were filled with a gelatinous substance that would smother rather than soothe. The hard, white surfaces gleam as though they were radioactive.

While on view at the National Gallery, the works in the exhibition were installed at a lower height than expected on white walls with the labels discreetly positioned far away from the photographs. The viewer was free to roam visually through the photographs without distraction. The hanging height of the photographs corresponds to Cohen’s preferred vantage point when positioning the shots, so that the viewer could likewise look down and into the picture-plane. These curatorial choices were due in large part to consultation and collaboration with the artist, and there is a freshness to this approach.

No Man’s Land proposes a vantage point onto Cohen’s potently unified and technically strong body of work. Cohen’s gaze has been unwavering and clear for over three decades, and her observations are always insightful, if somewhat disturbing. Her photographs unpack the familiar and transform it into new terrain for observation. In opposition to déjà vu, Cohen’s photographs arouse a feeling of jamais vu — an unsettling lack of familiarity with the everyday. Moreover, the succession of emptied, silent spaces provides the viewer with the sense, both intoxicating and somewhat frightening, of accessing the known unknown. We see these interiors in a way that nobody else does, with the freedom gained through private admission to public and not-so-public places. Cohen’s photographs confirm what we might secretly or outrightly believe about science and the military, that strange things take place behind closed doors. Yet Cohen also reminds us to look closely at other, more benign environments. These are equally curious places. Bare expanses of linoleum will never be the same after seeing them through Cohen’s lens; neither will shag carpeting or Formica. Nothing is quite as it seems. But it is.

Johanna Mizgala has worked as a freelance curator and is a regular contributor to visual arts periodicals. Her research interests include memory and identity in relationship to contemporary photography and photo-based art. She was recently appointed to the position of curator of exhibitions for the development of the Portrait Gallery of Canada, an initiative of the National Archives of Canada.