[Summer 2004]

The objects photographed and recontextualized document social aspects of the everyday and over-consumption. They tell a kind of personal and social history of the actions and rituals performed on a daily basis in a world of consumption.

by George Bogardi

Nil posse creari de nib.

— Lucretius

1. Louis Joncas has been working on this immense series of still-lifes for over a decade now; as of 2004 there are more than a hundred of them.

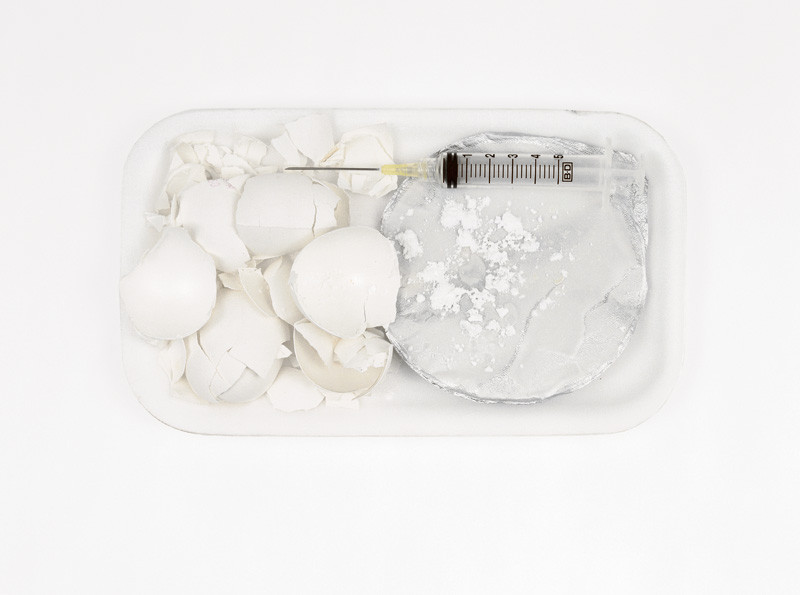

Their title, Detritus, is by no means a metaphor. The photographs are built out of the most humble subject matter: they depict things that we routinely throw away without a glance, without a thought.

These scraps have already served their purpose, so their presence now is just an annoyance – they will have to be thrown away for the sake of hygiene and aesthetics. Not even the most desperate aspirer to a place in the Guinness Book of Records would dream of making a collection of this stuff.

2. Of course, humble objects have always been the principal components of the still-life. Always low in the hierarchy of artistic genres because it does not tackle the grand themes of Nature and Spirit and History – does not tackle, in fact, much of anything worth a capital (or, simply, capital?) – it is still-life, or nature morte, because its subject is inanimate, unspirited, dumb.

In Looking at the Overlooked, his book of essays on the still-life genre, Norman Bryson coins the term rhopography; “Rhopography (from rhopos, trivial objects, small wares, trifles) is the depiction of those things which lack importance, the unassuming material base of life that ‘importance’ constantly overlooks.”

3. The trifles that Joncas focuses on are the household scraps left over at the end of the day: crusts and husks and bits of food that are all visibly mouldering even as the camera is rendering them “immortal.” The great still-lifes of the past, almost without exception, depict fruits and flowers at the peak of glowing perfection: it is thus we see them in Zurbarân and Chardin, in Manet and Fantin-Latour, in Irving Penn. Even Goya, usually so inclined to caricature, paints ham and salmon that would tempt an anorexic. Joncas’s kitchen sweepings are like a realist’s rebuke to those masters.

4. Two other categories of rhopos are shown time and time again in Detritus. One is a range of products – or, by now, by-products – of consumption: foodstuffs still, but also empty packaging, cigarette butts, used condoms, and a somewhat sinister number of empty vials and other medical paraphernalia – all the debris sloughed off by the human organism in quest of pleasure or solace.

And then there is material depicted here that is even more abject: dust and lint, and crumbs and stains, an accumulation of stuff that does not even have the dignity of having been associated with anything pleasurable or useful or meaningful. These things are material signifiers, though just barely. They are formless, on the brink of losing their place in the material world, barely substantial enough to be represented as imagery.

5. Irving Penn, too, has photographed cigarette butts and other such lowly material. But he is a decorative formalist, while Joncas is a realist-moralist. In Penn, the trivial object – a crumpled cigarette pack, say – is lifted out of context (“rescued from the gutter” literally and figuratively) and placed against a pristine, seamless background. Exquisite framing and lighting and printing with distillates of precious metals transform the dowdy thing into a ravishing phenomenon. This is the decorative impulse of fashion photography at its purest: a celebration of shape over mass, form over meaning and pragmatics.

6. “My works are self-conscious reflections on the Vanitas genre,” Joncas writes in an artist’s statement. While the still-life has historically occupied a low place in the hierarchy of artistic genres, it has often aspired to a spiritual and not just purely documentary role. If the old masters depicted the cornucopia of earth’s bounty at the very peak of bloom, it was to remind us that from this acme of perfection the road leads only one way: down the slope of decay.

Time means change, the vanitas reminds us, and change can only mean decline. Just to make sure that this threat is driven home, these images never fail to include among the splendid fruits and flowers a grinning skull or an hourglass: unsubtle, even coercive as teaching tools, but effective.

7. Joncas adapts the traditional genre to modern circumstances. His audience, he seems quite aware, is young, urban, and restless, accustomed to thinking of spiritual nourishment in terms of entertainment, and therefore resistant to the persuasive techniques of the lecture and the sermon. The new sensibility is likely much more preoccupied with this world than the next, hence more responsive to themes of illness than to the challenge of death.

8. “Removal of the human body is the founding move of still life,” Bryson notes. But in Detritus the human body is constantly evoked, we see its extensions in the gestures of hands, objects on a platter, or the sculpting of lint into delicate, heroic masses – an absurd game worthy of Molloy.

And we can reconstitute the human body – as an organism – in picture after picture, voraciously consuming and being consumed by sedatives and stimulants and a torrent of other arcane substances; a close reading of these images would require the assistance of someone with a medical degree.

Skills in anthropology and the semiotics of marketing would be useful as well. “Dis-moi ce que tu manges, je te dirai ce que tu es” is an inevitable subtext in these photographs, updated to suit the consumer culture of c. 2000 A.D, as “Show me your brands…”

9. The “consumer profile” is quite clear here, as is the presence of the body behind it. But there is another presence to be discerned here as well: that of a self accompanying the organism. It is this last aspect – spiritual? moral? sentimental? The choice is entirely up the reader – that raises Joncas’s still-lifes into the realm of vanitas.

It’s not that the pictures moralize, not at all. But given the strong juxtaposition of sexual paraphernalia with pharmaceuticals, it is hard in the age of AIDS to see these photos and not be set off on a chain of associations that will lead back to those old motifs: the hourglass and the skull. The emotive charge here is very strong, even if unnamed. Repentance? Rage? Laughter in the dark? There is a phrase in Genet’s Querelle: “Ces humeurs bouleversantes, le sang, le sperme et les larmes.”

10. But these are pictures. Before and after the lessons are read, these photographs assert themselves as a brave new breed of still-life: part vanitas, part billboard. It’s not as unnatural a pairing as one might first think. “The final reason for the need to photograph everything,” Sontag writes in On Photography, “lies in the very logic of consumption itself. To consume means to burn, to use up – and, therefore, to need to be replenished.” There is the connection and the difference: in the realm of the traditional vanitas, replenishment is a spiritual process; in the realm of advertising, it is a need, satisfied by consuming some more.

“The possession of a camera,” says Sontag, “can inspire something akin to lust.” No need to belabour the point: contemplation of images can also inspire desire – a longing for more that is as potent as it is promiscuous. The advertising industry stakes its fortune on this. In Detritus, Joncas deploys the full arsenal of photographic seduction used in advertising: the images are as large and glossy as billboards; the debris of daily life is gathered into compositions just tight enough to suggest something exclusive and enticing, and just loose enough to promise something attainable.

This kind of ambiguity, the fundamental technique of all the different arts of seduction, is a cornerstone of both art and advertising. “L’art publicitaire,” notes Baudrillard in La société de consommation, “consiste surtout en l’invention d’exposés persuasifs qui ne soient ni vrais ni faux.” Nor does the ethos of art require anything more than a convenient fabrication. So when Joncas trains his camera on a wisp of debris – a handful of fluff and dust, nothing really – and frames it just right, we are seduced into believing that this is indeed something, something beautiful and desirable, capable of providing us with our daily minimum requirement of meaning.

For more than ten years, Louis Joncas’s work has been concerned with still-lifes, vanitas, and detritus. Joncas has exhibited his work mostly in eastern Canada, but also in Louisiana and France, and he is represented in institutional and private collections. Born in Winnipeg in 1959, Louis Joncas lives and works in Montreal. He is represented by Pierre-François Ouellette Art Contemporain.

George Bogardi is an artist and critic. He lectures at Concordia University, Montreal.