[Summer 2005]

Optica Centre for Contemporary Arts, Montréal

March 5 to April 9, 2005

There has always been a quiet elegance to Karen Henderson’s works. The artist, generally working with photo-based installations, is interested in the creation of carefully executed, labour-intensive works, in which consideration of the materials used moves beyond the object itself and spills over into the orchestration of gallery space and viewers as artistic components. This, along with simplicity of subject matter and minimal intervention with the work’s materials, helps to create an atmosphere of expectant emptiness where anything is possible – or nothing at all.

The gallery space as a “white cube” provides the conceptual context for the work. In the 1960s and 1970s, innovations such as the invention of acrylic paint and the commercialization of video cameras gave artists the opportunity – and the inspiration – to describe the creative process as the subject of their work. Galleries were constructed to house large-scale action paintings or murals reduced to minimal sculptural elements and time-based projections. The gallery space became both a vehicle and a muse for artists. Henderson continues to work with the ideas developed in conceptual art practice, with a haunting belief that experiences and participation within the gallery space can create unique perceptions of our relationship with space and objects. The artist talks about her work as a kind of documentation in photography, film, and video:

I usually document the gallery itself, which I think complicates the viewing experience, shifting it towards an area of experimentation by collapsing where you are and what you’re seeing into the same thing. It means that the subject of the work can be about being there and looking at that work, which in turn represents where you are and implies the looking at the work part. In this way, I think that the authenticity of subject matter becomes a shared phenomenon – not just something that I believed was worthy of turning into art, but a recognition of the fact that artist and viewer have to share something. I think that there needs to be some kind of co-creativity between the viewer and the work.

These works present us with the opportunity to dive into an accretion of meanings that are constantly in flux between context, content, and materials. Although the choice of materials used varies from piece to piece, the materials are treated as virtual co-creators of the works. Their very nature dictates the role that they play in the meaning of the pieces. Henderson acknowledges this as her intention in the piece 70 times removed from the original.

It is made known through the work’s description that there are actually 69 images in the sequential video work. The one time removed referred to in the title, but not pertaining to the number of images, refers to the remove that I think exists between a viewer looking at anything which is presented as an artwork and the artwork itself. I wanted to make reference to that initial removal. . . . The particular method of slide duplication used in making this work resulted in the edges of each slide being slightly cropped by the mount holding the slide each time a duplicate was made. This resulted in the actual image appearing to zoom in to the center of the slide, losing information at the edges. Another thing that happened using this method was that the discernible image degenerated so much as to be no longer there after only about 15 duplications. The remaining slides continued to be duplicates of duplicates, but in the absence of an image, what became more visible were the small imperfections of the duplicating process, such as fragments of dust or fibers that were caught on film and then became part of the fabric of the next slide, and so on.

As viewers, we are faced with the realization that we are free to think or do anything within this open space. At the same time, though, we are not fixed, independent travellers crossing a time-based work. Our minds continuously search for associations and relationships with personal experience and thought. 70 times removed from the original is reminiscent of the work of Michael Snow, particularly Wavelength, a 45-minute film made in the 1970s in the artist’s loft. The camera seems to be at a fixed point and completing a zoom across the studio. This continues throughout the film until the lens reaches its smallest aperture and is focused on a photo of an ocean wave taped to the studio wall. The soundtrack consists of the steadily modulating frequencies of the camera motor’s sine-shaped sound waves. People walk across the studio as the zoom is taking place, but their actions remain simple and direct. Snow proceeds to strip away certain elements of cinema in order to draw attention to a cluster of perceptions that forms as the camera starts to record. We are faced with similar considerations when entering the gallery-and-film experience of Karen Henderson’s work.

In 70 times removed from the original, the film loop has been developed from a conscious choice of materials and has a deliberately chosen duration. The work carries a sense of precision that contrasts with the imperfections in the quality of the transfer from slides to video. This disparity jolts us into reflecting upon the progression of experiences as complex, unpredictable patterns that are not always seamless.

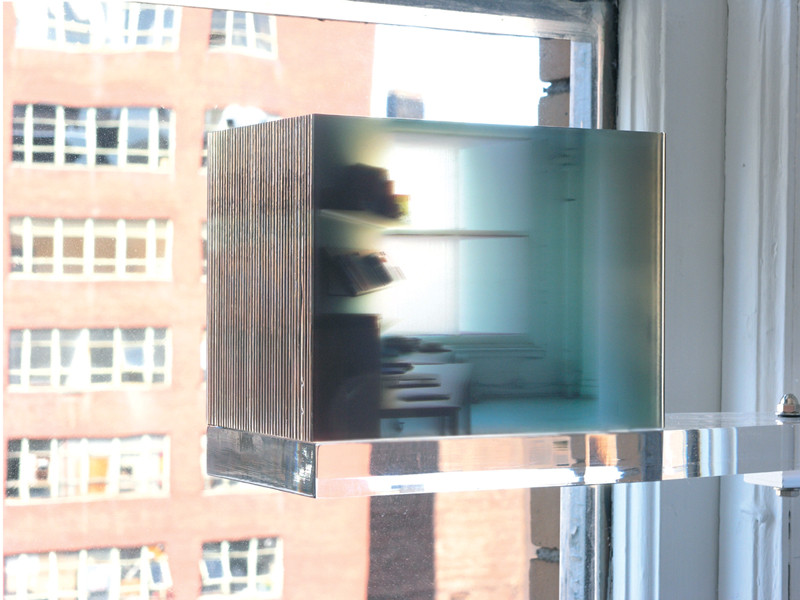

In another work presented by Henderson at Optica, we are witness to a passage of time, which has been captured and printed on pieces of glass, then assembled in front of the location where the recording took place.

In most of my recent work there has been some kind of condensing of the way that time is registered visually. I’ve worked with the film process, where the image or moment changes from one frame to the next and is seen as a time-based experience where it starts, progresses and stops. I’ve also worked with switching this film linear process into one which is sculptural like a deck of cards, where each frame or photograph is on a transparent layer and stacked so that you can see all frames all at once, such as in 40 consecutive photographs of here. In terms of the passing of time being represented in this way, this allows for looking at the moment before and after any given point, all at the same time. To make this work, forty consecutive photographs were taken of the gallery window and some of the surrounding area. The photographs were printed onto clear acrylic sheet and stacked in order to form a solid block. It was mounted on a clear acrylic shelf and installed in front of the window which appears in all of the photographs. In the photographs, the glass in the window reads as clear, which in turn allows the light from the real window to pass through the work and illuminate the interior of the block.

The work of Karen Henderson offers us an understanding of our physical space as something that is composed of synergistic elements. This idea is present both in the physical appearance of these works and in how we read them. We are faced with an illustration of experimentation and intuition and of how these abstract concepts play a role in the artwork, our imagination, and the artist’s imagination. The idea that empty spaces can offer freedom to both the artist and viewers is something that can be shared. The works add sensual dimensions to the passage of light and time, suggesting an elusive relationship between thought and emotion whose creative potential is limitless.

Natalie Olanick is a visual artist, writer and educator. She has written for Lola, B-312 and Mercer Union. In February 2005, she presented a solo show at WARC gallery in Toronto.