[Fall 2005]

April 9–May 22, 2005

Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art

The word “harrowing” readily pops to mind when viewing Donigan Cumming’s work. This word has broad, stock associations with both individual and empathic suffering: a lengthy battle with an illness, one’s experience nursing a friend through an illness, and, perhaps most oddly, an affecting, sobering movie about illness can all be described as harrowing. Cumming’s art, an aggressive, unabashed account of those who are forced to bear their mortality openly and awkwardly – namely, the ageing, the sick, and the addicted, many of whom the artist knows intimately – is a fine example of all three intents. But “harrowing” is, of course, also etymologically linked to Catholic dogma, to the idea of the harrowing of hell, when Christ, between his crucifixion and resurrection, makes an infernal descent in order to gather sinners and bring them heavenward. Cumming matches this intent as well, for he seemingly wants to offer redemption to his subjects as well as himself, not necessarily through spiritual or emotional valorization, but through the apparatus itself, which acts as a platform, a stage, on which some kind of glory can be bestowed via a combination of ridiculous histrionics and genuine contrition.

During the tenure of Cumming’s Moving Pictures show at Toronto’s Museum of Contemporary Canadian Art, many resisted this schema. Indeed, even though there is now a distinct niche in the photographic canon for the depiction of the abject (Diane Arbus, Shelby Lee Adams, and Richard Billingham come to mind), our vulnerability in the face of it seems somehow perennial: Can we still bear to look at these aberrations? Can we muster up the same courage as the photographer, who had the gall to look first? We feel dared, morally besieged: the work is exploitative, voyeuristic, manipulative, misanthropic.

The curator of Moving Pictures, Peggy Gale, anticipates this heated response in her essay accompanying the show: “We may feel guilty watching here, a little unclean at the contact, virtual though it may be. At the same time we are fascinated to know more, to see more thoroughly, and our curiosity can offend no one: these images already exist.” Gale’s last assertion has some risky implications (how can the act of looking possibly absolve us from any and all complicity?), but her emphasis on scrutiny is crucial. Cumming’s work is not reportage; he is neither a journalist nor, for that matter, a diarist. He is an artist invested in construction. There are, accordingly, strong narrative conceits (sometimes mythic, sometimes hackneyed or absurd) at play, which in part are meant to challenge the way we look at suffering as either fundamentally ennobling or pitiable (Cumming is no Sebastio Selgado). The commitment to fiction in Moving Pictures is, in fact, relentless: Cumming puts his subjects where we don’t expect them to be; he blames them, unjustifiably lionizes them, and even appropriates their misery. Duplicity, in this case, becomes the surest, and sometimes the only, way to truth.

We are welcomed to the exhibit with Lying Quiet (2005), an assemblage of 119 inkjet prints that introduces Cumming’s vast collection of characters, many of whom are visible only through body parts or non-physical detritus. The scale of the work requires peering, and returns flatly repugnant glimpses of suffering and decay: faces with eyes either violently closed or open, split crotches, raw orifices, a grotesquely infected and overgrown toenail. Cumming’s view of human rot here is unflinching, near-microscopic, and dumbfounding (one image is of a barely literate note that reads “DON CAL HE SAY TO CAL HIM BACK”; language is hardly current in the shadow of these fantastic specimens).

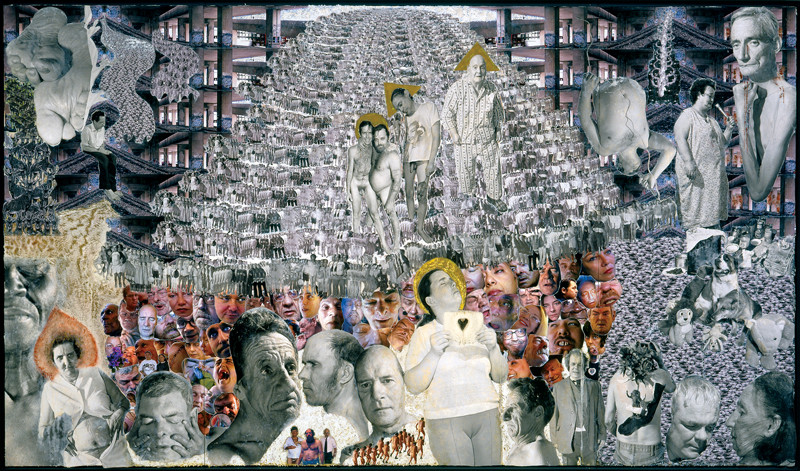

An ensuing, larger piece entitled Prologue/Epilogue (2005), effectively a diptych composed of photographs and encaustic on two substantial wood panels, starts Cumming’s diligent, conflicted myth making. As in Lying Quiet, the subjects appear in a collage: here, Dante and perhaps The Ghent Altarpiece are the grand, art-historical reference points. Prologue is the Inferno, then, the encaustic forming stalactite-looking shapes over a vista of parched earth, where a sea of cut-out heads are surrounded by limbs. In Epilogue, there is a concerted reconstitution; figures become sanctified with Byzantine-style halos, and are in colour (Prologue only shows them in black and white). The piece’s enduring image is what looks to be a procession of lost souls awaiting entry into a glorious afterlife.

Other, much less valedictory video and photographic works are more attentive to the construction – and potential hollowness – of the pathos going on here: a quartet of inkjet vinyl prints, for instance, nude, black-and-white shots of Cumming’s long-time model Gerald Harvey, show an unsightly piece of flesh (it’s hairy and meaty – not unlike John Coplans’s, actually). Again, an instinctive reaction arises: one wants to wince or gasp, perhaps to emote (Harvey could be ashamed, downtrodden, and he is lit in a saintly way, from the side). But there is also a ludicrousness present: Harvey is clearly posed, and seems both aware of and uncomfortable with this. It’s as if Cumming has tried to pass a devil for an angel, but forgot to cover his horns.

Indeed, Cumming’s concocted passion play is, ultimately, as much for himself as for his motley subjects. Often, especially in his video work, such artful treatments are indifferently welcomed; in A Prayer for Nettie (1995), for example, which importantly marks Cumming’s turn from photography to video, he dreams up an over-the-top, achronological eulogy for Nettie Harris, another long-time model (if Cumming were Warhol, Nettie would be his Edie Sedgwick). Harris, elderly throughout her collaboration with Cumming, appears as unafraid of death as of her shrivelled nakedness. She does not need this piece; Cumming does. He may be vicariously mourning his mother in Prayer (just as he may be vicariously mourning his brother through the Harvey photos); in feeding confused participants melodramatic lines to say about Nettie, he comes off as a neurotic, recalcitrant Hollywood director, trying to steer a hapless cast and crew.

Moving Stills part I (1999) and part II (2001), a three-channel video installation, is the pith of this artist/subject junction. Cumming himself stars in one of the pieces as a delusional paranoiac, amusingly taking on an assortment of Tennessee Williams-type characters, lips glistening with sweat. He seems no different than his other, “real” subjects: Colleen Faber, for instance, whose tears are rendered in cinematic slow motion, or Pierre Lamarche, whose wringing confession is given a cheesy violin flourish. Manipulation is everywhere, Cumming asserts, even – or, rather, especially – in the gutter and the soul. And that’s where it’s needed the most.

David Balzer writes for eye Weekly in Toronto and has contributed to Canadian Art, Cinema Scope, and Maisonneuve. Vidéographe has just released a DVD collection titled Donigan Cumming: Controlled Disturbance, featuring 18 titles spanning over 10 years of work, excerpts from a workshop given by the artist, 8 essays on Cumming’s work, and 2 bilingual booklets.