[Fall 2005]

Venice, Italy

June 12 – November 6, 2005

The cutting edge of today’s art ought to be the stuff of tomorrow, or so the contemporary belief goes. A visit to the fifty-first edition of the Venice Biennale highlights the importance and complexity of the relationship between the two elements of this belief: time and art. This year’s biennale presents a remarkable number of photographic and video-based works that are linked – through either subject matter or medium – to the concept of time.

Moving Photography

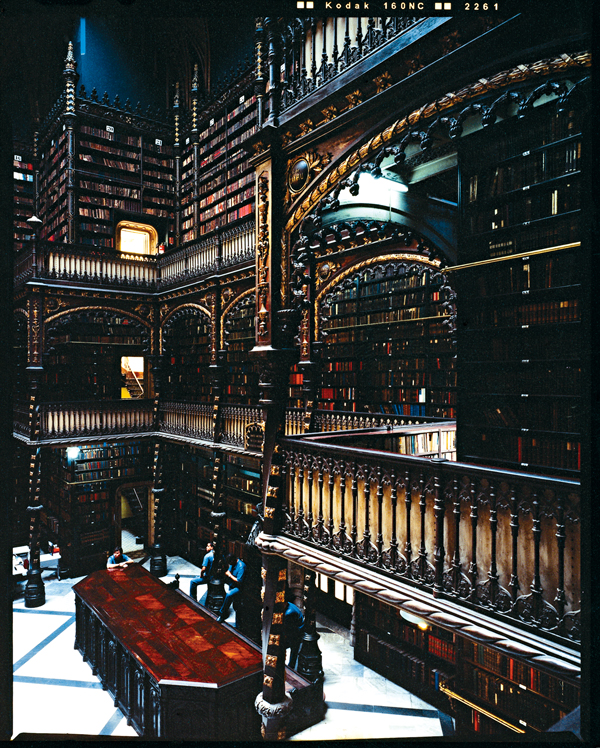

One of the two artists selected to represent Brazil, Caio Reisewitz, occupied the first of the pavilion’s two rooms with six large-format colour architectural photographs. Three images on the left-hand side of the room show Brazilian colonial interiors: a heavily gilded Baroque church, a richly sculpted library, and Caravaggio-esque details of books. The three images are incredibly rich in detail, offering viewers a panorama of textures. The three images on the other side of the room show extremely modern interiors: large, empty spaces, in which textures are obliterated to make way for pristine plays of volumes and geometric forms. It seems as though the overall interiors have been transformed into colossal abstract sculptures. The juxtaposition of the works raises the question of whether these completely different interiors exist simultaneously in the same city. A strong sense of time is present in this juxtaposition – not a before-and-after sense, but a sense of simultaneous time, sped up and doubled, so that nineteenth-century exuberance and modern minimalism coexist in the present. Such coexistence of past and present suggests a rapid acceleration of time. Yet these are still images, photographs. Instead of acceleration, there emerges a slowing down that is strangely echoed in the vast empty spaces depicted in the photographs. Past and present coexist, leaving no room for the future.

Greece, represented by George Hadjimichalis, offers a pavilion-wide installation called Hospital. Within this installation, two rooms on either side of the entrance form a piece called The View from the Windows (2005). It contains nine slide projectors that intermittently show black-and-white photographs of cityscapes. Each slide projector continuously shows the same view, arranged like windowpanes along the wall. The most interesting aspect of this work is the sense of time attained through the succession of projected images. The set-up strongly suggests a sense of evolution, yet each projector stubbornly shows a single image. Viewing the work, one finds oneself waiting to see what the next projected image will be, but it is the same one, over and over. The stillness of the image is stretched over moving time: photography occupying the no-man’s-land between video and still images.

Video is still a very new medium compared to painting or sculpture, or even photography; yet it is evolving at a very fast pace. Every year, a new form of video art, a new twist on the versatile medium, emerges. Many video artists have now moved on to video installations, in which the environment of the projection is altered so as to contribute to the artwork. Multiple simultaneous video projections, multiple screens, fully integrated installations, and similar devices are used to create “full art experiences.”

Such a “full art experience” is presented in the Montenegro–Serbia pavilion. There, Natalija Vujosevic is exhibiting a video installation called In Case I Never Meet You Again (2005). This piece is composed of two video presentations on television screens flanking a large video projection. On the two televisions, the videos are identical, presenting a rapid succession of still images. As with Hadjimichalis’s piece, the individual stills suggest personal memories – snapshots removed from a family album and presented in a rapid-fire fashion. The large projection, on the other hand, shows what, at first glance, seems to be a still image: two heads in profile, a man and a woman staring in each other’s eyes. But then you notice that they sometimes tweak their mouths a little bit, bat their eyelids, and move their heads slightly. The overall result is a video installation that is destabilizing because of this juxtaposition of the rapidly moving and flickering images on the two lateral screens against the peaceful slowness of the large projection. Time is distorted in such a way that the still images move faster then the central video. The natural time of the media employed has been altered, and the overall piece, content and form, speaks through this alteration.

Time alteration of content and form is also at the root of an interesting work by Stan Douglas (Canada) presented in the thematic exhibition The Experience of Art, mounted by biennale curator Maria del Coral in the former Italian pavilion. The work, Inconsolable Memories (2005), is a film projected in a darkened room. Briefly, it recounts segments in the life of a young Cuban in Havana whose existence is transformed, if not threatened, by the departure of all of his friends for the United States. However, the time line of this looped film is distorted by the fact that its alternating scenes are projected through two 16 mm video projectors. Due to the unequal number of scenes on the two loops, the projection sequence of the scenes is altered after the first run-through. The end result is a film that, even if watched two, three, or four times in a row, will never have the same storyline. The alteration and repetition of time in the movie affects the present time of the viewer, turning this work into a never-ending piece.

Officially representing Canada, Rebecca Belmore presents a performance-based video installation that was shot at Iona Beach, British Columbia, in 2005. In this work, called Fountain, she performs the act of fighting – against drowning or out of frustration, it is unclear – the ocean in which she is immersed. But water is resilient. It will not retreat; it simply splashes momentarily and resumes its previous pressure on her body. After a moment’s rest, she gets up and performs the futile task of hauling endless buckets of water to the shore. On that shore there is a burning fire. The four natural elements are present, and she is depicted as a living link between them: fighting and hauling the water, breathing the air, walking on the soil, and igniting the fire. At the end of the one-minute loop, she walks to the camera and throws a bucket full of water at it. But as the water emerges from the bucket it is transformed into blood. It hits the camera, covers the lens, and slowly drips down. So doing, it turns everything in the scene to crimson and effectively links the viewers with the elements, and with Belmore herself, through blood. This video is projected onto a wall of falling water.

Perhaps due to the speed of the falling water, or the extra barrier between the images and the viewers, the video seems oddly slowed down and slightly deformed. The sensation is similar to underwater sounds and movement: slower and softened as though wrapped in cotton balls, yet imbued with a sense of strength. The multitude of layers present in both the content and the form of this video installation encourages a questioning of the edges of this full art experience; one wonders if one is outside the water looking in, or inside looking out.

The video installation by Kyrgyzstani artists Gulnara Kasmalieva and Muratbek Djoumaliev, presented in the Central Asian pavilion, also encourages viewers to question their own position. When one enters the dimly lit smallish back room of Trans-Siberian Amazons (2004), the first things one notices are the dozens of plastic travelling-salesmen bags. These chequered plastic bags, which seem to be immensely popular in African and Asian markets, cover the four walls from floor to ceiling. In the middle of three of the walls, at eye level, the artists have planted three televisions, each featuring a three-minute looped video. On the two screens facing each other, the videos are of train tracks. Advancing on one screen, and receding on the other, these videos give the impression that the installation is the actual train, moving steadily forward on a never-ending journey through the rough landscape of Kyrgyzstan. This steady forward motion is oddly reminiscent of Stan Denniston’s work From as far away as hope (see “Stan Denniston: Stills,” Ciel Variable, June 2005).

On the third video screen, there is an old woman sitting in a cramped train compartment, singing softly. Her husky voice, the rattling sound of the moving train, and the crowded train compartment – combined with the crowded overall installation – create an all-encompassing world. As a viewer, you are on the train with the old travelling saleswoman. You can almost smell the musky leather. Cut away from the outside world and immersed in this train world, time seems to slow down. Though the videos themselves were not tampered with, the unhurried rhythm of the woman’s songs and the minimal movements on the three screens are evocative of bygone eras when the pace of life was a fraction of what it is today. This variation on time is yet another aspect of the ephemeral instilled in this year’s video works at the Venice Biennale. The work’s physicality in the present introduces time gaps and misalignments that trigger reactions.

Fighting Time

These works manipulate the fourth dimension as a medium; in the process, time is transformed. Slowed down, immobilized, frozen, or sped up, it is sculpted beyond recognition. In the biennale’s The Experience of Art exhibition, the largest room is occupied by video works that focus on the materiality of time and its transformative possibilities. The works by English artist William Kentridge shown in this room are large-scale projections. In one of them, Torn Self-Portrait (2003), Kentridge has filmed himself as he rips to pieces a life size-portrait of himself. However, the video is presented backwards, so that viewers are faced with a mad artist who randomly puts together pieces of cardboard found lying around his studio. An odd magic quickly settles in, since the juxtaposed pieces mend themselves into a perfect portrait of the artist. Kentridge then imitates the drawing’s posture, and quietly walks away from the screen, freeing the stage for another loop of the video.

This work brings a new twist to this year’s reflection on the concept of time and its link with art. By inverting time, Kentridge is questioning its constructive nature. The work is created in a progressive manner, beginning with nothing but scraps of paper and ending with a full work of art, yet time is flowing backwards. Can the production of tomorrow be the inverted destruction of yesterday? And what does that entail for the idea of the evolving nature of art over time?

The evolving nature of art over time is also questioned by Colombian artist Oscar Muñoz. In the Istituto Italo-Latino Americano pavilion, he presents a video work called Re/trato (2003). This title combines the notion of the trait, or trace (trato), the act of retracing (re-trato) and the portrait (ritrato). All three aspects are present in this video work, which is a twenty-eight-minute loop of a hand tracing the outlines of a man’s face. However, the drawing is made with water on a piece of absorbent paper, so that by the time the artist is almost done with his work, his first traits have already disappeared from the sheet of paper. The artist is therefore inching toward a work that will never be completed. His art evolves over time just as it simultaneously dissolves. However, Re/trato is not the never-completed drawing, but the video of its production process. Time might be an enemy of the artist attempting to complete the portrait, but it is the ally of Muñoz’s video.

Muñoz’s work, as well as all other works discussed above, shows how multi-faceted time truly is. Simultaneously ally and enemy, fast and slow, single and plural, ephemeral and eternal, time is fully explored in the multitude of photographic and video-based works exhibited at the fifty-first Venice Biennale. With its limitless versatility, video installation is proving to be the contemporary medium of choice through which to approach this timely topic, be it projected on paper, screens, walls, or even water.

Jean-François Bélisle is an independent art critic currently completing a master’s degree in art history at Concordia University, Montreal.