[Spring 2006]

by Alice Ming Wai Jim

During the past three years, I accumulated images on different attempts, but all the attempts had similar results, I treated them all as my self-portrait. . . . No matter what the camera focuses on, people or still life, the consciousness of self-cognition hence is hidden in my art practice. The image presents a part of the objects themselves and a part of my mirror-self, from which I discover my existence.

⎯ Chih-Chien Wang

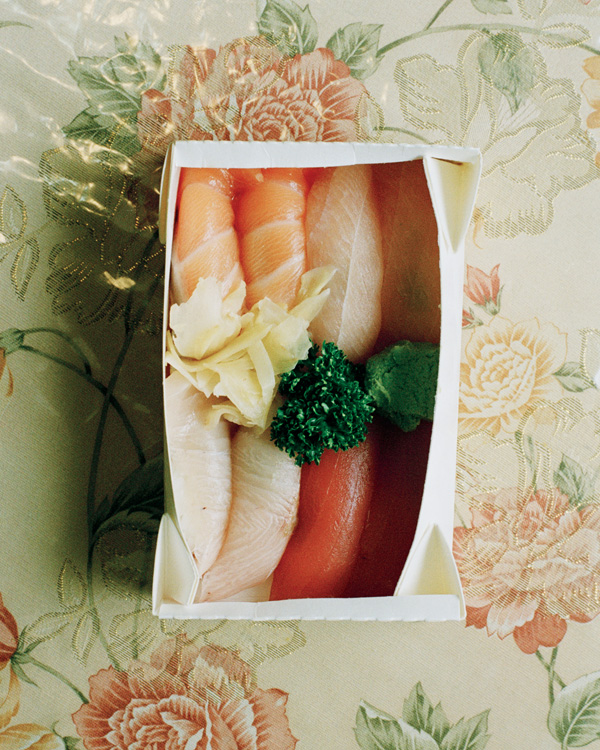

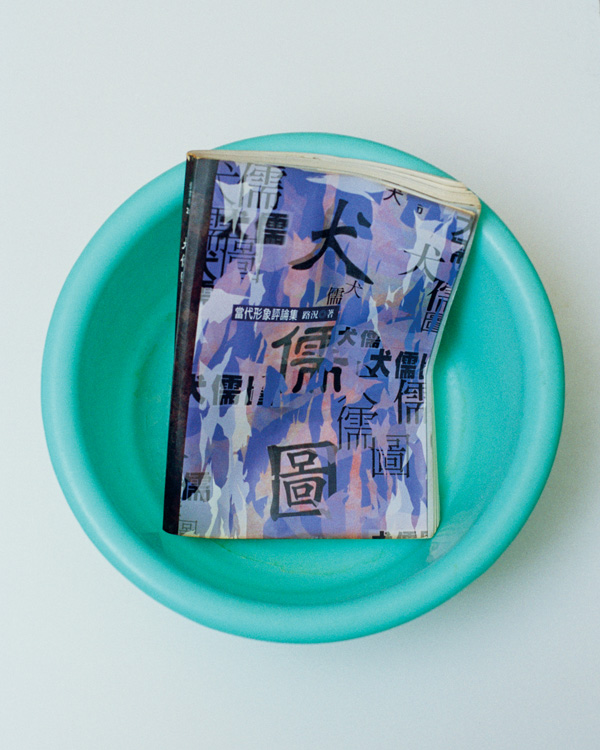

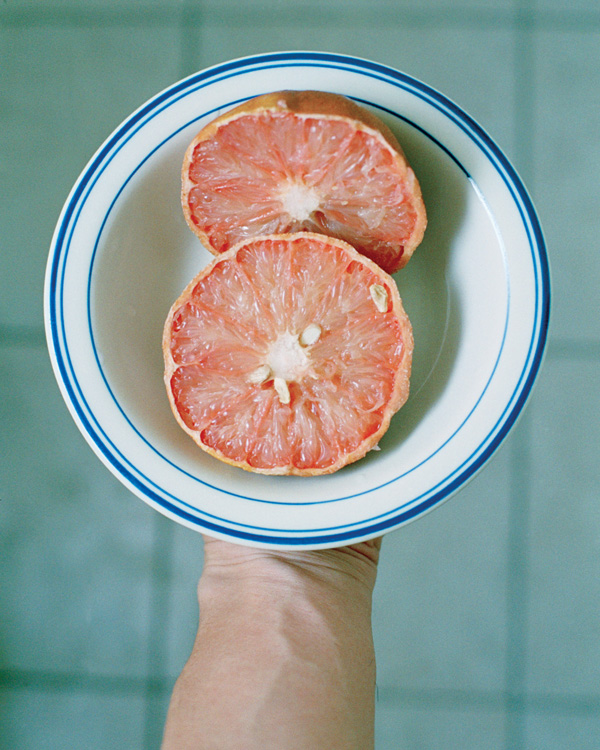

There is definitely something uncanny about Chih-Chien Wang’s pictures, both still and moving. Wang photographs objects, people, animals, and other subject matter drawn, for the most part, from his domestic universe, ranging from ordinary household items and the next-door neighbour to dead birds and a majestic white steed. Particularly abundant in his photographic archive of the everyday is recurring imagery of arbitrary instances of plant life and foodstuffs in various stages of freshness or decay. In the series of forty-eight photographs for his recent solo exhibition titled The Centre of the Forest is a Lake Like Mirror, an open sushi lunch box and a plate of gourmet-size crabs are presented only several pictures away from images of a plastic bag weighted down by a pound of previously frozen squid, a torso with a bowl of presumably preserved fish, several rotting or wilted legumes, and an offering of two halves of a grapefruit left out to air too long, among other gastronomic experiments.

This full spread, on all four walls of the gallery, is punctuated intermittently by such evocative images as a head wrapped in newspaper, a pair of legs – a woman’s – holding dried branches by the toes, leftover takeout, food containers, other (by definition) disposable packaging, and a number of portraits – including an eerie self-portrait of the artist in a hooded jacket with one eye open and the other shut, an older woman who appears four times, each time in a different outfit, and a young girl, a friend’s daughter, in a pink jacket holding a dead bird. Meanwhile, allocated according to their utilitarian purpose, the household items and supplies divide the familiar turf of Wang’s Spartan living quarters into the customary areas of kitchen (victuals, dishes), bedroom (sheets), vestibule (jackets), and bathroom (toilet paper, unused). With such a panoramic assemblage of different subjects, not quite objects of ethnography, poised to enter into curious relationships with each other, and ready-made to be transmigrated into the realm of the unfamiliar, it is not surprising that the term “uncanny” emerges.

These banal yet disquieting images – their format is similar: mostly dead centre of the photograph and against a muted background – unwaveringly bring forward the human body’s uncanny relationship with hunger, with food: the very sustenance, a foreign other that it is repeatedly required to incorporate and eliminate in order to exist. In Smile Yushan, a new video work accompanying the exhibition, this relationship – between body and consumption – and, importantly, the image technology used to capture it are exposed at virtually the same time, when both the viewer and the filmed subject become conscious of the connection. Made from old footage filmed in Taiwan, the thirty-second loop records, almost by chance, Wang’s partner Yushan Tsai (a documentary filmmaker) asking about possibly having dinner after a long day of shooting. She is noticeably concerned since they had already missed lunch, only to change her countenance almost immediately upon realizing that the tape is still running. She promptly reminds the person behind the camera, the artist, that the moment should also be captured by a snapshot.

Perhaps it is Wang’s still lifes that gesture more toward the memento mori, even the vanitas (tufts of hair, dried flowers, and decomposing victuals). These are made all the more threatening by how they suggest a changed sense of time, their various states of rise and decline held in stasis by containers shaped like Petri dishes or freeze-framed between glass slides as if they were specimens of the latest onslaught of biotechnological attempts to prolong life. The logic here, however, is not so much according to serious scientific classification (there is no narrative per se) as it is simply to afford a new shelf life. And of course for contemporary audiences, given today’s advanced means of inducing panic wars, the chances that Wang’s rather banal images could trigger any major anxiety attacks over the brevity of human existence are less than those that his picture collection may serve as an aide-mémoire for past events and human activity – “not thoughts but images, memories.”1

More to the point, understanding the focus of Wang’s project solely through the presence of uncanny motifs in fact denies the transformative ability of this particular collection to bring forward other concerns. Ultimately, for Wang, what began as a project to document the artist’s self-portrait on a daily basis has culminated in an image world of repeated motifs, intimate and alien at the same time, that not only relate to the symbolic currency of food and household consumption practices but also affect memory, spatialize human relationships, and reflect social and economic status. Wang’s art thus is not about displacement as much as it is about points of existence. Accounting for both the physical and social habitat, he relates work and production to home and food culture. A closer look reveals how his unsettling yet whimsical trash aesthetic is less the outcome of a random, erratic collecting impulse than of a process of selection that has taken on specific meaning for today’s commodity culture. With the emergence of consumer society, themes of debris moved to the forefront of attention, and the interest since the 1960s in spoilt foodstuffs and garbage as raw materials for works of art remains as concentrated as before.

In The Centre of the Forest is a Lake Like Mirror, viewers can be drawn into a general reflection on how our lives are increasingly measured in terms of the shelf life of the disposable commodity. The most striking characteristics of mass culture (today’s news, tomorrow’s fish-and-chip wrap) and objects of mass production (plastic grocery bags lining trashcans) – from household necessity to cast-off – are their emphatic tangibility and immediate physicality, indisputably linked with issues of excess and elimination, or, to use an industry euphemism, “waste disposal.” This brings us to the related issues of storage and recycling, which are so inextricably bound up with the accumulation and consumption of goods that, in their substantiality and knowability, they virtually preclude any uncanny effects possibly attained heretofore.

Wang’s other video produced for the exhibition, City, Move, Souvenir, in fact can be seen as a culmination of his concerns: it considers the global economics of contemporary waste societies, while at the same time it integrates, according to the artist’s statement, themes of “decay of cognition, identity, migration and language practice” that he has been interested in since he moved to Montreal in 2002. Initially filmed in Keelung, a port city on the east coast of Taiwan, the video work follows several members of a Buddhist organization called the Tzu-Chi Foundation as they tirelessly forage through the city for scraps of cans, metal, bottles, clothing, and paper – anything that can be recycled for money to raise funds. Unlike conventional documentary-style films, however, this narrative is frequently interrupted by cuts of footage taken in Wang’s French class in Montreal of his classmates making oral presentations. The work reflects, on one hand, the required translation of goods and services and, on the other, the material effects, oscillating between abundance and lack, of what Susan Strasser has called a “throwaway culture,” in which economies deliberately demand the production of ample materials for purchase and distribution that simultaneously end up filling scores of landfills worldwide.2

According to Ingrid Schaffner, “The process of storing is always one of mirroring and self-evaluation.”3 In a sense, Wang’s pictures are not merely storehouses for a past worth remembering; they are also placeholders of the present – perhaps to record his own migration story, which so urgently compels him to accumulate image upon image to create a place of belonging; perhaps to actualize a kind of anamnestic possibility by rescuing devalued objects from consignment to the trash heap. But more than anything else, it is the four images of the white horse, which, despite its materiality, remains largely imaginary, that ironically return us to the self-reflexive nature of Wang’s project. The horse, the only subject in the photographs taken outside of the artist’s residence, emblematizes a mental state of projection in which the boundaries of the artist’s quotidian life and the world of fantasy begin to wobble. Describing his emotions about his Dazibao exhibition, Wang talked about how the feeling of being surrounded by images was “like sitting in a forest surrounded by trees and smelling or hearing them,” and how an image was formed in his mind “in which there was a lake reflecting sunlight in a hidden corner deep in a forest, like in a fairy tale or a fantasy world” – hence the title – and was “part of the reason the white horse came into the project.”4 Without a doubt, it is the beautiful white horse that transports the viewer from the banality of Wang’s homely domain to the magical world of fantasy – a fantasy, according to the artist, “made out of fragments of a solitary life” in an unfamiliar urban culture to which he is accustoming himself and that he is incorporating into his practice. Inexorably, Wang’s self-reflexive almanac is an unfinished and unfinishable project: let’s hope that these self-portraits reflect what we will see in the future.

2. Susan Strasser, Waste and Want: A Social History of Trash (London: Metropolitan Books, 1999).

3. Ingrid Schaffner, “Deep Storage,” in Deep Storage: Collecting, Storing and Archiving in Art (Munich: Prestel, 1998), p. 21.

4. E-mail correspondence with the artist, January 22–24, 2006.

Chih-Chien Wang, born in Taiwan, moved in 2002 to Montreal, where he now lives and works. He obtained his BFA in film and theatre from the Department of Drama at the Chinese Culture University in Taipei, in 1994, and worked as a cinematographer for daily news shows and as a documentary director for TV companies in Taiwan. He then moved to Canada, and is currently finishing an MFA in photography at Concordia University. His work was recently shown at the Musée de l’Elysée, Lausanne, Switzerland, in the exhibition ReGeneration, 50 Photographers of Tomorrow, 2005–2025. Wang has had two recent solo exhibitions of projects supported in part by PRIM and CIAM: The Centre of the Forest is a Lake Like Mirror at Dazibao (Montreal) and Home-Scenery at Art-space (Peterborough, Ontarion).

Alice Ming Wai Jim is an art historian and critic. She is currently curator of the Vancouver International Centre for Contemporary Asian Art (Centre A). Her writings on contemporary art and spatial culture have been published in various anthologies and periodicals.