[Fall 2007]

International Center of Photography, New York

September 14, 2006–January 7, 2007

The debate over the effect of technology on the land has always been central to American photography and culture. In the nineteenth century, it was about the optimistic arrival of railroad tracks in the wilderness; in the early twentieth century, it was about the growth of new, modern cities; and in the later part of the century, from the 1960s to the 1980s, it was about the appearance of industrial landscapes and the social physiognomy of suburbia. Today, this core debate is about the more alarming realities that are called Hurricane Katrina, wars in the Middle East, and global warming. How do photographers reflect on these urgent matters, and how does an institution such as the International Center of Photography in New York respond to the current works and issues?

Ecotopia, the second triennial of photography and video at icp, is an ambitious survey of works by thirty-seven artists from fourteen countries dealing with the dire condition of our planet. Al Gore’s book An Inconvenient Truth sits beside the triennial’s catalogue in the icp bookstore, almost like an appendix to the exhibition. This international venue, unique in the United States, aims to “offer a critical assessment of new or previously unseen developments in photography and video, with an eye to identifying pertinent trends or themes.”1 Three years ago, the triennial’s inquiry was about the culture of fear and estrangement post–9/11; this year, the subjects are war and ecological catastrophes – with blatant references to the current Bush administration and its foreign policy failures.

The wall texts, the installation, and the large scale of the photo-graphs and projected videos suggest a major, in-depth treatment of these alarming situations. But when we approach the works, many of them blur and mitigate our shared anxieties. icp, an institution engaged in political debate from its foundation, presents an art show in which fiction prevails over reality. Ecotopia invites its audience to read between the lines, look for tricks, and, most important, distrust the documentary power of photography and video.

Almost like a prologue, the first photographs in the show are Robert Adams’s black-and-white prints from his recent portfolio Turning Back: A Photographic Journey, documenting the industrial exploitation of forests in Oregon. This body of work is new but looks dated, reflecting Adams’s ongoing exploration of ordinary landscapes in the United States, in which the camera is focused on the marginal and the discarded. Similarly, Mitch Epstein’s visual investigation of consumption of natural resources in the United States retraces his past concerns about “American Power,” in which representations of the American pastoral are layered with power plants and ecological threats. Epstein’s masterful treatment of surreal juxtapositions in the contemporary landscape brings him to capture the effects of Hurricane Katrina in Biloxi, Mississippi, where the interior of a house has been swept away and is held by the branches of a monumental tree, kissed by the soft light of a Southern sunset. Aerial views by David Maisel of military storage facilities in the American West bear a strong resemblance to Emmet Gowin’s photographs of ecological disasters (Maisel is, in fact, a student of Gowin’s), in which horror and beauty conduct a dialogue as they are watched from the sky. These works form an exceptional group in the show, in which photography is still treated as some kind of proof, and the documentary survey of places in danger is filtered through a sense of beauty and harmony. Obviously, this is not the trend today, and the curators’ inclusion of these works appears to be a tribute to the American tradition of landscape photography of the 1970s and 1980s, when the use of large-format and colour film and the careful composition of natural environments were the goals.

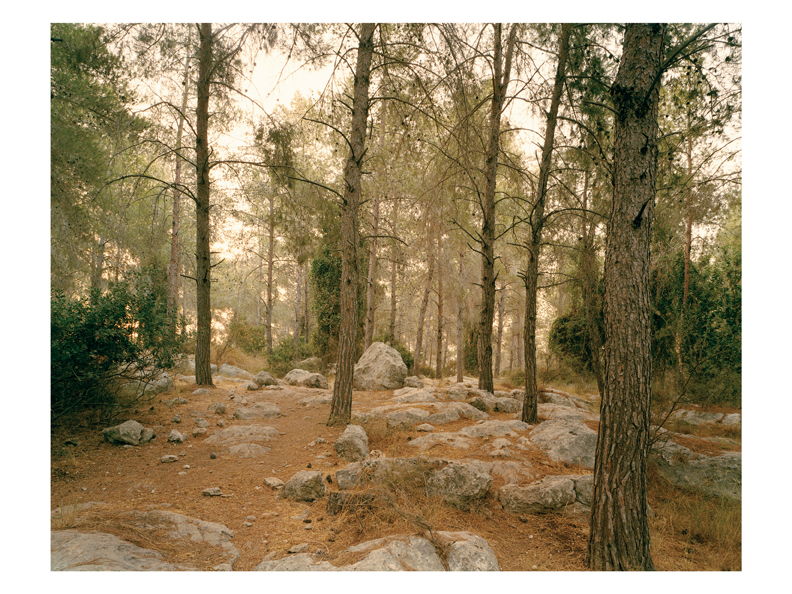

In line with Craig Owens’s analysis of the “allegorical impulse” in contemporary art, Ecotopia “does not restore an original meaning that may have been lost or obscured. . . . Rather, it adds another meaning to the image.”2 This visual transformation occurs in many works, and it is only through descriptive labels or taking a physical distance from the works that the message of these works becomes clear. This is the case for Adam Broomberg and Oliver Chanarin’s elegant colour images of deserted forests photographed through the mist of dawn. These peaceful environments obscure the original nature of this territory, where Palestinian villages have been progressively erased since 1948, and forests have been planted to cover the horrors of war. The Jewish National Fund supports the growth of this new Garden of Eden, representative of an illusory peace. As this body of work suggests, reality is not what we see in the pictures but what we filter through historical texts and conceptual explanations that are separate from the photographs.

A range of digitally made works confirms these ideas. Thomas Ruff appropriates images from the Internet and blows them up, with a resulting large-size picture that is composed of pixels and abstract patterns. From a distance, it is possible to recognize the threatening shapes of oil fumes in Iraq that look like a terrifying explosion, while up close the digital surface shows an abstract combination of soft grey tones and pastel colours that are not particularly scary. Even more radical are Joan Fontcuberta’s digital re-creations of uncontaminated and sublime landscapes, drawn from iconic images by photographers such as Stieglitz and Bill Brandt, and proving that digital imagery does not require a referent to exist. Similarly, Mary Mattingly digitally stitches together composite photographs of artificial landscapes and props; she dresses up models in khaki uniforms that she calls “wearable homes,” compiling a futuristic collection of clothing and architecture that is increasingly separate from actual human bodies.

These visual treatments of the contemporary culture of appearance become very critical when the subject at stake is war and violence. This is the realm of anti-reportage, in which photographers work with large-format cameras and contemplate the residues of the aftermath. Simon Norfolk and Sophie Riestelhueber represent the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq with romantic ruins and abstractions. Their eerie and distant views are graphic compositions in which the war is filtered through symbols and historical references. Norfolk speaks of Poussin and Lorrain to explain his “Gates of Baghdad”; Riestelhueber imagines military sentinels in the shapes of broken palm trees and translates the military wounds into a bloodless landscape of the aftermath 3 Even more radically, An-my Le treats war as performance in her two-channel video about U.S. military training in the California desert, in which soldiers’ gunshots create fuzzy atmospheres that recall nineteenth-century photographs by Gustave Le Gray documenting the imperialistic orchestration of war in the military camp of Chalons-sur-Marne. I cannot think of anything more distant from the actual Iraqi bloodshed than this representation of American soldiers acting like puppets in a disengaged rehearsal. Baudrillard’s thoughts that the Gulf War never happened came to mind as I followed these distant figures running in the desert, shooting their guns, performing unnecessary battles. Along the same lines, Montreal-based artists Carlos and Jason Sanchez stage the rescue of a dead body, transforming this image of violence into a pantomime.

If war and natural pollution are, quite logically, part of this survey about our ecosystem, another thread in the show is that of animal life – the exploitation and extinction of animals and their estrangement from the world of humans. Harri Kallio creates facsimile dodo props and reproduces them digitally in front of the backdrops of Mauritius islands. Catherine Chalmers observes cockroaches living in tanks in her Soho studio, filming them in such a way that they assume a life of their own – something between biological specimens and science-fiction monsters. Sam Easterson places video cameras on the bodies and heads of the animals, showing how this “other half” lives and moves. Alessandra Sanguinetti captures the farm life of her family home in Argentina, creating square-format colour photographs that are both nostalgic and scary. Diana Thater films three tigers playing in the swimming pool of a California rescue compound, surveying their games from above, and suggesting the physical distance from and control over these sad creatures, extinct in the wild. Mark Dion and Victor Schraeger photograph birds and wild animals along taxonomies that aim to classify and embalm these lives. All in all, these treatments of the animal world seem to suggest our separation from that side of nature, without any particular promise of redemption, but, rather, with some bitter irony.

Suggestions about global economy are raised in the work of Chinese montageur Wang Qingsong, who shows the shift to the “new China,” from the staging of a socialist protest to that of a corporate march characterized by slogans about McDonald’s and Coca-Cola. Doug Aitken constructs the new city of global communication with FedEx boxes and PhotoShop alterations, presenting this cardboard architecture in a gigantic transparency framed in a light-box.

The size and monumentality of these works (in which presentation often prevails over image quality) are contrasted with a few works in the show that are straightforward illustrations of events such as Katrina and the tsunami and are presented in the more modest format of a PowerPoint presentation. This is clearly another level of work in which the medium (anonymous cell-phone pictures, documentary snapshots, and activist photojournalism) is as interesting as the message in its capacity to report current facts. No longer pictures on the wall, these visual records question more directly the role of photography vis-à-vis politics and society, adding a layer to the exhibition that seems to contradict the overall quest of Ecotopia. The show is not focused on the kind of photojournalism that appears on the pages of The New York Times, and the inclusion of Vincent Laforet’s colour photographs of Katrina remains marginal and out of the context of its production.

Despite its seemingly engaged nature, Ecotopia addresses the heated debate on photography and the environment with allegories and abstractions, in which human beings are almost invisible, animals are enigmatic presences, and the world as fiction is about to triumph in all its complexities and squalors. The show is entertaining and diverse in its international breadth, presenting the current state of photography and video, but sadly revealing the disengaged substance of these works. As one leaves the gallery space, the world appears as a manipulated image that has no substance, depth, or presumed reality.

Maria Antonella Pelizzariis an associate professor in the Department of Art at Hunter College (New York). She participated in the Canadian Centre for Architecture’s book and exhibition Traces of India.

2 Craig Owens, “The Allegorical Impulse: Toward a Theory of Postmodernism,” in Beyond Recognition: Representation, Power, and Culture (Berkeley: University of California Press, 1992), p. 54.

3 See Charlotte Cotton, “Moments in History,“ in The Photograph as Contemporary Art (New York and London: Thames & Hudson, 2004), p. 167.