[Fall 2007]

Tate Modern, London

October 11, 2006 – January 14, 2007

Replicating the real, the Swiss duo of Fischli and Weiss play around with it all like so much spice cake. Since the 1970s, they have collaborated on numerous projects, and they have received their due recognition with this retrospective. Most often they fabricate meanings, or mythology, with an abandon born of a sense of fun. As they do not take themselves too seriously, they tend to challenge art conventions, although even challenging conventions can seem conventional these days. Their familiarity with what art is or can be seems somewhat rote, or learned, and this characteristic makes them truly Swiss. Conventional becomes contemporary art, expertly executed, as with the room full of monochrome maquettes of scenarios. The sculptures date from 1981 to 2001 and have that unfired clay monochrome look. These works are full of a sophisticated banality bordering on irony. As Weiss explains, “The intention was to accumulate various important and unimportant events in the history of mankind, and of the planet – moments in the fields of technology, fairy tales, civilization, film, sports, commerce, education, sex, biblical history, nature and entertainment.”

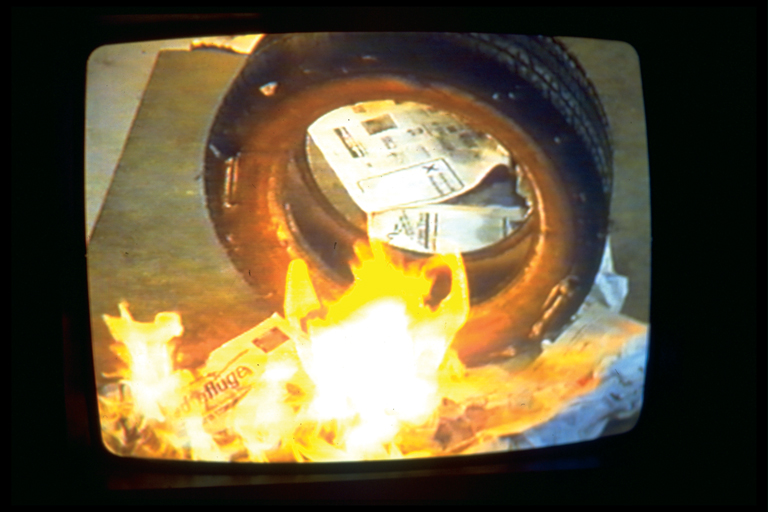

These maquettes range from Mick Jagger and Brian Jones going home satisfied after composing “Can’t Get No Satisfaction” to Herr and Frau Einstein shortly after the conception of their son, the genius Albert, to Theory and Praxis, Birth and Death, to Dr. Albert Hoffman heading home on a bike in Basel after testing the LSD that he just synthesized, to St. Anthony being tempted in a cave all alone, to a slew of popular themes. From the overtly banal to the ludicrous, the sublime to the ridiculous, these sculptures display something of the simultaneity of things that is also the feature of Fischli and Weiss’s film Der Lauf der Dinge (The Way Things Go) (1986–87), a thirty-minute sequence of visual and physical effects that play with gravity in a Rube Goldberg sort of way. Car tires, plastic bottles, candle flames, firecrackers, balloons, and liquids that light up – all these fall like dominos in a series of causes and effects. This room, more than any other at the TateMod show, was always full of viewers mesmerized by the way that the piece was set up, shot, and orchestrated. Weiss’s comment: “A professor in Germany once asked us if we were thinking about the French Revolution when we made The Way Things Go . . . because of the upheavals that lead to further upheavals.”

To capture the clichés, the duo has a room full of photos from the Airports (1987–2006) and Flowers, Mushrooms (1997–98) series. The latter photos are double exposures, and the intense colours, the magnification of what is usually detail, give them a hallucinogenic quality, and landscapes fuse into close-up plant details. A quiet, dark room consists of questions, all handwritten, projected on the walls: “Is it true that traces of aliens have been found in yogurt?,” “Should I buy a gun?,” “Is carelessness good for melancholy?,” and so on. These words meander across the wall for a few seconds, as part of a slide presentation of questions in several languages, many of which Fischli and Weiss originally posed in their little book, Will Happiness Find Me? Capturing metaphysical notions like caricatures, amid the more everyday quotations that are projected, these are themselves linear artworks, like concrete drawings or poems from the 1960s rendered into new media form. This room is conceptual art rendered multi-media with a grace and consistency born of a world in which collective memory is invisible and hidden.

There is an Enzo Cucchi–type sense of humour to the video piece The Right Way (1983), in which two characters dressed in costumes wander through an idyllic mountain wilderness worthy of Caspar David Friedrich. Costumes worn in the 1980s for the two Rat and Bear films in which the duo play about, daydream, disagree, and look for worldly success. Fischli and Weiss’s ability to painstakingly replicate the real is manifest in the room full of objects and elements from any construction site. We see pallets for carrying materials, car tires – all the elements of a utilitarian universe unfolding as it should for the developers and capitalists, right down to the milk carton, the cigarette butts (so different from Claes Oldenburg’s in conception and intent), the stray coffee cup, the discarded pizza box. It is as if art actually had surpassed economy, as the time required to execute it all were so much, and yet it occurred as an event/site/situation, and one that borders on performance art without any actors.

What makes this room so fascinating is that none of it is real. All fabricated, of polyurethane and painted to capture all the details, this is a simulacrum that is actually labour intensive and real art. Duchamp may have named objects into art, like the Bicycle Wheel readymade, but Fischli and Weiss make objects that replicate the real, rather than capture and claim the real for the realm of art, as Duchamp once did.

The saddest room of all is the first one that one enters, in which a tree trunk and its roots have been recast out of rubber, as have a cupboard and a low wall, and we see a pair of sanitation workers at work next to a manhole, with their hose descending into it. It is so heavy!

John Grande’s Art Nature Dialogues: Interviews with Environmental Artists (2004) was published in a Spanish edition by the Fundacion César Manrique in 2005. Dialogues in Diversity: Art from Marginal to Mainstream will be available in April 2007 from Pari Publishing.