[Fall 2007]

by Martha Langford

It occurred to me recently that my fascination with photographic albums may be due in part to the fact that my family never kept one: we were box-in-drawer people, my mother making good use of packaging for notepaper and Christmas cards to keep some order in our small photographic hoard.

I have this in common with who began his amazing self-portrait cycle, Familial Ground, to fill in the gaps in his photographic family tree. But there are different reasons for our respective lacks. My father’s family seems not to have bothered much with pictures. There were some on my mother’s side; I suppose we could call it a “natural disaster” that my mother’s younger sisters took it upon themselves to throw out all the pictures of people they could not identify on the spot. Such bravado is now rare. In Goldchain’s case the lack of photographic images is part of a collective history. He guesses that there were more pictures of his forebears, possibly even albums, that went missing as the family was dispersed or deported to be murdered before 1945. Left to their descendants were photographic scraps supplemented with a mix of fact and legend. When he became a father, Goldchain decided to rebuild the family album from the ground up.

If the idea sounds sentimental, the results are anything but. Something startling and original was to be expected from a photographer of Goldchain’s sensibility and experience. Born in Santiago, Chile, in 1953, Goldchain lived in Mexico and Israel before emigrating to Canada in the mid-1970s. His first major photographic project emerged in the 1980s within the “new colour” movement. Goldchain used this material to make images of place and memory: lyrical studies of light and shadow; hallucinatory figures of muted violence; split-seconds of naked confrontation. All of these photographs conformed to the rule of exile, forming a compulsive backward look, sometimes romantic, sometimes bitter. Goldchain cast a wide net into the mega-culture that had spawned him, photographing wherever he could in Latin America. In 1989, he published a monograph, Nostalgia for an Unknown Land (1989). For his non-Latino readers, the title could be taken as a wanderer’s expression of loneliness and his desire to share his memories of a remote and exotic culture. But looking back at Nostalgia for an Unknown Land through the optic of Familial Ground strips it of any documentary status. The photographer’s subjectivity is something more than social and political commentary. It can best be understood by taking this notion of an “unknown land” literally, as a land that is essentially, eternally unknowable, especially to a Latin-American-Jewish child trying to find his bearings in a diasporic culture of continuous re-creation.

Familial Ground can be read as an extended search for identity, this time embodied (literally) in those who gave him life. This is a monumental question – the work responds. Installed in a gallery, Familial Ground is both physically and technically imposing: the scale of the photographs and their high degree of professionalism are designed to impress. The portraits are (to the eye, at least) large black-and-white photographs, extending a line of photographic portraiture that goes back to the nineteenth century (the Galerie contemporaine of Nadar and Carjat) and persisted throughout the last century in studios of, and for, the “greats” (the twentieth-century Canadian touchstone is Karsh). Goldchain has inherited this photographic pedigree. Everything about these portraits is made to last, as Walter Benjamin said about the first generation of photographic portraiture (he wrote of images whose ritual, setting, and lengthy exposure abjured any notion of instantaneity). For the bourgeois spectator – myself and others who have studied these images in a gallery – the effect of their unified and polished presentation is convincingly, therefore eerily, perfect. This is family portraiture as it “should be” and can be when its members are born and live out their lives in a stable, prosperous community, served by its designated photographer. In Montreal, the example of the Notman Studio is close at hand. For almost a century, it was possible for generations of Montreal’s leading families to be cast in the Notman look, a style that changed, to be sure, but gradually, always holding the line of decorum and durability against the Kodak culture of the masses. Goldchain pays the same compliment to his forebears: their portraits are timeless, and therefore, being photographs, each in its way anachronistic. Their distortion of time rings the first alarm bell in the viewer; exaggerated – dare I say monstrous? – family resemblance rings the second.

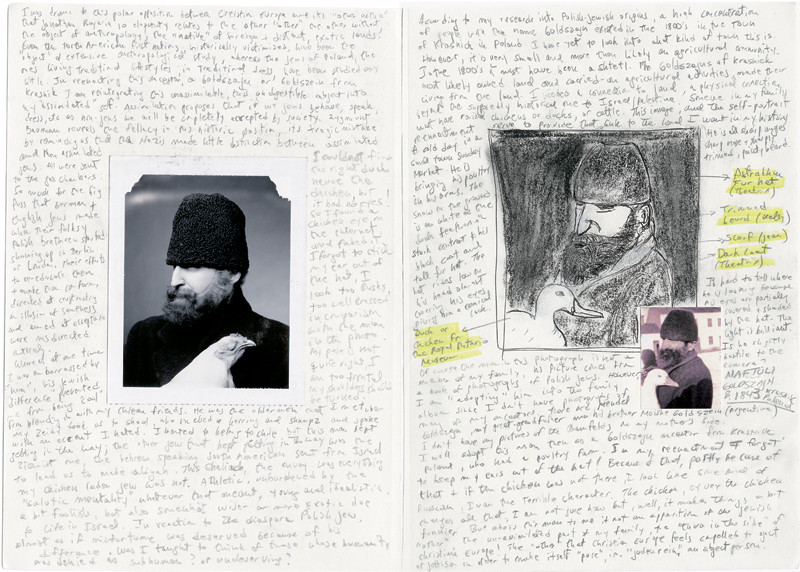

The process of making Familial Ground is a fascinating story, which the artist has carefully documented in notebooks, videotapes, and, of course, the images themselves. A few points need to be stressed. First, while each portrait is duly accorded a name and (sometimes approximate) life-dates, Goldchain has at times taken liberties with recorded history. He has, in fact, supplemented it a bit. One example is his portrait of Naftuli Goldszajn. The family cannot trace its roots through this ancestor – and it follows that there is no photograph. In this case, Goldchain borrowed a photograph of a man who might have been a relative and re-enacted it, again taking a few liberties. The man in the picture holds a live duck. Goldchain substituted a taxidermied chicken. The effect is similar, especially since the bird is held in profile (a beak is a beak is a beak). But this comparison is not taking place in the gallery. There, we are faced with a black-and-white image of a man who might have lived in Poland sometime after the 1830s. He must be a Goldchain, since he looks like all the others.

I did mention that only one person was photographed for Familial Ground: Goldchain himself. He appears in every image, his costume, make-up, props, and character carefully researched, rehearsed, and pre-visualized, with digital manipulation as the last stage. Some of the sessions were videotaped, and the results were edited and released a voice-over by the artist. Involving make-up artists and an assistant photographer, the sessions seem to have been both enjoyable and intense. Photographic values drive the process, which is all about photographic effect. Before the camera, Goldchain is his own director: his role-playing is a tour de force. With extraordinary sensitivity and real subtlety, he assumes the identities of his ancestors, young and old, male and female, real or imagined. On tape, he refers in passing to strategies for conflating identities and playing parts. As he adopts the role of his attractive and stylish grandmother, Goldchain records his desire to get the part right. That he is a man, and his subject is a woman, is of no account: the work is not about cross-dressing and gender, but about memory and history. Each of these characters is appealing, through him, for remembrance.

Should we call Familial Ground a composite self-portrait? Or to put the question another way, can we compose a portrait of Rafael Goldchain from the photographic evidence in the gallery? It seems to me that we could, simply by joining the game that people have been playing with their family photographs for almost two centuries, taking the eyebrows from this one, the sly expression from that one, possibly rejecting certain features as imports from an undesirable branch of the family or an imputed indiscretion by the mother. To this extent, we are all photographic literates and amateur criminologists – we read the face as a history of the gene pool to which it belongs. This was what I meant about the lack of sentimentality in this project. On one hand, we have “The Varieties of Goldchain Experience”: the characters share family traits, but they are also “individuals,” very much of their time, place, and personal experience – these things are written all over their faces and bodies. On the other hand, we have the strangeness of similarity, a cookie-cutter effect that some of us have seen at our own family reunions and felt roaring through our veins as inevitability and dread. The brilliance of Familial Ground is this authentic combination of pleasure and terror.

Rafael Goldchain’s photographs have been shown in Canada, Chile, the U.S., Cuba, Germany, Italy, the Czech Republic, and Mexico. His work is in private and public collections, including France’s Bibliothèque Nationale, the Canadian Museum for Contemporary Photography, New York’s Museum of Modern Art, Houston’s Museum of Fine Arts, and San Diego’s Museum of Photographic Arts. Born in Santiago, Chile, Goldchain received an MFA from York University and a BAA from Ryerson Polytechnic Institute. He currently teaches photography and digital art at the Sheridan Institute of Technology and Advanced Learning (Ontario). http://www.rafaelgoldchain.com. Oeuvre d’une vie, la série d’autoportraits intitulée Familial Ground de Rafael Goldchain s’inscrit dans une quête d’identité au sein d’une diaspora. L’artiste a créé des portraits photographiques de ses ancêtres, se basant sur des légendes familiales, de vieilles photos délavées et des images appropriées. Il s’est permis certaines libertés avec l’histoire, en incluant des figures qui auraient pu faire partie de son arbre généalogique. La série nous invite à réfléchir aux conséquences entraînées par les photos de famille et les « airs » de parenté.

Martha Langford is the author of Suspended Conversations: The Afterlife of Memory in Photographic Albums (2001) and Scissors, Paper, Stone: Expressions of Memory in Photographic Art (forthcoming 2007), both published by McGill-Queen’s University Press. As artistic director of Le Mois de la Photo à Montréal 2005, Langford included Rafael Goldchain’s Familial Ground within her thematic exploration of Image & Imagination.