[Fall 2008]

by Niki Lambros

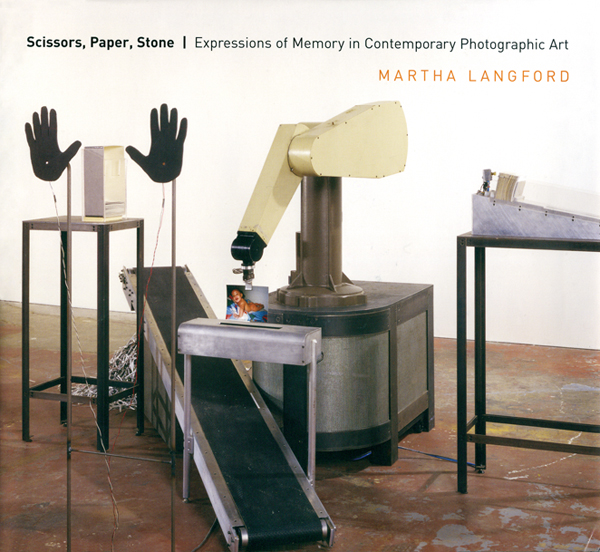

The experience of reading the latest book by Martha Langford is strangely medieval; it’s a Cappelanasian compendium, an Ars Memoriae Contemporaria Photographia. Beckett is found on a single page with philosopher Avishai Margalit and St. Augustine; Benjamin, Penelope, and Proust in the same sentence. Drawing from literature, art history and criticism, philosophy, psychology, and more, Langford presents us with a schema for a game: viewing photography, as it relates to Memory, in terms of three relational symbols whose powers to influence the quality and type of memories vie with and complete each other.

Langford “translates” contemporary photography: scissors, “the joust between remembering and forgetting”; paper, the “meeting ground between memory and history”; stone, “the relationship between memory and history.” “And this game of paper, stone, scissors, may be the Canadian way.” If anyone has the right to judge the Canadian way, it’s Langford, but while her qualified observations are certainly worth saying once, they are not easily read, however articulately, a hundred times. After all, the relationship between photography and public and private memory, between consciousness and history, has been the primary critical leitmotif in cultural analysis for as long as photography had been around.

Snapshots of a score of Canadian photographers are displayed surrounded by a plethora of analogy, quotation, and metaphor. The overall effect can be overwhelming, and the drama with which tautologies are stated, her revelations and epiphanies stacked, describes a metaphor whereby photography, as a step-child of Memory, must play out its destiny as an art-form. Still, one reads on in order to encounter more of the compelling work that Langford has been known for showcasing in her long career as a scholar and curator.

The main photographers to whom Langford refers throughout the text are represented with several exemplars. They are all fascinating, and a primary pleasure of the book. After many pages in which she describes journeys that “begin in one place, and end up in another,” she proposes the function of her analogy: “It could be argued that every work of art offers the opportunity for empathetic, improvisational interpretation, and no one would disagree. This book wants to raise those possibilities at every turn. At the same time, there are artists who, consciously or unconsciously, leave more room for spectatorial action…” (italics mine). What is done “unconsciously” by an artist is perhaps the least palatable aspect of imposing on artists constructs by which to view their work. Fortunately, Langford mostly sticks to learned anecdotes, fact-filled encapsulated descriptions, and on page 190 we are still reading explanations of the “metonymic” game.

Photography’s mnemonic forms and concepts are put under a prism; a chapter on album works talks about “collection,” “memoir,” and “travelogue.” Dialogue from the classic film My Man Godfrey frames the chapter “A Forgotten Man,” and Langford is not above mentioning tea-soaked madelines more than once.

“Remembering and forgetting” are the property of individual and collective memories; the criteria by which we choose what to keep and what to lose depends on both subject and subjectivity. What remains is History, which becomes histories of the “fugitive acts” of memory, the legacies of the past for generations who will again choose whether to remember or to consign to oblivion. She concludes with an apt pronouncement and a somewhat disingenuous question: “An art of memory is a system for encoding knowledge in signs that make it retrievable. Can that concept be translated to photography… have I done so in this book?” I believe that she has created the memory-palace in these three, albeit crowded, rooms.

It is a beautifully printed edition, the reproductions vivid and repaying close inspection, the notes, bibliography, and index thorough, if one has a tendency to name-check. Among others, we meet photographers Hamish Buchanan, Diana Thorneycroft, and Donigan Cumming in the first part, Scissors; Barbara Pelkey, Jin-me Yoon, and Michael Snow in Paper, and Carole Condé and Karl Beveridge, Robert Houle, and Robert Minden in Stone; would they approve of their assigned categories? Answer Langford’s question in the affirmative? It makes no difference to this book, which is something of a relief. As the author herself states, this book is here to raise opportunities for art, at every possible turn.

Niki Lambros is a theologian and writer of philosophical and literary criticism who recently returned to North America from twenty years abroad, mainly in Europe and Asia.