[Summer 2008]

For more than fifty years, Fred Herzog has roamed the streets of Vancouver. His camera dwells on the raw fabric of the city: second-hand stores, restaurants, storefront windows, barbershops, and vacant lots, and the people using those spaces. The selection of images presented here stems from a body of work that comprises hundreds of images. All of theses works share a bold and innovative use of colour and attest to the artist’s interest in human interactions within mutating cityscapes.

by Helga Pakasaar

“When you have seen the city to a point when you think you have done it all, the horizon will suddenly sustain a crack and a new cycle of hitherto unseen phenomena will begin to form shadows on your film.” – Fred Herzog

“Perception is to have seen.” – Fernando Pessoa

Fred Herzog began to take photographs of the urban landscape of Vancouver in 1953, shortly after emigrating from Germany, and he has not stopped since. Until 2002, he shot one hundred rolls of film a year, from which he has amassed an archive of images that contributes to the long photographic tradition of urban landscape studies. While Herzog has photographed in locations from remote hamlets in Nova Scotia to busy San Francisco streets, his focus has been on Vancouver. His in-depth study documents half a century of changes. Often revisiting the same neighbourhoods and street corners over many years, he has observed urban life through methodical investigations – what Walter Benjamin called “botanizing the asphalt.” Interestingly, while it is now entering the annals of the history of art photography, this body of work also functions as a significant record, and perhaps the only extensive documentary one, of Vancouver over a long period, offering insights into a history that otherwise could be gleaned only from commercial, government, and news images.

It could well be said that Herzog is an important pioneer in colour photography.

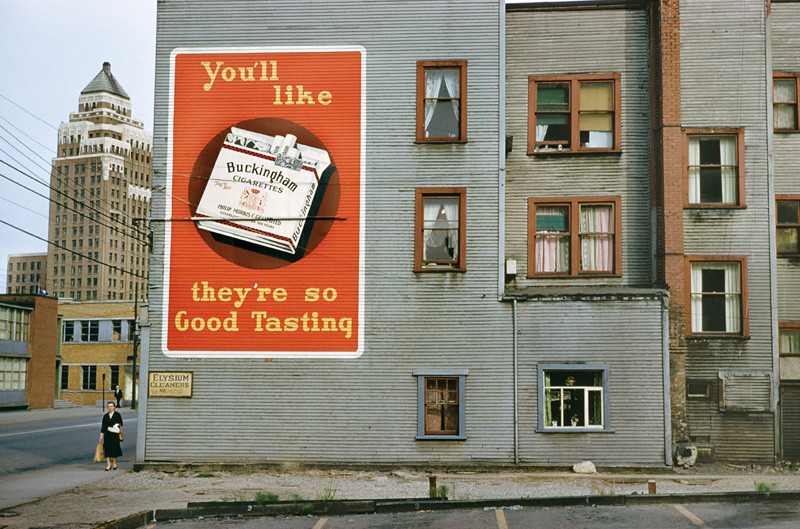

Herzog depicts an urban fabric of shifting spatial relations. Drawn to places in transition, he shoots primarily in the older working-class neighbourhoods and downtown core of the city. He has a predilection for locations that bear history and reveal the accretions of change, rather than the standardized architecture of generic suburbs and urban-development schemes. His street photographs of everyday life show a city of diverse cultural and socio-economic conditions. Waterfront scenes record Vancouver’s development from a provincial resource-based hub to a container-ship port in the global economy. Downtown sidewalks energized by the vibrant electricity of neon signs sweep the viewer through public space as an empathetic part of the crowd. The cityscape is seen as a dynamic collage of textures in which diverse handmade and commercial signs and billboards are piled one on top of the other competing for attention. Such a chatter of messages in a field of signs is no longer possible in today’s highly regulated public air space determined by strict sign bylaws and corporate control of generic billboards aimed at vehicular traffic more than pedestrians.

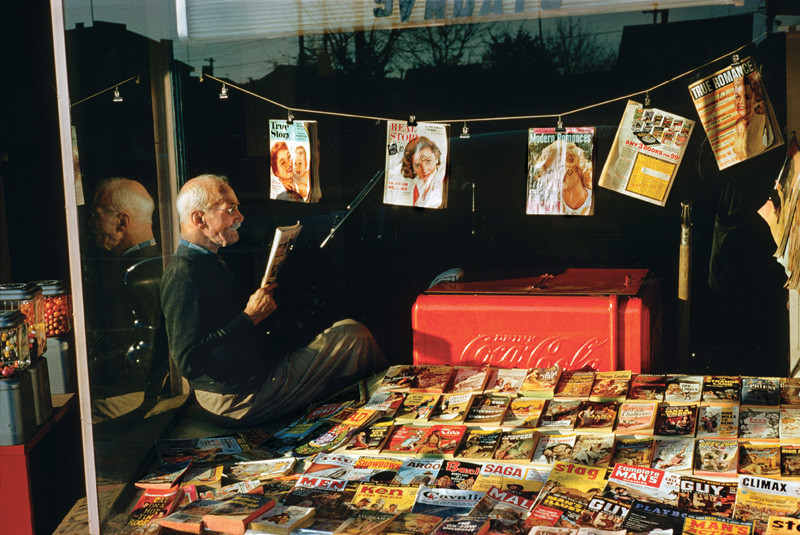

Herzog’s scenes are often animated by the presence of words read through the language of graphic design, creating a play of surface and space. This fascination with conventions of display is evident in his many photographs of display systems in windows, the taxonomies of second-hand stores, and the ordering system of a magazine stand in which Real Story is beside True Story and Mad lies next to Crazy. It is the idiosyncrasies of a handwritten sign or an array of goods that speaks of the particularity of locale. As he has said,

“The photo-realist hopes to discover unseen treasures, picturesque disorder, over-the-top nasty disorder, naïve art by housewives and gardeners, decay of all descriptions, and the multicoloured results of misdemeanour, if not crime.”1 His sharply observed documents propose that there might still be a way to make sense of the disorder and layers of information. Drawn to the collage aesthetic of disjunction, he allows the disparate and eclectic to address one another.

With a deep affection for the vernacular and a keen eye for detail, Herzog is drawn to the outmoded and discarded. His pictures of cultural artefacts – buildings, décor, menus, clothing, tools, magazines, and ways of life such as selling fish on the sidewalk – form a type of archaeology. There is an elegiac mood to his prosaic scenes that makes them seem to be caught in history. Anticipating collective urban memory, they are vulnerable to a nostalgic reading, yet Herzog avoids any glorification of the past or desire for historical continuity. Rather, he is an engaged participant who records specific moments as lived experience. The detritus of consumer culture is seen as a natural condition generated from entropy, from change itself. It is the chaotic energies and the disjunctions of old and new that drive the city’s vitality. The subject matter of Herzog’s pictures amplifies the notion that street photography is a series of shocks and collisions. As a field study about a place, his photographs are reminders of how we understand place as a genius loci.

Herzog’s images have a descriptive clarity and immediacy, but he does not insert his emotion, quite different from the skewed perspectives and expressive techniques of many of the street photographers of his time. While he is an admirer of Robert Frank, Herzog is more of an eagle-eyed observer at a slight remove who waits for the raking light of late afternoon or an expressive bodily gesture. His understated point of view is closer to the documentary style of Walker Evans, although Herzog is decidedly positioned in the scene. By giving every element equal value, his pictures breathe and welcome a search through the field of dense information.

Within the focused singularity of his extended project, Herzog has embraced considerable experimentation, not the least of which is that from the beginning he chose to work primarily in colour and developed new techniques for exploring its formal qualities. In the 1950s, colour photography in a documentary style was not yet considered an art form, and it wasn’t until the late 1970s that it began to be shown and collected by museums. Thus, it could well be said that Herzog is an important pioneer in colour photography. The fact that he has only recently been acknowledged as a notable photographer perhaps says more about the belated impulse to canonize western Canadian art, especially a narrative of art photography, than about a provincial condition. Geographic isolation has not prevented him from being well informed about current art photography and literature. It is also significant that as the histories of photography become increasingly expansive and international. Herzog was known as a medical photographer and teacher of photography who occasionally had shows over the years, but his practice remained unarticulated until recently, and to a large extent it is still inaccessible today, with thousands of slides yet to be unpacked from boxes. He favoured slide shows over cumbersome and expensive printing processes, and it is only now, with digital printing techniques, that he can produce photographs equal to the richness of slides. His remarkable body of photographs asserts that the value of a highly personal, methodical study of a city, unimpeded by the demands of clients, time constraints, or artistic dictates, can far exceed that of official historical documents.

Helga Pakasaar is a contemporary-art curator based in Vancouver. She is presently curator at Presentation House Gallery, where she presented exhibitions by Fred Herzog in 1986 and 1994. Her projects have often featured historical and contemporary photography and media art. In addition to an ongoing independent practice, she has been curator at the Art Gallery of Windsor, Ontario, and Walter Phillips Gallery in Banff.