[Summer 2008]

Cicero Galerie for Political Photography, Berlin, Germany

November 20, 2007 – January 18, 2008

The interest in the exhibition Made in Tehran: Six Women’s Views was immense. This is not surprising with photography by artists who call themselves “the children of the [Islamic] Revolution.” They are the next generation, after Shirin Neshat, and work in Iran, articulating urban life as they know and live it – in photo series. I was struck by their youth when I met three of the women in Berlin, and I wondered what makes their art so strikingly mature.

I asked Mehraneh Atashi how she was able to enter a traditional masculine powerhouse, the Zourkhaneh, where Persian heroes and clerics are venerated, combined with physical workouts and Sufi dances, for ecstatic experience. “I persisted, even after repeated rejections, until I got permission,” she said. “We have to fight hard to achieve our goals.” Clearly, persistence to claim a feminine space in a patriarchal society drives these women’s art. But so does the desire to attract Western viewers and collectors. Their exhibition history outside Iran is impressive; not so at home. Atashi brought into the Zourkhaneh a large framed mirror beside her analogue camera and photographed the men’s reflections, and with them her own. The resulting Bodyless: Selfportraits (2005) are an attempt to break what Pierre Bourdieu called the habitus, those embodied rituals by which a given culture sustains belief in its own obviousness, its ideology. The men, interestingly, allowed entry only after the artist explained that she would not photograph them, but their mirror image. Once she was wrapped in a long black scarf, nothing stood in her way.

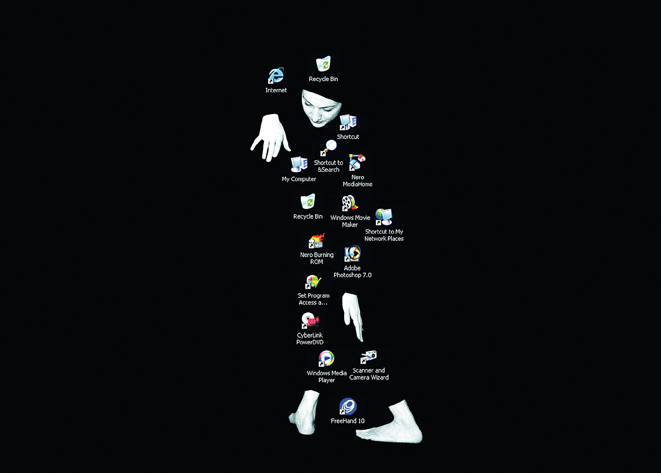

“The headscarf worn in public by Iranian women should not be understood as a separation device,” argued the German-based Iran scholar Katajun Amirpur during a panel discussion at Cicero Galerie, nor is the chador a symbol of oppression. This black dress, worn by the dancer in Shadi Ghadirian’s eight digital photos ctrl+alt+delete (2006), is delightfully adorned with computer screen icons.

The icons change in each photograph, becoming a dancing partner in one, where they are held in tight embrace, and building a ladder in the next. Their artistic usage is an iconic attempt to emphasize the artist’s online connectedness. Equally, they function as ideograms, rhetorical substitutions for a female voice, muted here, but clearly heard and understood. Michael Wamposzyc, who visited Tehran last summer, said that online exposure is very important since few exhibition venues are open to non-traditional art; however, access to YouTube is blocked. Importantly, Ghadirian manages the first Iranian website for photography www.fanoosphoto.com.

Photography is currently the preferred medium by artists in Iran. Ghazaleh Hedayat’s Peephole (2006) photographs critique the activity of the Islamic watch committee, omnipresent in cities, ready to blame and punish when the public feminine dress code and other laws are challenged. Perhaps to avoid their wrath, Hedayat photographed her own passport – fingerprint, script, parts of her scarf-wrapped face, and her apartments’ interior – to make us see just as the spy would see with one eye pressed to the keyhole. With a 35 mm camera, she created engaging black-and-white close-ups that blur subject and object and are of a size related to the radius seen by the spy.

Similarly, Hamila Vakili uses pictures of herself, but they are secondary to a process of digital montage. Untitled (2006) combines her passport photo and other body fragments placed against an old, crumbling stone wall that is loaded with symbolic potential.

In a genealogical pursuit, Gohar Dasthi rephotographed family photos taken in the 1960s and 1970s, and presented them in the Khanevadegi Ziyarati series (relating to family and pilgrimage, 2006). They provide glimpses into a pre-revolutionary Iran, its customs and dress, unknown to the artist. Remarkable in the older photographs is the handwriting on the front to describe, locate, and date. One, which Dashti reproduced, is of a woman; the script reads (in translation): Pregnant with Effat, 1962.

Contrasting with these black-and-white images of the past, Newsha Tavakolian’s poster-sized Untitled (2007) photographs focus on contemporary life, framed as if in passing, like news items. They take us into city streets to see women with blond-dyed hair and heavy make-up, their headscarves about to fall off, walls covered with pictures of martyrs who fought against Iraq, women in a café filled with cigarette smoke, Shirin Ebadi returning with her Nobel Peace Prize, and a child bride in her wedding gown. This beautiful but sad picture reminds us that girls are married at a young age in Iran, particularly in rural areas. Although the marriage age has been legally raised from nine to thirteen, said Amirpur, who spoke of the emancipatory effects of the Revolution, including an increase in literacy. Iranian women, she insisted, are self-aware and proud. This was conveyed in the Berlin exhibition, in which densely inscribed visual fields expressed more than words can say about the artists’ intentions.

Maria Zimmermann Brendel holds a Ph.D. from McGill University and works as an art critic in Berlin.