[Summer 2008]

by Sylvie Parent

Thanks to the growing popularity of digital cameras, with their direct connectivity to computers, the number of images sent by e-mail and of photographs published on the network has been growing exponentially.

The rapid appropriation of these technologies by the public has given rise to increasingly widespread activities such as sharing digital photographs and the production of image-laden personal Web sites.

The value of evidence often wins out over aesthetic research, with visual crudeness playing curiously in favour of authenticity and thus strengthening the documentary aspect.

Personal sites, usually text-heavy when the Web was in its infancy, were gradually populated with images, as photography rose to prominence among the practices that document the lives and thoughts of their authors. More recently, blogs and photo blogs (as well as video blogs, or vlogs) have extended the phenomenon of self-exhibition that photography helps to sustain. Over time, the peer-to-peer movement intensified and sites that are now called Web 2.0 went dynamic, constantly being updated as a participatory architecture, responsible for new networks, has come to the fore. Of course, artists were among the first to discern these trends, reflect on their effects, and exploit the possibilities to expressive ends.

Some art projects, such as Timothée Rolin’s ADaM-Project (www.adamproject.net), are based on precisely these phenomena. This site documents the smallest daily events and movements of its author and other participants. Visitors browse the project – one day at a time or by “find next” keywords – by alternating among the lives of one or another of these people, to the point that it becomes difficult to identify who is the creator of each image. The photographs, many of them banal and devoid of aesthetic research (rough framing and lighting), end up resembling each other. Thus, the project highlights the universal nature of these ordinary daily moments, while bringing out the democratic aspect of photography and the Internet.

It is relatively common for photographs on the Internet to be deliberately crude. Dissemination and access often take precedence over the image’s resolution or visual qualities. In this environment, the value of evidence often wins out over aesthetic research, with visual crudeness playing curiously in favour of authenticity and thus strengthening the documentary aspect. In effect, these photographs could very easily have been “improved” digitally with the use of publishing tools; their offhand appearance thus constitutes a sort of guarantee of their value as documents.1

The over-abundant publication of photographs on the “collaborative” Web – in photo blogs and on sites more specifically focused on archiving – engenders huge databases that are easily accessible and malleable. These new collections, which anyone may augment or modify, are now part of a collective archive in continuous development. A number of artists have appropriated the databases and diverted them from their habitual use, particularly those composed by the Google Images search engine and the Flickr photograph archiving and publication site, or even the images published on eBay and other commercial sites.2 One eloquent example of this tend is Subvertr (http://www.subvertr.com/), developed by a collective, an initiative obviously inspired by Flickr and with the objective of corrupting the usual exploitation of this type of site.

The French artist Christophe Bruno has produced a number of projects that make use of Web tools, especially the Google search engine. For instance, in Non-Weddings (http://www.iterature.com/non-weddings/), two images extracted at random from Google Images according to keywords chosen by the viewer are forceably melded. This generative work gives rise to unexpected couplings, sometimes humorous and usually incongruous. The resulting visual disparity highlights the difficulty of making relationships, and thus creating meaning, from the motley content of these collections of digital images.

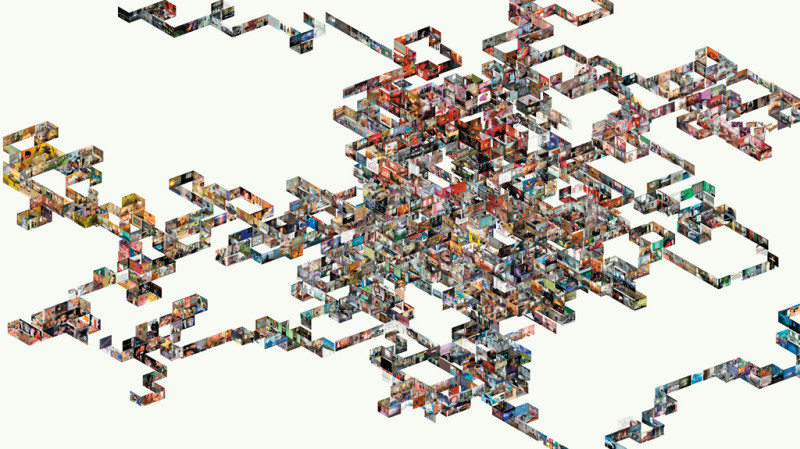

The desire to structure this mass of images and thus provide it with semantic value is at the core of many projects. For instance, Marika Dermineur and Stéphane Degoutein’s Googlehouse (http://googlehouse.net/) turns to architectural metaphor and proposes to construct a house with images drawn from requests made on the search engine. Lined up beside each other, then arranged on a bias to produce an interlocking effect, these views of interior designs (attached to many other elements found by chance through a random search) compose an endless labyrinth that does not manage to offer a coherent structure, instead showing the confusion resulting from such abundance. The uninterrupted sequence of surfaces only accentuates superficiality, to the detriment of the interiority that the motif of the residence might have conveyed.

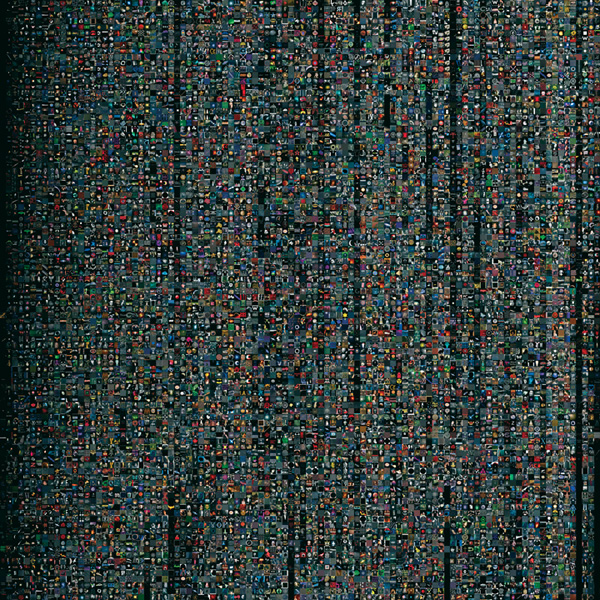

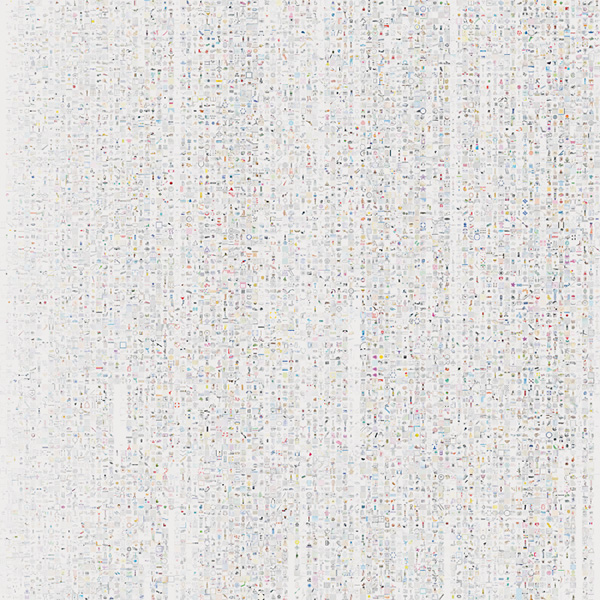

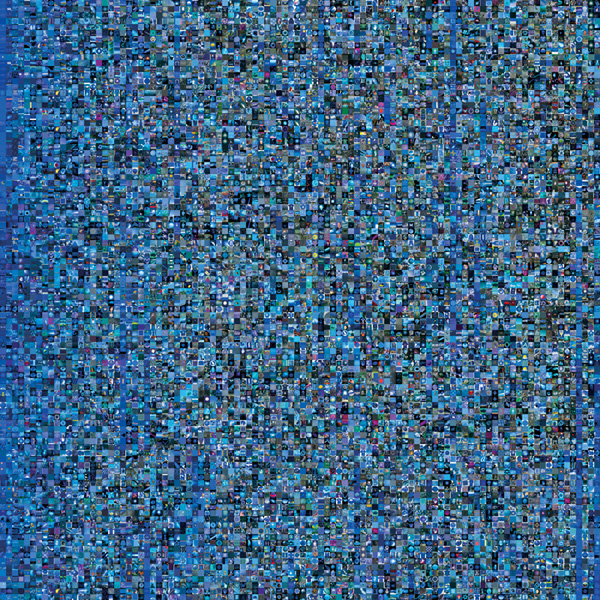

Reynald Drouhin draws on the same repertoire to compose monochrome mosaics in perpetual motion. In the generative project Monochrome(s) (http://www.incident.net/works/monochromes/), colour, in all its shades, acts as a reference but is not able to semantically unify these groupings; rather, it supports the great diversity of proposals that vie for attention. Ethan Ham’s Self-Portrait (http://transition.turbulence.org/Works/self-portrait/) is another attempt to harmonize enormous quantities of images, to find a common basis in them. In this work, face-recognition software associated with the Flickr site is used to find images matching a self-portrait of the artist. The visual analogies that result from this approach are surprisingly diverse. Unable to form a homogenous ensemble based on similarity, the project creates links among individuals of different origins and backgrounds.

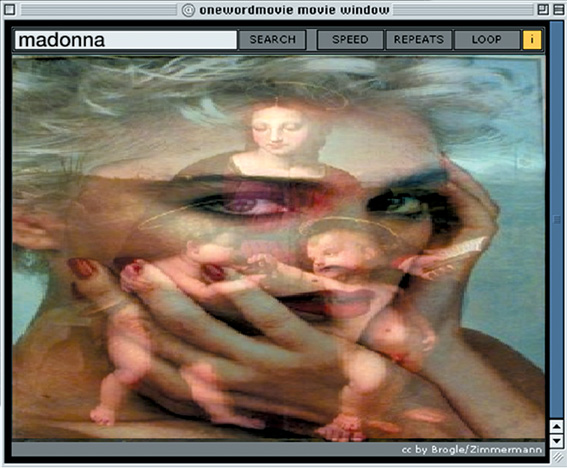

While these projects attempt to spatialize repertoires of images in order to make an intelligible visual ensemble, others choose instead a temporal structure – that is, a dynamic structure that engages the photograph in a sequence to approach a cinematographic experience.3 In One Word Movie (http://www.onewordmovie.ch/), by Beat Brogle and Philippe Zimmermann, a film is generated from a keyword used to extirpate images archived on Google Images. Yet, the dissimilarity of these samplings contradicts the impression of continuity, whatever the speed at which the images succeed each other and even though the sequence is organized in loops. The cinematic structure does not allow viewers to perceive a coherent whole. Behind this dissonant unfurling, the keyword, a unit with unlimited faces, leads only to a shift in meaning.

In Flickeur (http://incubator.quasimondo.com/flash/flickeur.php), Mario Klingemann also explores a dynamic form similar to film, looting Flickr and linking together images from various sources. The artist uses strategies inspired by cinema (slow motion, soft focus, cross-fades, sweeps, returns to images seen previously, superimpositions, etc.) that produce effects of continuity. The passive experience enables the user to view a strange, atmospheric film with playful qualities that may have certain affinities with experimental cinema. Ceux qui vont mourir (http://incident.net/works/mourir/), by Grégory Chatonsky, draws also on the very popular Web 2.0 sites YouTube, Flickr, and Experience Project. The project associates the confessions of some with the images of others to construct a series of interesting stories. The psychological value of the testimonies and the superimposition of the same texts on a number of images form transitions between fragments. In addition, the slow speed of the film encourages comparisons and contributes to the creation of semantic acts. Through these different aspects, the project offers a fluid portrait of the Web inhabited by its contributors.

Translated by Käthe Roth

1 The attraction of the false and the constructed is deeply felt in the many digital collages and alterations that characterize the images of our times. However, it seems that the digital photographs of recent years, which oscillate between reality and fabrication, have appeared mainly in print form. Thus inscribed in the same territory as silver prints, they seem to stand apart from the documentary heritage by highlighting this tension in the image. In fact, when the image remains in the digital environment and forgoes printing, the integrity of the photograph is constantly tested in an obvious way, and this is why its value as testimony is a sought-after quality.

2 See, notably, eBay Landscape (http://www.zanni.org/ebaylandscape/ebay.html) by Carlo Zanni. The work uses data (eBay stock diagrams for the mountain and images published by CNN for the trees in the foreground) to produce a landscape the content of which evolves as fragments are gathered in real time.

3 With regard to the tension between the fixed nature of the photographic image and the dynamic environment of the Web, see Sylvie Parent, “Projets photographiques pour le Web: du statique au dynamique,” CV ciel variable, No. 76 (June 2007).

Sylvie Parent is an art critic and independent curator. She has written numerous essays on contemporary and neo-media art and curated exhibitions both locally and abroad.