[Fall 2008]

Galerie Simon Blais, Montreal

February 27 – March 29, 2008

Although we can still see the etymological relationship between the modern term “technology” and the ancient Greek word techne, nowadays we generally lose sight of its original meaning – art, craft, skill. Éliane Excoffier’s latest show at Galerie Simon Blais reminds us that aesthetics and technology go hand in hand. A student of art history, this basically self-taught photographer devised more or less her own technique, which returns to the roots of photography but incorporates twenty-first-century criteria. This Janus-faced approach infuses her work with tension and intimates that beauty remains primordially conflictual.

In this light, we perceive the metaphysical significance that she attributes to black-and-white photography. Not merely an art form, it also constitutes, for her, a spiritualist medium – and this should not surprise us if we remember that the mystical founding editor of Aperture, Minor White (1908–76), considered photography a “way” to spiritual enlightenment. In this vein, the Musée régional de Rimouski invited Excoffier to participate in its upcoming show on spirit photography, an art movement from the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries associated with spiritualism – a belief that the souls of the dead communicate with the living. In fact, Excoffier counts herself among those today who endeavour to capture spirit images, a trend that parallels recent developments in thanatology – the multifaceted study of death and dying.

Excoffier’s worldview thus dovetails with the innate dialectics of black-and-white photography. Indeed, a field of vision in which all colours ultimately appear as shades of grey facilitates the notion that the quick and the dead alike inhabit a neutral shadowland, in which the grave loses its victory and death its sting. In this twilight, people seamlessly fade in and out of presence and absence, corporeality and spirituality, expression and silence, movement and stasis, life and death. Such perpetual oscillation evokes the liminality of our existence.

Further, Excoffier’s tableaux bespeak a coherent narrative of the human drama. Despite postmodernism’s grandiloquent discourse about “paradigm shifts,” our tragicomedy most often unfolds incrementally, rather than by leaps and bounds. Likewise, the theatre of our lives resides rarely on mountaintops, but instead usually at the myriad interstices that we overlook amidst the hustle and bustle of day-to-day living. Its details furnish the backdrop for Excoffier’s scenes. She accordingly fleshes out her storyline through mundane phenomena – the texture of cloth, smudges on a mirror, creases in a plastic tarp, limp apparel, a run in nylons, coarse rope, wiry pubic hair, or the grain of mortal skin.

In short, she articulates the concreteness of both sentient and inanimate subjects so as to render them visually tactile. I therefore call her work haptic photography, because of its predilection for the sense of touch. However, by virtue of representing a tangible object through an intangible image, the photographic medium creates a shear between materiality and immateriality. Excoffier’s art results largely from her investigation of that crux.

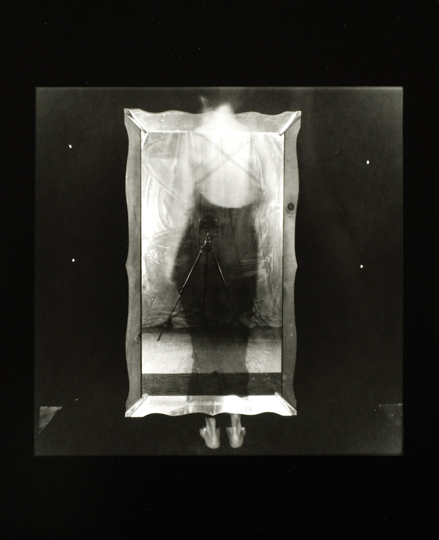

She photographs with a camera manufactured during the heyday of the Soviet Union, in the capital of Ukraine, Kiev – whence the name for this model of cameras and the eponymous title of her show. Kiev (1) sets the stage for the series by juxtaposing outdated technology and postmodern self-referentiality. The latter explains her frequent recourse to mirrors, which in this frame enable her to photograph her own index finger flicking the shutter of her vintage apparatus.

On the one hand, this picture takes viewers back to the late-Victorian era and the pioneering work of Eadweard Muybridge (1830–1904). Indeed, Excoffier candidly acknowledges the inspiration that she draws from his photographic experiments. Little wonder, then, that Kiev (1) depicts motion, the modus operandi of her still photography and the cornerstone of Muybridge’s scientific inquiry. On the other hand, this image evinces postmodernist preoccupation with the “gaze” since it features a camera looking us in the face. We might even have the unnerving impression of staring down the barrel of a gun aimed right between our eyes.

Kiev (II) portrays a scantily clad woman standing somewhat spread-eagle in what could easily pass for the back room of a seedy brothel. Excoffier thus introduces the erotic leitmotif of this series, which pursues yet subverts Muybridge’s scientifically sublimated eroticism. At the same time, she mocks the prim-and-proper mores of bourgeois studio photography, because Kiev (II) in fact pictures her unadorned workplace. Its conspicuous equipment makes viewers acutely aware of the photographic process – an effect that Excoffier admittedly seeks, and one in keeping with postmodern erosion of any sense that an ultimate end or meaning exists. More to the point, this photograph of photographing blurs the borders between representation and reality.

An independent scholar and translator, Norman F. Cornett explores the relationships among cultures, politic’s and religions. He publishes in American and Canadian scholarly journals, and leads workshops on the arts in both French and English.