by James D. Campbell

Over the course of the last few decades, the pressing issue of alterity – “Other” and “otherness” – has been admirably foregrounded in a number of disciplines and, with increasing frequency, in contemporary art practice and discourse. Arguably, the problem of the Other – that is, of human intersubjectivity and community – is a touchstone for understanding the art of our time.

It has been clear for a while now that the point of fulcrum for Luis Jacob’s art is this issue. Intersubjectivity, empathy, and the Other are all central to his thinking about art. His interest in a phenomenological and semiological understanding of alterity was probably inspired by his studies at the University of Toronto. He opens up new directions of understanding for what is one of the most fundamental concepts of human life in its societal context and within its intersubjectively shared horizon of meaning.

Jacob may be a gleeful scavenger of the image-multiplicities endemic to our media-replete and exponentially expanding information culture, but he has developed an art of juxtaposition that master collagist Kurt Schwitters would have loved for its uncanny acuity and skill and Edmund Husserl would have admired for its model of constitution through a lexicon of images that affirms the existence of a common homeworld, whether one is Christian or Muslim, gay or straight, man or woman, black or white. Toronto-based Jacob has worked in a wide spectrum of media, including photography, performance, video, and interventions in public space. He has also worn with grace the alternating hats of curator, anarchist, theorist, and artistic lightning rod. His recent participation in Documenta 12 earned him a still wider public.

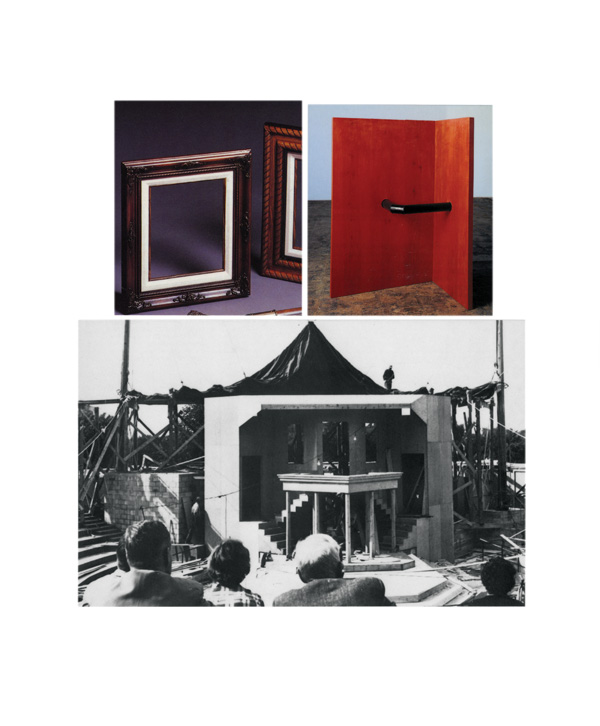

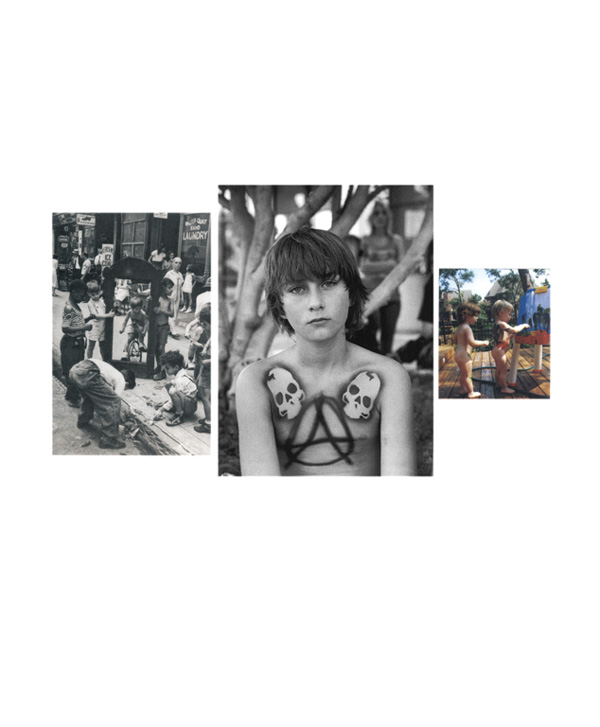

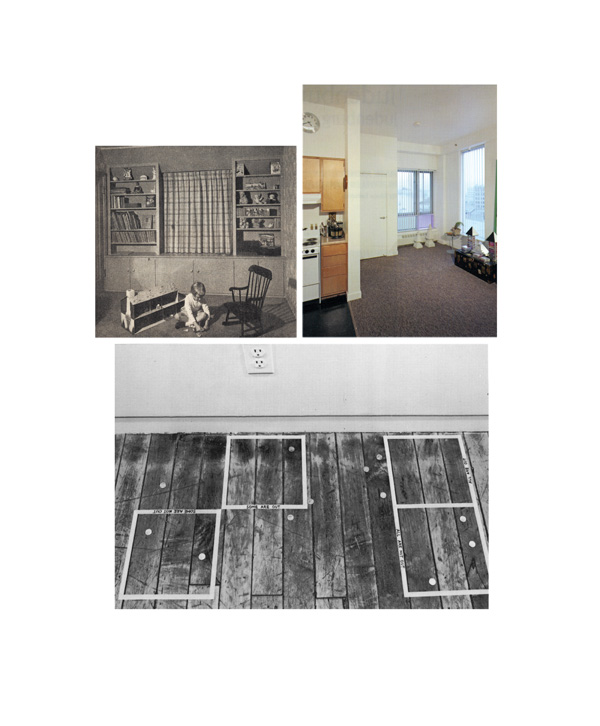

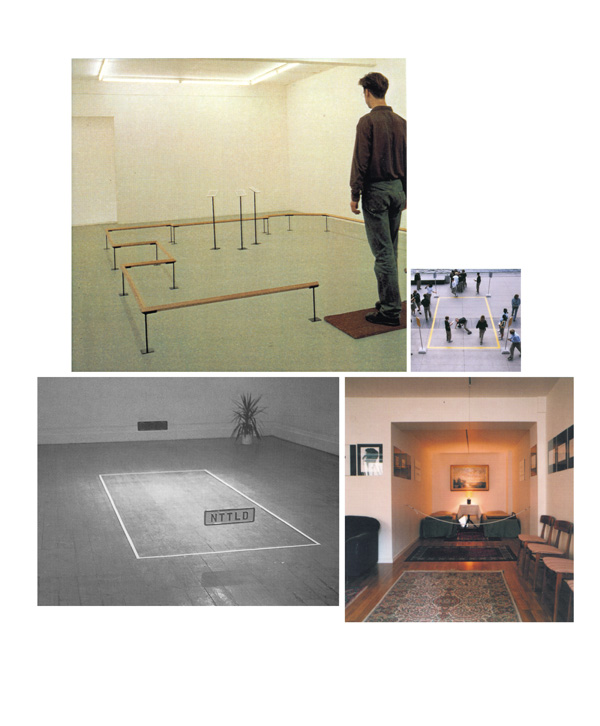

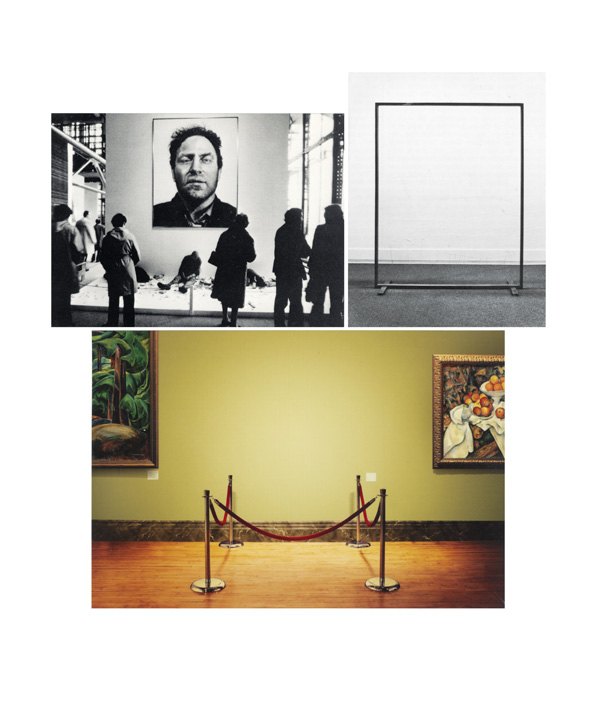

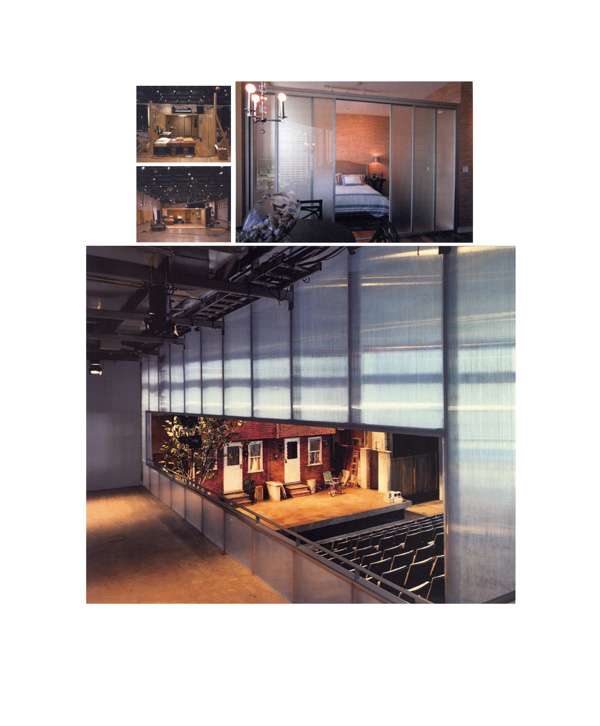

Pristinely installed at eye level in its own space on the top floor of the Museum Fridericianum, Jacob’s Album III (2004), like its successors, was a narrative magnet for the eye, sweeping it along at a hectic pace through 159 sequential panels like one continuous unfolding accordion-like photomontage on unframed sheets of plastic laminate. The archive, like all of the Albums, is constituted from sundry photographic images culled from news magazines, encyclopedias, and a host of other sources. On each 18″ x 12″ sheet, Jacob offers a selection of images that the viewer invests with a poetic logic and interaction that is mutable and phantasmic in its unpredictable peregrinations. Like a wily collagist, Jacob brings into proximity along the perimeter of the gallery space elements of an organically evolving cosmology, the reverberations of which are intimately felt.

The conceptual logic of the images in Jacob’s Albums, independently and in concert, is eventually discoverable. As one moves successively from one concatenation of images to the next, this strange logic, surreal yet necessary, becomes almost incantatory, like prayer. Here, the lifeworld is composed of fragments that speak eloquently of wholes and wholes that speak eloquently of parts. At a certain point, the perceived wealth of images, which never becomes surfeit whatever the superabundance, results in an appreciation of Jacob’s feeling for alterity and his utopian dream of ennobling a constituting intersubjectivity in and through his archival work.

In Album VI, Jacob’s latest instalment, what seems upon first inspection a systematic and conceptual artwork soon morphs into a deeply personal and unpredictable take not on the image detritus of the object world but on the subjectivities that inform, order, constitute, and effect it. The linked series of found images expands beyond the physical limits of the installation itself1, an untidy garden blossoming outward, into the lifeworld.

Likened by some critics to related works by artists such as Hanne Darboven and Gerhard Richter, Jacob’s pristine installations stake their own claim, and are phenomenally resistant to the most viral strains of objectifying taxonomy. If there is a casual authority at work here in the juxtaposition of images, Jacob is admirably devoted to meticulousness and associative “rightness” that defeats any sense of overarching classification. What emerges from the “white noise” of the images in his Albums is a certain utopianism. With a sneak peek at sundry tomorrow worlds all capable of being formed within the shared horizon of human intersubjectivity, Jacob reveals the humanism that lies beneath the surface of his work, behind his anarchist beliefs.

With its juxtaposed, streaming images of humans interacting, architectural facades, artworks, furnishings, and so forth, Jacob has created in all of his Albums, but in Album VI most specifically, an amazingly profuse vision of humanity at work and play that offers a fine and replete portrait of the human lebenswelt. His uncanny knack for modular image montage opens and widens the horizon of intersubjective understanding inside his work and achieves self-presence there. All of the albums add up to a phenomenologist’s wet dream of the social world. After all, one of the principal themes of transcendental phenomenology, and some would say the most important, is intersubjectivity itself.1 Husserl held that intersubjective experience is as essential to the constitution of the other person as it is to the constitution of the self. And, in fact, he argued that it is fundamental to the constitution of the objective spatiotemporal world. The constitutive achievements discussed in transcendental phenomenology find their perfect artistic mirroring in Jacob’s restless archive.

The perceived wealth of images, which never becomes surfeit whatever the superabundance, results in an appreciation of Jacob’s feeling for alterity and his utopian dream of ennobling a constituting intersubjectivity in and through his archival work.

Intersubjectivity, in the first person, means, of course, empathy.2 Jacob is no epistemological foundationalist; he is an empathic ethnographer of the near and the far – and it seems clear that he is attempting to organically grow an imagery-rich replica of our lifeworld with an eye toward widening the horizon of human understanding. One might argue further that Jacob has methodologically practised a form of iterated empathy, at the level of and through the language of gathered images; he puts himself out on a limb so that we might join him there, whether in solidarity or in startled wonder.

Jacob is interested in furthering the cause of intercultural understanding, and his archive represents a significant imagistic extraction of our everyday lifeworld as composed in and beyond the realm of pure appearances. This is a welcome opportunity to experience a parallel stream of epiphanies in the seeing. So, if Jacob’s conceptual art practice seems to evince a taxonomy that the very grid-like structure of his images reinforces on one very superficial level, it is negated on deeper levels, in which image play and resultant recombinant interplay constitute a continuing reiteration of the utopian principle.

Jan Verwoert wrote about Julius Koller, “His is a radical optimism, his archive is utopian, Friedrich Nietzsche argued that to realize a fundamental critique of ‘bad faith’ means to move beyond cynicism and embrace a radical optimism that exceeds the petty dialectics of expectation and disappointment.3 Verwoert could just as easily have been commenting on Jacob’s work, marked as it is by a kindred radical optimism both authentic and deeply felt. Like Koller’s, Jacob’s gestures are those of anarchistic defiance and bids for utopian free-thinking, intersubjective communication, imaginal migration, and community-mindedness. These heartfelt gestures transcend the bad faith of some of his critics, who speak of “embarrassment” but instead demonstrate only their own myopia. We should be mindful that not only is going out on a limb central to Jacob’s philosophy of art and life, it is also utopian thinking at its most transparent, riskiest – and most moving. Instead of reviling Jacob for wearing his heart on his sleeve, perhaps we should all write him an open-ended I.O.U. for pricking our social conscience with the triad of constituting intersubjectivity, radical optimism, and utopian thinking that is at the proverbial heart of his art.

If Martin Buber was correct that human nature is well and truly embedded in human communities, and that our very nature is grounded in and inseparable from communitas and a constituting intersubjectivity that makes the world possible, we should be grateful to a free-thinker such as Jacob, who deepens our humanity through an archive that is all about what it means to be human, and continually reminds us that we still are. His art is utopian in the best sense of that word – the fervent desire to change the condition of being here and the ardent striving after a new and better world.

Jacob’s previous series, Album III, was on view at the Musée d’art de Joliette during the summer of 2008.

Luis Jacob is a Toronto artist who works in a variety of media. His work was recently shown at the Barbican Art Gallery (London), Documenta 12 (Kassel), the Kunstverein in Hamburg, the Morris and Helen Belkin Art Gallery (Vancouver), the Biennale de Montréal 2007 (Montreal), the Power Plant Gallery (Toronto), and the Musée d’art de Joliette (summer 2008). He was previously involved in the community-education collective Anarchist Free University. Jacob is represented by Birch Libralato, Toronto.

James D. Campbellis a writer on art and independent curator based in Montreal. The author of over 100 books and catalogues on contemporary art and artists, he contributes frequently to Ciel variable, BorderCrossings, Canadian Art, Etc., C., Modern Painters, and Contemporary, among others. His most recent selected publications include essays on David Blatherwick (Windsor Art Gallery), John Heward (Musée du Quebec), and Janet Werner (Parisian Laundry, Montreal), all in 2008.

1 Constitutive intersubjectivity is brilliantly discussed in the fifth of Husserl’s Cartesian Meditations and in the manuscripts published in vols. 13–15 of Husserliana (The Hague: Nijhoff, various dates).

2 See Edith Stein, On the Problem of Empathy (The Hague: Martinus Nijhoff, 1964) (orig. publ. 1917). This was the text of Stein’s Ph.D. dissertation on empathy, supervised by Husserl.

3 Jan Verwoert, “Obituary: Julius Koller 1939–2007,” Frieze, No. 111 (Nov.–Dec 2007).