[Spring 2009]

Leonard and Bina Ellen Art Gallery Concordia University, Montreal

October 23–November 29, 2008

Curator: David Tomas, with the collaboration of Michèle Thériault and Eduardo Ralickas

The commingling of academia and art in Tim Clark’s conceptual practice is announced at the outset of his recent retrospective exhibition with the installation of a small shelf of books on the entry wall. Including titles by Georges Bataille, Ludwig Wittgenstein, Cormac McCarthy, and Danny Lyon and books on ethics, conceptual art, and feminism, the collection also serves to distil the principal themes and discourses filtering through Clark’s work: its analytical and retrospective leanings, its interest in issues of language, and its limits – in art and other “forms of life” –questions of relativism, ethics, and morality, the relationship between valour and violence, and the psychological and social structures that shape identity and relations of power. That the retrospective will be challenging is clearly enough stated with this opening salvo; that an exhibition almost entirely built of textual materials will be so deeply and emotionally affecting is what surprises the viewer by the show’s end.

Elegantly abstracted, book and texts proliferate here as artefacts dramatically embedded in sculptural objects and installation works or as texts read aloud in performance pieces – the latter represented in the retrospective via photographic and video documentation. With the presence of hand-typed and paginated descriptions written by the artist and placed beside each artwork, the exhibition itself seems rather book-like.

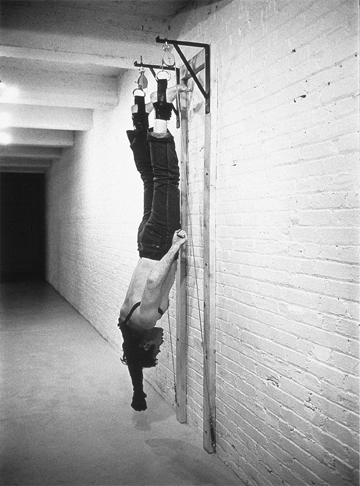

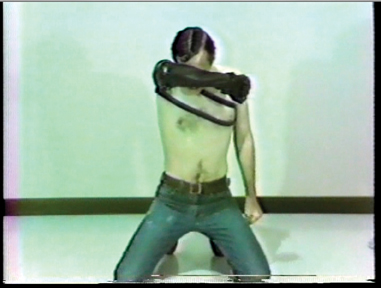

Although textuality is a defining characteristic of conceptual art, few projects have been as directly concentrated on the problematic of “reading.” A Reading of “On Obedience and Discipline” from The Imitation of Christ, by Thomas a Kempis (1978) and A Reading from The Bikeriders, by Danny Lyon, Cal., Age Twenty-Eight, Ex-Hell’s Angel Member, Chicago Outlaws (1979), two of the many early performance works that took their names from literary titles, typically involved some manner of recitation. Narrated in a “truncated,” excessively halting style, or read loudly and deliberately so the audience could hear the words distinctly if the readings were hard to comprehend because of the complexity of the material “quoted,” they were even harder to withstand because of the more or less overt violence that permeated the spectacle. Highly affected recitation functioned in the original performances, as it functioned again in the recent exhibition’s loops of video documentation, to amplify the disquiet established by other production elements – the notorious black leather gauntlet that Clark often wore in his performances (pictured rather than presented in the retrospective), and the tortured actions and positions that he endured over the course of each presentation. Blindfolded, suspended upside down, or pressed against the wall, Clark never simply read the words so much as embodied them.

Deliberately confrontational and unsettling, the pieces were meant to establish a boundary line or limit point between artist and audience, one that would also, more significantly, echo the different worldviews of writer and reader. To press recognition of the irreconcilable realms of experience and value systems that exist between individuals and communities is to promote an understanding of the limits of knowledge and language at its most basic level. To do so in highly charged and frequently shocking performance works is to emphasize the violence implicit but not often recognized in the acceptance of relative worldviews. Such insight is probably easier to grasp in performances whose texts are graphically violent or sexual, although in one way or another all of Clark’s work attempts to circumscribe the inherent contradiction and conflict between, but also within, different systems of belief.

The works that address conflict internal to certain ways of life are some of the most moving in the exhibition. Although differently, works such as John 15: 2–3, An Anonymous Letter (1981) and Melancholy of Maleness (1996) speak poignantly to the kind of sacrifice that attends submission to social identifications whose internal contradictions are impossible to reconcile. In both works, values of heroism and acts of savagery are presented as mutually supporting and defining terms. By way of its spatial arrangements, An Anonymous Letter, an installation work, forces the viewer to identify with an infantry soldier heralded in a letter from Soldier of Fortune magazine for selfless and blind heroism, “a man [who will] lay down his life for his friends,” to quote John 15, but whose brutality in war is always reviled.

Melancholy of Maleness considers the double-edged sword of such subjection somewhat differently and quite literally. In fact, the sculptural object built from a pair of bayonets that accompanies the series of photographic works suggests another level of conflict for the masculine subject in a postmodern, post-feminist era. Adopting a phrase borrowed from feminist Shulamith Firestone, the title speaks to the psychic impact of shifting symbolic values. The imagery, which juxtaposes black-and-white documentary photographs of museum displays with diptychs isolating the iconography of masculine cultural authority in a painting by Nicholas Poussin, not only suggests the wreckage of a masculine subject position cast asunder, but the ruins of all associated ideals – of guardianship and heroism, service to the greater good, and greater good itself.

Clark’s last work, a feature-length video titled A Reading of Cormac McCarthy’s “Blood Meridian, or the Evening Redness in the West,” by the Southern, American Author Comac McCarthy (2003), engages McCarthy’s hyper-violent, revisionist history of the settling of the American Southwest as a neo-Manichean parable about the necessary correspondence between invention and barbarism in the making of the modern world. In a manner similar to that adopted in early performance works, and to similar effect, Clark pairs the reading of three chapters from the book with performative and filmic responses to the text. The video begins with a highly abstracted interpretation of violence and ends with an image that renders the legacy of the colonial violence described in the text in more concrete and scornful terms. The last thirty minutes of the video includes a continuous shot of a contemporary wilderness, an endless highway of retail malls, hotels, and big-box stores.

As the show’s curator, David Tomas, notes in the exhibition catalogue, the period of Clark’s “limit-based” art production parallels that of the institutionalization of conceptual art within the university and also the spectacular rise in its market value. Although Clark’s project has flourished within the university setting by pushing the boundaries of scholarship up against those of art, and vice versa, the artist stopped making art in 2003, finding the competing values of critical art production and marketplace difficult to reconcile. He will be missed.

Cheryl Simon is an artist, academic, and curator whose current art and research interests include explorations of time in media arts and collecting and archival practices in contemporary art. She teaches studio arts at Concordia University and cinema + communications at Dawson College.