[Summer 2009]

OCAD Professional Gallery, Toronto

March 5 – May 31, 2009

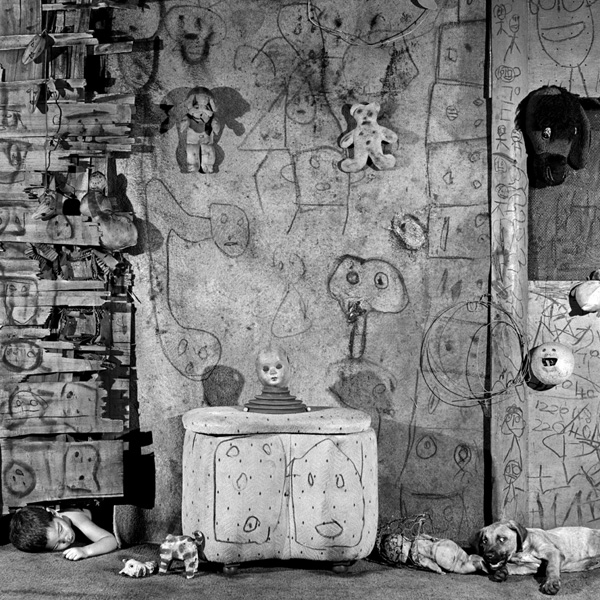

Everything is decay in Roger Ballen’s photographs: floors, walls, toothless mouths, and lank, rancid hair.

Their only “beauty” (as we warily call it) – purloined from painterly, graffiti-wired photographs of the past (Siskind, Brassai, etc.) – is inventively and mercilessly imposed, in the pictures, upon misery and rueful wonder. Ballen’s carefully calculated passages of calligraphic joy (the kind of thing that Australian curator Robert Cook, writing on Ballen’s Web site [www.rogerballen.com] calls “the drizzle and tilt of a wire, the shuffle of a shoe, the smear of sand on a wall . . .”) always pull you in, all the while lacerating you with what often feels like your voyeuristic retreat from the urgencies of social conscience.

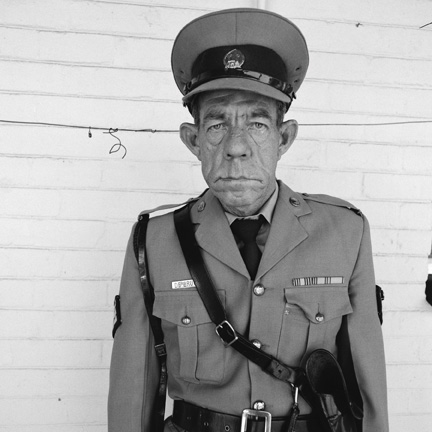

Ballen, a white man living in South Africa, has been doing significant photographic work in and around Johannesburg since the late 1970s. For the photographs that were in his books Outland (2001) and the brilliant Shadow Chamber (2005), he gathered together subjects and settings (he has tended to work with a sort of prescribed dramatis personae, a repertoire of personages/actors, in the style of Ingmar Bergman), disposing them in increasingly claustrophobic spaces. These spaces feel remarkably like stage sets (his para-dramatic theatres of stasis are frequently compared to Beckett plays in progress). “It is difficult to explain this place [i.e., the hypothetical place that is his Shadow Chamber],” Ballen has noted, “except that it exists in some way or other in most people’s minds.”

With his new Boarding House (2009) – copies of which, at time of writing, were still steaming across the Atlantic – Ballen has almost entirely withdrawn the full figures of humans and of the animals that lent such urgent sub-consciousness to his earlier images— from his photographs. He allows them all back in again, but this time only as fragments.

In the almost seventy photographs in Boarding House, which are the subject of a bracing and moving new exhibition at the Ontario College of Art and Design’s Professional Gallery, there is a kind of withdrawal of – or at least a porosity within – what might be called the political field of the photographs: now, Ballen seems to be in the process of exchanging documentary poignancy for an increasing preoccupation with the unlikely juxtapositions of textures and objects so beloved of the surrealists.

Of the photographs in the OCAD exhibition, only four offer a whole figure. “Over the past 30 years,” writes the exhibition’s curator, Charles Reeve, in the brochure accompanying the show, “[Ballen] has framed his images more and more tightly, moving to photographing exclusively indoors and thus eliminating context while emphasizing detail, to arrive at vibrant yet disconcerting scenes that could be anywhere.” Where they could be, for the most part, is on some irrational terrain inextricably linked with the umbrella/sewing machine/operating table interiorized intensities of the Comte de Lautréament and the canonical surrealists.

In essence, Ballen is making photographic still lifes.

But lest this sound like a retreat from imagistic urgency, it is eminently clear that these particular still lifes, though “still” – or “morte” in the sense of a seizing-up of silences – are as brut as any of his photos: the parts of his people and creatures that end up in the works are as destabilizingly metonymic as partial plaster casts. The white rats with their heads in a flower pot in Stalked; the boy with the unfurled accordion that echoes the white wingspread of a dead chicken in Eulogy; the man, wrapped like a parcel, huddled in the corner of Cornered; the dead wild boar in Celebration, surmounted by four upraised hands like puppets in a Punch ’n’ Judy show; the cropped hand holding onto a rat’s tail in Predators – all of these truncated presences are a kind of cultural detritus (which my dictionary defines as “a product of disintegration, destruction or wearing away”), which, even greater in emotional impact than the societal “dramas” that came before, function in the photographs as objective correlatives, vectoring us toward the spiritus mundi, the image bank, that, as Ballen has ventured, “exists in some way or other in most people’s minds.” These fragments, if I may misuse T. S. Eliot for a moment, Ballen has shored against his ruins.

The rest is drawing, the insistent articulating of calligraphy: runic marks and primitive pictures scraped on walls and furniture, purposeless loops and twists of wire hanging down, rips in filthy cloth, blistered paint, rusty tins, torn zebra skins, stained sheets – this is the bottom-feeding life as lived, unrepressed and fearful/fearless, in the basement of the mind, as lived in the eternal Lascaux caves of the unconscious.

Toronto writer, critic, and painter, Gary Michael Dault is the author of ten books. His art review column appears each Saturday in The Globe & Mail.