[Spring 2010]

Here are selections from a remarkable documentary work produced by Hu Yang, a Shanghai photographer who recently moved to Toronto. Shanghai Living comprises some five hundred portraits of Shanghai residents photographed in their own interiors, along with short excerpts from interviews in which each describes his or her way of life, values, and aspirations. The overall result is a fascinating glimpse into this city of almost twenty million inhabitants, where all the contrasts in China are found: accelerated modernization and Westernization, growth of the middle class and consumer values, stagnation of the most humble living conditions, and mixing of cultures.

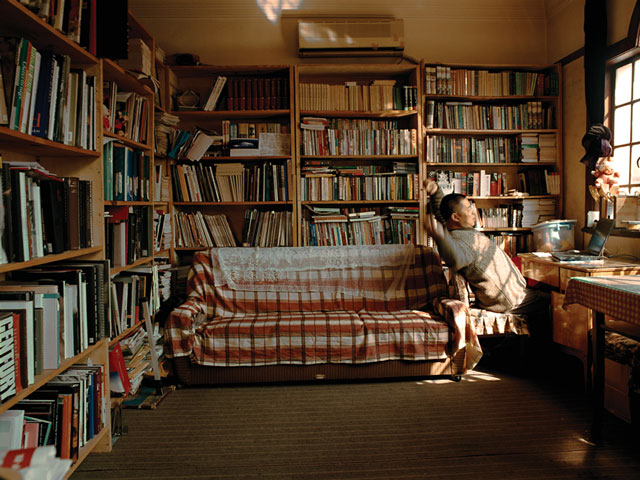

Hu Yang, Tang Jinsheng (de Shanghai, travailleur à la retraite). © Hu Yang

杨文金 (四川籍 民工)

沈凤巧 (江苏籍 民工)

出来打工,就是为了挣钱,生活过得好一点。但是挣钱,说的容易。我们乡下人

到上海这样的大城市里来想挣大钱,那是不可能的。我们干最苦,最累,最脏的活,

反而挣不到大钱。

Yang Wenjin (from Sichuan, labourer)

Shen Fengqiao (from Jiangsu, labourer)

I came to Shanghai to earn a living and have a better life, but people like me will never make big money in a city like Shanghai. We do the hardest, dirtiest, and most tiring work but will never make a fortune.

徐 颖 (上海籍 中专生)

我父亲早年去世,家里经济条件困难。我希望尽早的工作,改善家里的生活。

墙上贴的这些图片,都是我崇拜的偶像。我是追星族,崇拜许多文艺和体育明星。

XU Ying (from Shanghai, student at a technical secondary school)

My father passed away long ago and we have a difficult life. I want to go to work as soon as possible and help my family. I’m a big fan of movie and sports stars. All these [people in posters] are my idols.

薛松 (上海籍 画家)

工作时我喜欢安静,一个人画画时间长了挺闷的,所以常常和朋友泡酒吧,

聊聊天,喜欢热闹。以前年轻时单纯,没有责任心,穷得挺开心;现在有钱了,

想得多了,有了责任心,压力就大,反而没有以前开心了。还是最想画画,

是内心的需要。否则会觉得心里很空。只有画画才开心。我以前的愿望现在基本

上全达到了,因为要求低,没想挣它5个亿(笑)。还是淡泊的生活比较幸福。

身体不好,画不出好作品,碰到烦人的事时都会痛苦。随着时间的推移,痛苦也

就消失了。

Xue Song (from Shanghai, artist)

I like to work in a quiet environment. Sometimes, when I feel bored, I go to pubs with my friends to drink and chat. I didn’t know much about responsibili- ties when I was young and lived a poor but happy life. Now I don’t need to worry about money but feel responsible for many things, and it gives me pressure. I fulfilled all my previous wishes because they were simple and easy. I haven’t thought about having $500 million, and I think a simple life would be happier. I’m not in good health and can’t produce good works. I suffer from anxiety, but time helps soothe the pain.

魏玉芳 (山东籍 小贩)

我们的日子过得很苦,每顿都是煎饼就着咸菜吃,加上一杯白开水。孩子们想吃

荤菜时,就烧一个鸡蛋给他们吃。只要不下雨,就天天早出夜归,每天做十五、

六个小时生意。希望孩子们上好学,我那怕东借西凑也要让他们上大学,别象我

这样没文化。大儿子很争气,每学期都得奖回家,我很开心。外出摆水果滩被地

痞流氓欺负,让我伤心透了。

Wei Yufang (from Shandong, vendor)

We lead a hard life and have battercakes, pickles, and a glass of water for all three meals. When our kids want meat, we cook them an egg. We work more than fifteen hours a day if it doesn’t rain. We want our kids to be educated and not to live like us. I will risk anything for our kids to go to university. My eldest son is excellent and wins prizes every semester. I suffer from being harassed by local ruffians.

陈檬嘉 (上海籍 公司董事长)

我爱好广泛,生活丰富。打高尔夫球,游泳,听音乐会,与朋友一起喝咖啡,

聊天,还喜欢到世界各地去旅游。希望拥有一座庄园,养一匹良驹,我喜欢骑在

马上的感觉。过悠闲的田园生活。国内的人际关系太复杂,心理上有压力。

自己开公司也挺烦的,很累

Chen Mengjia (from Shanghai, corporate chairman)

I have many hobbies and a rich life. I play golf, swim, go to concerts, have coffee and chat with my friends, and travel. I dream of having a mansion and a horse. I enjoy riding horses and having a carefree life. Human relations are too compli-cated in China, and I’m stressed. It’s tiring to have your own company.

徐宗汉 (美国籍 品牌咨询)

我的生活融会了东方和西方,现代和传统。不做事就不开心,现在的生活又太忙乱。

在美国工作感觉没有在上海有意思。只是为了挣钱,对社会没有意义。我骨子里是

一个中国人,总希望为中国做点什么。把美国的好东西与中国的好东西结合起来,

为中国服务。能与中国一起成长和发展,是我最大的心愿。选择,让我感觉痛苦

Xu Zonghan (American, brand consultant)

My life is a mixture of East and West, modernism and tradition. I feel bored when I stop working, but life seems to be such a fuss. Working in America is less interesting than in Shanghai. There, you just work for money. I’m Chinese and I want to do something for China, to combine the nice things of America and China. My biggest wish is to grow and develop with China. Choosing is difficult.

孟如顺 (上海籍 退休工人)

朱凤英 (上海籍 退休工人)

希望子女好,我们自己不要生病

Meng fîushun (from Shanghai, retired worker)

Zhu Fengying (from Shanghai, retired worker)

We hope that our children will be successful in their jobs and we will be healthy.

黄豆豆 (上海籍 舞蹈家)

我现在团里担任艺术总监、编导、主演,工作非常地繁忙。

平时连练功的时间都没有,只能边工作边练功,节省时间,一举二得。希望能出

国去进修现代舞的编导,在业务上再提高一步。要说痛苦,那就是我现在没有

正常人的生活。

Huang Dou Dou (from Shanghai, dancer)

I work as the art director and lead dancer for the troupe. I’m quite busy and even don’t have time to rehearse. I have to rehearse while working – two birds with one stone. I want time to go abroad for further studies and to improve my skills. I am sad that I can’t have a normal life.

高 鸣(吉林籍 无业)

我每天在家里思考一些人类精神层面上的问题,希望时光能够往回倒流,

我不知道社会是方的还是圆的。绘画和养花是我的二大爱好。通过绘画可以表达

生存状态感到还可以,每天能够按照自己的方式生活;广义地说,我没什么可以

说不满意的,妻子挣钱供养着我,而我整天干着不务实的事(苦笑)。我为自己

精神上不够完善,性格上较懒散,生活能力不太强而感到痛苦。

Gao Ming (from Jilin, unemployed)

Every day I think about philosophical questions. I want time to go backwards and I want to know whether this society is square or round. Painting and grow-ing flowers are my two hobbies. I express my thoughts, beliefs, and feelings through painting, while I can communicate with nature by growing flowers. In a narrow sense, I’m satisfied with my present life because I’m living in the way I want; in a broad sense, I have nothing to complain about. My wife works and supports the family and I’m just doing unpractical things all day long. My pains are my imperfection in spiritual life, my lazy character, and my weak viability.

李 游 (上海籍 公司职员)

我在一家外资公司工作。白天上班心理压力很大,精神上紧张,工作又忙。

下班回到家什么事都不想干,先把自己泡在浴缸里身心放松二小时,看一部碟片

享受一下。我还是一位业余的网络作家。

Li Kou (from Shanghai, corporate employee)

I work in a foreign company and have a lot of pressure. The only thing I want to do after work is to have a two-hour bath and then watch a DVD. In addition, I’m an amateur writer on the Internet.

谭锦盛 (上海籍 退休工人)

我现在寄宿在同事小杨家里,生活的很满意。我什么都不想了,就希望身体健康,

享受晚年。虽然儿子对我很好,但因为不住在一起,所以我感到孤单。

Tang Jinsheng (from Shanghai, retired worker)

I’m living at my colleague’s as a guest and I’m happy about my life. My son has been good to me, but I feel lonely because I don’t live with his family. Now I just want to have good health and a happy old age.

Qin Lei (from Hubei, hairdresser)

秦 磊 (湖北籍 发型师)

我的生活与幸福美满的人相比,还不如。但和不幸的人比较,就好多了。挣钱

固然重要,但还是要有人情味。不是什么钱都可以挣的,要有道。我最想躺在水边

听音乐,下象棋。生活中痛苦总是有的,这时我就独自去河边游走。时间长了,

自然也就过去了。

刘建敏 (广东籍 美发店学徒)

我的生活很简单,就是工作,玩。过日子吗,开心就好。想那么多有什么意思?

Qin Lei (from Hubei, hairdresser)

My life is worse than lucky people’s but better than unlucky people’s. Money is important, but there are things money can’t buy. I dream of lying down beside a river and listening to music or playing chess. I go to the river when I’m unhappy. Pain exists everywhere in life; we should learn to deal with it. Time is a good soother. Liu Jianmin (from Canton, hairdressing apprentice)

My life is simple and consists of just working and playing. Being happy is most important in life, and it’s useless to think about many things.

景茗 (上海籍 公务员)

我们的生活过得舒适,悠闲,

对目前的生活状况感到满意。我想学一门手艺,如木工或机械制作。因为我从小

就喜欢摆弄钟表,很开心。但生活中有许多无奈。

叶敬 (上海籍 英语翻译)

英语翻译是我的爱好,能将爱好变成我的职业我很开心。但自由职业开头接业务

很难,我希望多工作。我还想从事与动物有关的工作,比如:开动物园,水族馆

和宠物医院。遗憾的是没有时间。

Jing Ming (Shanghainese, Civil Servant)

We are satisfied with our present life, it’s nice and comfortable. I want to learn a skill, such as woodworking or mechanics. I like studying watches and clocks from childhood. I’m happy but many things are just hopeless. Ye Jing (Shanghainese, English Translater)

English translation has always been my hobby and I’m happy that i become a professional translator. It’s difficult to be a freelancer at the very beginning. I want to take up jobs that are related to animals, like working in a zoo, aquarium, or pet clinic. The only pity is that I don’t have time.

林路 (上海籍 大学副教授)

我工作比较紧张,忙不过来。业余时间几乎也都用在了工作上。

但我会自己调整,不把自己搞得太累。抽空看看电视里的体育新闻,足球比赛,

调剂放松一下身心。我喜欢过休闲放松的生活,有时间翻译国外的摄影理论,

研究摄影家和作品,撰文著书。现在时间和精力都不够用。钱也都花在买国外

摄影画册上了。愿家人平安。我没有痛苦,一直以来都比较顺利。

Lin Lu (from Shanghai, associate professor)

I spend most of my leisure time working. I know I shouldn’t work too much, and therefore I make time to watch sports news or football games to relax. I like to lead a comfortable and easy life and have tried to translate foreign photographic theories, study photographers and their works, and write books. Now I don’t have time and energy for all of this and I spend a lot on photography books. I hope my family is safe and sound. I don’t have difficulties; life has always been good to me.

Restratified Private Space

by Lei Ping

If a city has its own memory, we must search for it through the medium of past expérience. As Walter Benjamin reflects in his “A Berlin Chronicle,” “The ground is the medium in which dead cities lie interred. He who seeks to approach his own buried past must conduct himself like a man digging. Shanghai’s countless façades are like precious fragments or tor-sos, awaiting for urban observers such as Hu Yang, who witnesses the city’s changing temporal and spatial rhythms in order to locate and relocate the meaning of loss and historical irreversibility.

Hu Yang’s artistic and philosophical photographs portray more than five hundred families living in post-socialist Shanghai. Positioned in the hustle-bustle beat of the city, these pictures, both individu-ally and collectively, appreciate and capture the true essence and spirit of this city through the lens of its most private interiority – everyday dwelling space. Hu Yang is not only an art practitioner, but also a teller of stories about contemporary urban life. From the laid-off Shanghainese workers to the low-income floating peasant workers, from the carefree artists to the newly well-off native and foreign entrepreneurs, Hu Yang views disparate social spaces as images and relations that evoke reflection, from which he searches for his reality, reading and demystifying the languages of ordinary people from all walks of life in this post-socialist metropolis that was once known as the Paris of the Orient.

The cosmopolitan glamour of Shanghai offers an interesting contrast with its urban spatial configuration. Since Deng Xiaoping’s southern tour in 1992, Shanghai has been strategically repositioned as one of the economic backbones of China’s intensified reform in the era of post-socialist global capitalism. With its unique locality and social, historical, and political identity as an urban core, Shanghai has car-ried its mandate as an international treaty port since the Opium War and continues to play a strategic role as a global city. Some major policies have begun to redefine ordinary people’s everyday life and reconfigure their private dwelling space in this city, such as reprivatization of the economy, waves of consumer and real-estate frenzy, political relaxation of mobiliz-ing support for the central government, and rapidly intensified programs of technological, economic, and intellectual exchange with other countries in the context of globalization.

In this heavily loaded socio-political context, Hu Yang envisions the complexity of “Shanghai living” with his camera. One of the thought-provoking series on urban demolition presents the unidentified anxieties of local urbanites who are facing uncertain-ties regarding their living spaces during the relocation and displacement processes. A photograph fea-tures a retired Shanghainese couple (Sheng Chaozhen and Fan Jiujin) and their son who live in an extremely crowded room with their daily commute tools (bikes), miscellaneous cookware, and entertainment items (birdcages). Hu Yang’s ethnographic approach to this family results in the following narrative: “A real-estate developer saw our land and tried to persuade us to move. We have been locked in a dispute for more than two years, and life is very hard. We are surrounded by the builder’s trash and dust, as well as flies and mosquitoes. We hope the government will help us resolve this situation soon.” The family members’ facial expressions portray their astonishment, disappointment, and desperation about their living space: they are deeply confused by the effects of the demolition project, and they have no clue of who the ultimate “predator” is. In his photograph of another retired couple, Tan Hongzhang and Chen Lingmei, Hu Yang calls attention to a comparable situation: they live in a shikumen2 house and are awaiting for a forced relocation notice from the government. Their hopeless, agitated voices are heard through Hu Yang’s interview: “We’ve heard news about the government’s pulling down the house, but nothing has happened yet. Anyhow we won’t be able to afford an apartment downtown. Now we live with our elder son in this shikumen house; it’s small but the location is very convenient. Our greatest problem is the housing.” Between the legiti-mately propagated suburban dream and commer-cialized everyday life, there is a sense of distress and victimization intertwined with a not-yet-fulfilled promise of future progress and a better life.

The tremendous détermination of the new demands a ghostly demarcation from the old and a vigorous remake of the city’s private space.

Ever since the government made the decision to demolish Shanghai’s urban spaces, the city was bound to be dressed up as another surreal postmod-ern hyperspace to conjure up and compete with the project of modernization and globalization. The tremendous determination of the new demands a ghostly demarcation from the old and a vigorous remake of the city’s private spaces. Under the logic of deterritorialization and reterritorialization of global capital, the urban centre must give way to the global standards of profit and luxury. That is, people like these retired couples are expected to understand the call of postmodern global market economy and urban gentrification. Their jammed living space, as displayed in Hu Yang’s photographs, seems as over-crowded as yesterday’s living room, its “untimely” and “dislocated” nature an obstacle on the post-socialist expressway to becoming the science-fiction global capital.

Hence, restratified distinctions of social class are in the making along with the restratified interiority and exteriority of the post-socialist Shanghai. As both Deborah Davis and Nancy Chen state, the cities are the most visible and concentrated sites of this drastic and at times violent economic, social, and cultural transformation. In this context, Hu Yang ponders the internal tensions and contradictions of the post-socialist market economy, and finds new meanings by visualizing and documenting ordinary people’s everyday struggles and celebrations over their living space. The divergence between rich and poor, empowered and disempowered, converges in his representation of the urban. As viewers, we are hardly able to look away from photographs such as the one of a family (a hardworking couple from Shangdong with four children [too many by Chinese standards]) experiencing hardship, low income, and insufficient dwelling space; the one of a laid-off Shanghainese worker who takes “leisure naps” and decorates her room with supermarket fliers; and that of peasant workers/urban floaters who share bunk beds in a tiny room with dozens of others.

In contrast, Hu Yang critically and relentlessly juxtaposes a distinguished group of the newly rich. Their modern, lavish lifestyle and immaculately manicured and expansive private spaces seem to manifest to the world that they are completely content with life as it is. In the photograph of a Shanghainese general manager, Tang Zhenan, who is reading with his wife harmoniously in their Renaissance-style sun-flooded living room, Hu Yang’s camera enters a universally claimed utopian moment of upper-middle-class everyday life. And certainly, there is a golden room in some gated Shanghai mansion where wealth is nor-malized as everyday necessity. Here, Hu Yang attempts to create a visual shock with the symbolic and material capital through which the concealed property owner is ultimately identified and revealed. However, the intensified redistribution of social wealth and status in the post-socialist era of market reform that he portrays has already generated deep impacts and possibilities for people from different class spectra in Shanghai to renegotiate their socio-political positions.

In Hu Yang’s radical documentation of the visual, the social, the historical, and the political, his photographs in Shanghai Living uncover multiple layers of the most private and invisible with a critical eye. The mundane practicality and topography of interior urban space in Shanghai comes to a dialectical stand-still in the images that he has captured, from which the city is endowed with consciousness of reflection.

1 Walter Benjamin, “A Berlin Chronicle,” in Reflection: Essays, Aphorisms, Autobiographical Writings, trans. Edmund Jephcott, New York : Schocken Books, 1978, p. 25-26.

2 Shikumen means, liter-ally, “wooden door within a stone framework.”

Hu Yang specializes in documentary photography. A native of Shanghai, he gained visi-bility through an ambitious photographic project, Shanghai Living, produced in 2005, part of which was presented for the first time by the ShanghART Gallery the same year. He has since been invited to participate in numerous exhibitions outside of China, includ-ing the Netherlands (2006), Russia (2006), and the United States (2005). Recently, his work was in Reversed Images: Représentations of Shanghai and its Contemporary Ma-terial Culture, an exhibition organized by the Museum of Contemporary Photography in Chicago (2009). Hu Yang is represented by the ShanghART Gallery in Shanghai.

Lei Ping is a doctoral student in East Asian studies at New York University. Her major research interests are twenti-eth-century Shanghai cinema and literature, urban space theory, Chinese (post)modernity, and class, urban, and

cultural studies.