[Spring 2010]

by Gary Michael Dault

Olga Chagaoutdinova was born in the northern Russian town of Khabarovsk, which is about seven hundred kilometres from Vladivostok. She was twenty years old when Mikhail Gorbachev intro-duced perestroika; the sweeping “restructuring” of her country set her adrift, as she puts it, leaving her “unable to see what to do, or where to go.”

As a member of the first generation of post-com-munists, Chagaoutdinova quickly set about to give her life new definition. “I called myself a dinosaur,” she told me recently. “I had no future, and so, like many of my generation, I began to search for possible new lives.”

To that end, she married, had a child, and soon established a rather sophisticated advertising and publishing company in eastern Russia (“I was very poor, I was very rich, the pendulum always swinging to extremes, ninety degrees one way and then ninety degrees the other way”). After earning a degree in Russian language and world literature, in 1993, and a certificate for graduate work in “culturology” (she continues to doubt that there actually is such a word), in 1995, at the Republican Institute for Humanities at the State University, St. Petersburg, she came to Canada in 2000, finding her way first to Vancouver and the Emily Carr Institute of Art + Design. There, her work drew the attention of one of her teachers, photographer Roy Arden, whose supportive role in the shaping of her early career she continues happily to acknowledge. She then journeyed to Montreal, where, in 2005, she earned her MFA in photography from Concordia University.

My first acquaintance with Chagaoutdinova’s art came not through her work as a still photographer, but at a viewing, a few months ago, at Galerie Trois Points in Montreal, of two of her videos, Storm-ache and Stone-ache. Both are galvanizingly theatrical, disturbing, and unforgettable works, one being the opposite of the other. Storm-ache (the “wet” video) shows the artist sitting in a rather insubstantial little dress on a sea wall (in Cuba), her back to the onrush-ing, wind-lashed waves that inevitably come crash-ing over her. Because the rhythm of the great break-ers is irregular, Chagaoutdinova cannot adequately prepare herself for the next watery onslaught, which, when it hits, seems awesomely destructive, leaving her shaken, soaked, limp, and exhausted. The other video, Stone-ache (the “dry” video), shows the artist, in the same woefully ethereal and non-protective dress, repeatedly falling or rolling down what appears to be an enormous and fearsomely abrasive pile of gravel (somewhere in the Gatineau hills) -only to reappear again (thanks to quick, cruel editing) at the top, clearly condemned – like a feminist anti-Sisyphus – forever to roll down again.

I found it almost impossible, watching Storm-ache, not to think about the ninth of Walter Benjamin’s twenty-eight famous Theses on the Philosophy of His-tory. This thesis, the most familiar one, is concerned with Benjamin’s meditation on Paul Klee’s Angelus Novus and how the angel appears about to be swept along by a storm “blowing in from Paradise,” a storm that will propel him “into the future to which his back is turned… . This storm,” Benjamin continues, “is what we call progress.”

For the storm-ravished Chagaoutdinova, the new wave, the next wave (call it the breaking over her head of capitalism and its discontents), is just as oppressive as the ones that have come before. This sense of being propelled backward into the future -or perhaps only as far as the present – can be said to inform Chagaoutdinova’s exquisite still photographs as well as her videos.

The photographs, which were the result of Chagaoutdinova’s first trip back to Russia five years ago (a trip precipitated by her father’s having suffered a stroke) and a subsequent trip to Cuba, are mostly of interiors (there are some portraits as well). Parsed by and tinctured with the ideological and societal arc, erected during the past twenty years, from socialism to capitalism, the photographs that make up the tra-jectory of her project offer, as she has written in an artist’s statement, “visual evidence of a culture in transition.” Chagaoutdinova once remarked to me -rather paradoxically, I thought – that in the course of her first post-communist journeys, she missed “a sense of openness” in the people. “People are more careful now.” You’d have imagined the opposite to be the case.

The people are more careful now. Careful and, apparently, archivally given. Chagaoutdinova’s photographs, which respond delicately and yet search-ingly to this “care,” are about cultural suspension, about cultures-in-aspic. “The angel of history,” writes Svetlana Boym in her book The Future of Nos-talgia, “freezes in the precarious present, motionless in the crosswinds, embodying what Benjamin calls ‘a dialectic at a standstill.'”1

Each of Chagaoutdinova’s photographed interiors is an embodiment of what Boym calls someone’s “personal memory museum.”2 Her photographing of the homes of Russian and Cuban “internal exiles”3 constitutes a turning inside-out of what is most often the conventional desire of an émigré artist -the documenting of the lives of fellow emigrants. Chagaoutdinova was, by contrast, emigrating to her own home (or, in the case of the Cuban visits, to sites fragrant with auras and valences similar to what she had known in her own Soviet past).

And clearly, given the content of her photographs, there is only a porous boundary between collectivity and collecting. Speaking of Russian émigrés and their foreign apartments, Boym writes, “Their ways of making a home away from home reminded me of old-fashioned Soviet interiors, where each object had an aura of uniqueness – whether it was grand-mother’s miraculously preserved antique statuette or a seashell found on the beach of a memorable Black Sea resort in the summer of 1968.”4 The same conditions – that way of making a home within a home – appear to prevail in Russia and Cuba, as in, say, London or Paris.

Each of Chagaoutdinova’s photographed interiors is an embodiment of what Boym calls someone’s “personal memory museum.”

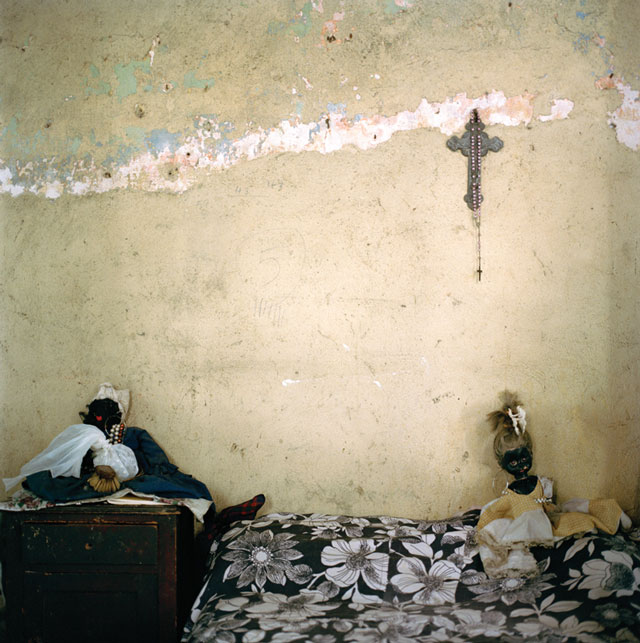

Chagaoutdinova’s interiors are full of tchotchkes: crosses on the wall, dolls on beds, a bear statuette and a portrait of Sisoev (from her hometown of Khabarovsk), and, in A Boy (taken in Cuba-Trinidad), a baroque table so laden with vases and attendant bits of kitsch that the boy in the title is almost entirely eclipsed, graphically speaking. There are also a great many scenic murals: vistas of escape, dream, and will-ing displacement. And chairs, tables, and beds – all anthropomorphized surrogates for absence.

“I am obviously searching for myself,” Chagaoutdinova says to me one day. I tell her about Svetlana Boym’s noting, in her The Future of Nostalgia, that nostalgia is to memory what kitsch is to art. “At first glance,” Boym writes, “nostalgia is a longing for a place, but actually it is a yearning for a different time”5 – the time of childhood, perhaps, or the slow-moving time within dreams. “That’s it exactly!” says Chagaoutinova, and I think she’s the one to know.

1 Svetlana Boym, The Future of Nostalgia (New York: Basic Books, 2001), p. 29.2 Ibid., p. 328.

3 Ibid., p. 330.

4 Ibid., p. 335.

5 Ibid., p. xv.

Olga Chagaoutdinova is a visual artist based in Montréal. Her work reflects her fascination with cultural codes whose exchanges construct personal identity, values, and collective and individual memories. Her solo exhibition at Trois Points Gallery, Montreal, earned her recognition by Canadian Art as one of the ten best graduate students in Canada. International exhibitions, awards, and residencies have since followed. Olga Chagaoutdinova is represented by Trois Points Gallery, Montreal. www.olgachagaoutdinova.com

Toronto writer, critic, and painter Gary Michael Dault is the author of ten books. His art review column appears each Saturday in The Globe & Mail.