[Winter 2011]

by Chuck Samuels

Chuck Samuels: More than one critic, including myself, has noted that the distinction between the autobiographical and critical aspects of your work is often blurred. Can you address how these two components manifest themselves in Before Photography ?

Chuck Samuels: Like much of my earlier work, Before Photography is primarily about my relationship with memory, photography, and cinema. As I began to work on this project, my daughter was in the midst of adolescence and the strains in our relationship sparked a reflection on my relationship with my own father and, more generally, on the ties and tensions between parent and child. This rumination provoked an epiphany: I realized that my father, a good amateur photographer, expressed his love for his family with his camera. And I suddenly understood why I became a photographer who frequently photographs himself. But why had my father taken up photography ?

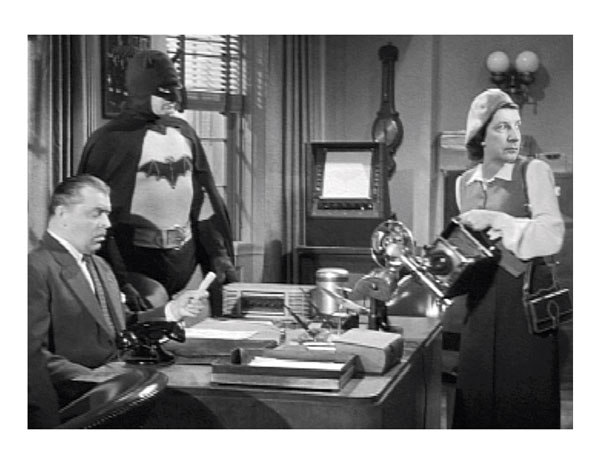

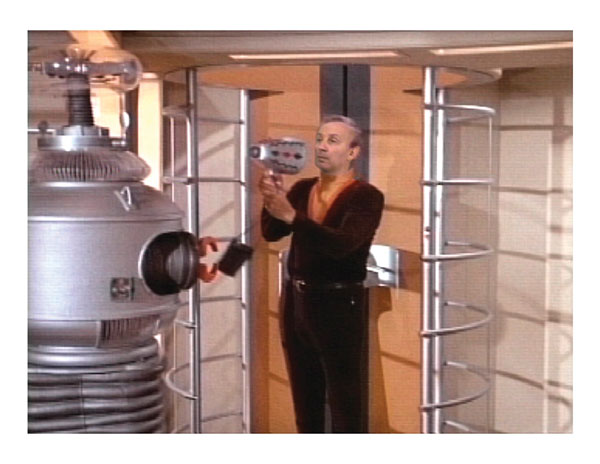

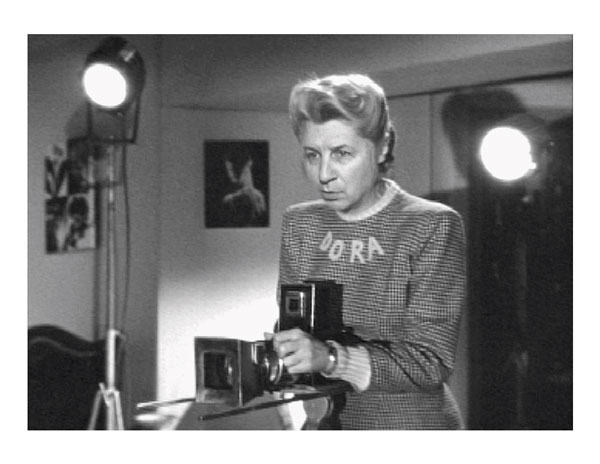

When I started working on Before Photography the project was meant to examine this particular question, but ultimately it became an exploration in which I quickly became hopelessly lost. I found myself wandering aimlessly among my own cinematic memories, the collective cinematic iconography of my father’s generation, and what I could only imagine to be my father’s memories. The project finally settled into a visual journey in the realm of the popular cinema and television of my father’s era (prior to the moment in 1967 when he introduced me to the practice of photography) in an attempt to unearth what it was about photography that may have seduced my father. It also inspired me to create the other elements that make up Before Photography.

CS: Yes, I’ve noticed that the presence of your father seems to haunt the entire project. Obviously this brings me back to the question of the autobiographical nature of the project.

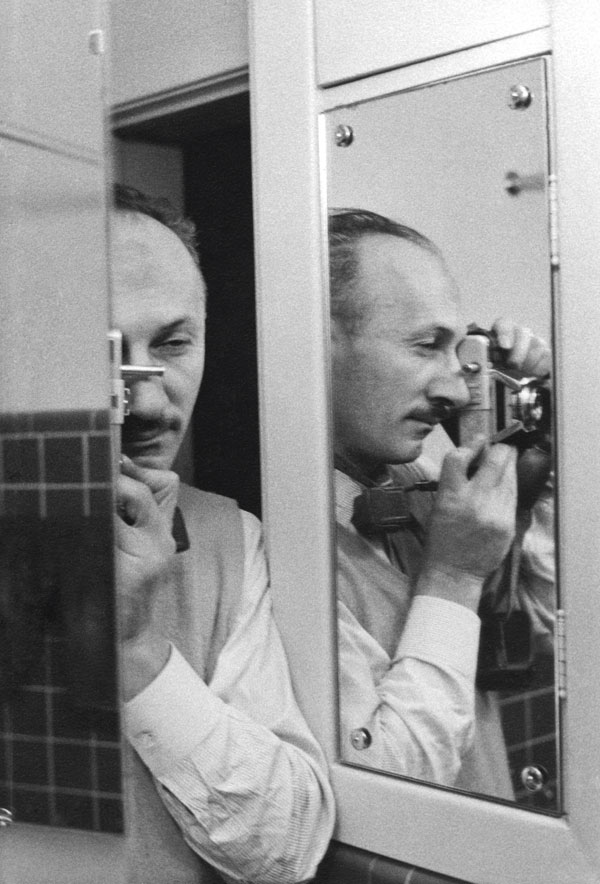

CS: Before I summarily dismiss that notion, let me first say this. Some of my most cherished childhood memories involve standing with the back of my head against my father’s belly looking through the viewfinder of his camera that hung from a brown leather strap from his neck. I can distinctly remember the musty animal smell issuing from the leather of the camera case, the autumn cold metal feel of the camera in my hands, and the irresistible allure of the shutter button. My father instructed me not to take any pictures, but I was unable to resist. I invariably pressed the shutter.

In 1967, during my induction into the practice of photography, my father gave me my first camera, a post-war Zeiss Super Ikonta, a wonderfully complex small camera with a large negative. I recall the leathery aroma emitted when the front of the camera was sprung open and the lens automatically slid down a rack, the bellows unfolding in hot pursuit. Using this camera, my father took a photograph of me just prior to handing it over, so the first shot on my first roll of film is this portrait of me. From the very beginning (if not before), my apprenticeship and practice of image making was linked to a fetishistic attachment to the camera.

But despite these nostalgic musings, I have to insist that Before Photography, like my previous work, is not based on a true story. In fact, insofar as it is relevant to my work, I could have just as easily invented everything I’ve just told you.

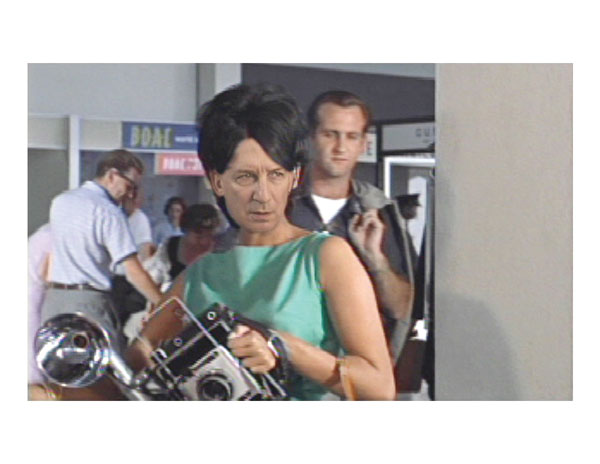

CS: It’s clear that the spectre of the camera can be felt in many, if not all, of your projects as an anchor to the self-referential aspect of your work. But never has the camera been more present than in Before Photography. In fact, it seems to be a character or characters in the project. Could the section Chuck Goes to the Movies, with its vast inventory of photographic paraphernalia and its play on the figure of the photographer, be considered the core of your exploration of the image ?

CS: In Chuck Goes to the Movies, I am the camera. I am the photographer. I am photography. And, of course, I am the subject. I am an actor who plays all those roles in a movie – in many movies, not all of them good. But to answer your question, no, it’s not the core but it is probably the most delirious, compelling, and accessible of the four sections that make up Before Photography. Chuck Goes to the Movies and Chuck’s Home Movies deal literally with my place in photography and cinema, while Chuck’s Family Photos and The Last Words on Photography draw links between my family, my introduction to photography, and the importance this discipline plays in my life. But there are also cross-references among all four components. For instance, the camera plays a significant role in each of the sections. The two video pieces share a kind of audio and visual cacophony; The Last Words on Photography echoes the impenetrable chaos of personal memories and their attempted reconstruction; Chuck’s Home Movies resonates with the overpowering common memory of cinema. And, of course, I appear in all the sections.

CS: Yes, I noticed that. You have used yourself as model in many of your projects and insinuated yourself into the work of other artists. How do you cope with the narcissistic connotations and the cult of personality that this self-representation and self-promotion may carry ?

CS: I’m not sure I like that question, particularly coming from you. How did you come up with a question like that ?

CS: It’s an essential line of inquiry, even if it makes you uncomfortable. But we can both take comfort in knowing that if one can accept that Zelig was not Woody Allen’s autobiography, it appears obvious that the act of photographing myself is to effectively turn the camera upon itself – to examine photography and, to a lesser extent, cinema, to see how it functions and how it doesn’t function. You could say that I use myself as stand-in or a sort of stunt-double for photography and cinema.

Since my first exhibition in 1980, I have been making self-referential works – or works that question the medium – and in many of these projects I have photographed (and filmed) myself to better shift the spectator’s gaze upon the very nature of photography and cinema. Using this approach, I have commented on the futility of the documentary impulse in The Mission of Photography… (1985), examined how viewers accept as normal certain photographic representations of the female nude in Before the Camera (1991), and meditated on how cinema presents the Other in Psychoanalysis (in collaboration with Bill Parsons, 1996).

CS: I see. If you are, as you claim, the incarnation of photography, then the period of time prior to you becoming a photographer – before 1967 – could be seen as “before photography.” Have I stumbled on the raison d’être of the title ?

CS: You’re very clever. Why don’t you try asking me a question that might trick me into admitting the fundamental autobiographical nature of the work that I have been adamantly denying ?

CS: Okay. What did you learn by producing Before Photography ?

CS: That I have much bigger ears than most Hollywood stars.

Chuck Samuels’s photographs have been exhibited, published, and collected extensively in Quebec, Canada, and abroad. His installation and video works have been presented in various venues, including several Canadian film and video festivals, and his photographs are in numerous collections in Canada, France, Belgium and the United States. Before Photography, his most recent photo-and-video installation, has been presented at Dazibao, centre de photographies actuelles in Montreal and VU, centre de diffusion et de production de la photographie in Québec. Chuck Samuels is director general of Le Mois de la photo à Montréal, and he lives and works in Montreal.

Chuck Samuels is a very occasional freelance critic with articles published in such Canadian contemporary arts magazines as MIX, Fuse, and Vanguard (co-written with Moira Egan). Samuels contributed a chapter to Women and Men: Interdisciplinary Readings on Gender, edited by Greta Hofmann-Nemiroff published by Fitzhenry-Whiteside in 1987.