[Spring/Summer 2011]

by Johanna Mizgala

It is nice to stare – particularly at beautiful people who in part make their living as the object of your gaze, each making a concerted effort to appear as though they might actually exist solely for the purpose of your continuing adoration. The very nature of fame relies upon the symbiotic needs of the adored idol and the adoring public. Recognition is a form of social currency, and our fascination with celebrity is insatiable. In order to keep the stardom machine running, we are offered glimpses, choreographed by press agents or stolen by paparazzi, into the lives of these extraordinarily fascinating creatures, as though voyeurism were somehow analogous to intimacy. In an age in which celebrities think of themselves as brands and thus market their very existence, image is everything, and thus images are paramount. Through advertising, pop culture, social media, reality television, and round-the-clock entertainment news, the more we see, the more we feel we know, and we can somehow identify with the stars and other mass-media icons. Integral to this consumer relationship is the sense that we are on a first-name basis; yet, ultimately, we are accomplices to our own delusion. Our affiliation amounts largely to a carefully constructed fantasy world, or, at the very least, a piece of theatre for the common people. For without an actual interpersonal interaction between us and them, this sense of association remains at the level of a beautifully glossy surface.

Within the context of celebrity culture and its diffusion by means of the photographic image, Martin Schoeller’s portrait series titled Close Up is arresting not only in terms of the monumental scale of the individual works, but, more importantly, because his photographs so clearly undercut the prevailing notion that celebrity portraits, or any portrait of a stranger for that matter, offer viewers a revelatory and intimate moment. Schoeller possesses a first-hand understanding of the power of personality: in addition to his art practice, he continues to be a much-sought-after photographer for magazine shoots and other commercial images. Thus, ironically, he is responsible for perpetuating some of the very cult imagery that his extensive portrait series succeeds in knocking so squarely on its ear.

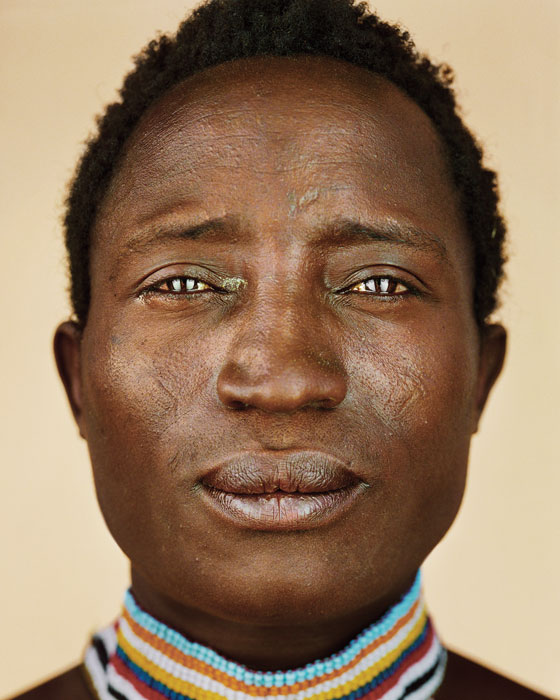

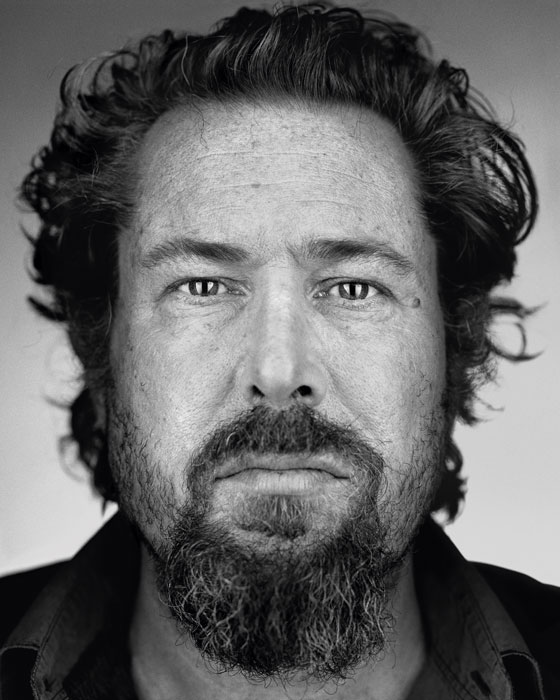

Schoeller began the series in 1998 and made a portrait per week for over seven years, subjecting some of the most recognizable faces of contemporary times, as well as private individuals, to the same taxonomic experiment of rendering every minute detail of the surface of their faces in gigantic proportions, as though their passport photo had been blown up to the size of a billboard. The portraits are exceptionally large, doubly so, because each picture plane squarely contains little but the head of the subject posed impassively, facing squarely forward, and looking directly into the camera lens. There are no superfluous details – neither in terms of the expected visual clues to indicate where the sitting took place nor in terms of any objects of personal significance to the sitters or accoutrements of their chosen arena of fame that might normally be included in a portrait as indications of their character. Schoeller deliberately banishes all such aspects of persona to outside the frame. The viewer is left with nothing but an endless expanse of face to pore over exhaustively. The experience should be the celebrity seeker’s nirvana, a never-ending place of the face, and yet looking into these colossal, spare, unretouched, and largely blank stares is akin to a double-take. Through Schoeller’s lens, the perennially identifiable star becomes a stranger, and the stranger becomes worthy of contemplation. We search each face endlessly for some outward traces of the familiar, only to be confronted with blankness, as though the subjects were experiencing a moment of amnesia regarding their own fame. In this void, the portrait sitters just aren’t what we expect, even though we might be seeing them in a decidedly more intimate and certainly more vulnerable state than hitherto experienced. This moment of being so very exposed to the other’s gaze has the opposite effect than might be anticipated – we don’t know them any better as a result of being literally so close to their faces that we see them as though looking at our own features in the mirror. For all the great stretch of visual terrain that we are given for scrutiny, even though the sitters are at the mercy of our gaze, they remain impenetrable to us. As such, the portraits in Close Up speak to the unrequited nature of celebrity fascination: when offered an opportunity to know the individual stripped so completely bare, the experience in fact removes the aura that made being close to them so desirable in the first place. They are present and yet utterly absent in a single expansive field of vision.

When offered an opportunity to know the individual stripped so completely bare, the experience in fact removes the aura that made being close to them so desirable in the first place.

In sharp contrast to the portraits in his Close Up series, in which all details other than the subject’s face are deemed extraneous, the portraits in Schoeller’s Female Bodybuilders series represent a modern take on the classic three-quarter pose, with each woman set against a blank white background. In this new series, Schoeller allows some traces of individuality for the viewer’s consideration, specifically through the highly personalized posing bikinis that each woman wears, as well as through her own jewellery and makeup. Ultimately, here too each stance is merely an echo of the previous image, and the portraits become less about the subject’s individuality and more about the exploration of a particular type of person. In this instance, Schoeller proposes a look into a closed-off world that is familiar only to the initiated few and thereby challenges notions of femininity and concepts of beauty.

Without more to consider than the highly muscular bodies that define each woman as a participant in this arena of competition, the portrait subjects appear all the more removed from the everyday world. More-over, competitive bodybuilding is an endeavour that requires not only an enormous effort in terms of physical endurance, but also an endless commitment to participation in a circuit of presentation of the body for the purposes of being judged. Competitors must perform a series of carefully choreographed poses to underscore their physical prowess and muscle development based upon rigidly defined standards. In Schoeller’s portraits, as their bodies are not shown in the flexed motion stances of competition, but in-stead appear at rest, the images present some women seeming slightly ill at ease and others somewhat defiant of the preconceived expectations that they must face from within and without their chosen vocation. There is a certain measure of trust implicit be-tween subject and photographer, but it does not seem to have come easily. There is beauty here, but also strangeness, very much in the way that celebrities appear to be in the world but not necessarily of it. They stand apart as objects of contemplation, like statues or mannequins. Both portrait series are unsettling precisely because they challenge the viewer with a return of the gaze. They stare back at us.

In creating such rigid parameters within which to explore the distinctiveness and individuality of the human face by way of multiple takes through the same objective point of view, Schoeller acknowledges a debt to the systematic program of photography of Bernd and Hilla Becher, as well as to the portraits of Thomas Ruff and also, perhaps, Rineke Dijkstra. Likewise, his interactions with celebrities call into question his own relationship as a photographer with the cult of personality and with the ways in which commercial images feed the need for attraction and the desire for adulation. Without this relationship, there would be no celebrity, no need for a way to bring together people who have been separated by an artificial construction. Ultimately, by rendering everyone a subject worthy of the same detached but exhaustive scrutiny, Schoeller proposes that the extraordinary can be rendered ordinary through repetition but that, nonetheless, the act of looking retains a measure of surprise, drawing the viewer in deeper than just a cursory glance to reflect upon desires that cannot be satisfied. We never truly tire of staring at people; instead, we just find new subjects to put into the spotlight.

Growing up in Germany, Martin Schoeller was deeply influenced by the work of August Sander and Bernd and Hilla Becher. He worked as an assistant to Annie Leibovitz from 1993 to 1996 and joined Richard Avedon at The New Yorker in 1999, where he continues to work while also shooting for other publications and advertising campaigns. His portraits are included in the permanent collection of the National Portrait Gallery in Washington, DC. He is represented by Hasted Kraeutler, Ace Gallery, and Camerawork. Martin Schoeller lives and works in New York. www.martinschoeller.com

Johanna Mizgala is a freelance curator, critic, and educator. Her doctoral dissertation addresses the subject’s sense of humour in early photographic portraits, the collaborative nature of the portrait sitting, and how free-spirited examples of transgression transcend distinctions of race, class and gender.