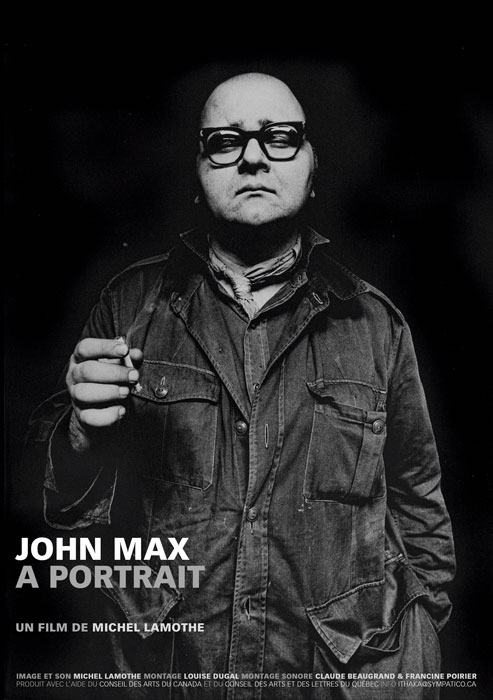

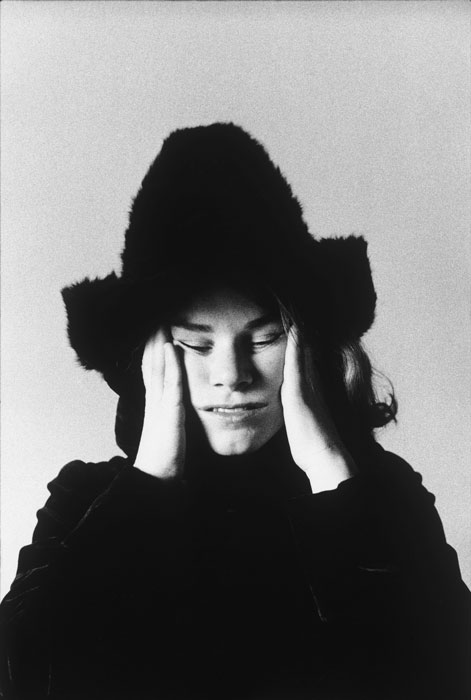

The Montreal photographer John Max died last May, just after the release of the film John Max, a portrait. This fascinating documentary was directed by his friend, filmmaker and photographer Michel Lamothe, who attempted to capture the paradoxes of an artist obsessed with the search for infinity. Here, we are publishing the very sensitive commentary that the artist and writer Charles Guilbert penned about the film. We are also taking advantage of this opportunity to pay tribute to John Max by showing some of the 178 images that comprise the series Open Passport, his most accomplished work, produced in 1972. He received the recognition of his peers for this work, although today the public is totally unaware of him. Lamothe’s film, and the exhibitions that will be devoted to his work in the coming years, will certainly help to redress this gap.

by Charles Guilbert

In John Max, a portrait, Michel Lamothe proves that an attentive gaze trained on the other may be transmuted into a deep meditation. To create this work, which is as fluid as a fiction film, Lamothe followed the photographer John Max for three years (from 2000 to 2003), accumulating 40 hours of footage – film that he spent months pruning and then editing, in collaboration with Louise Dugal.

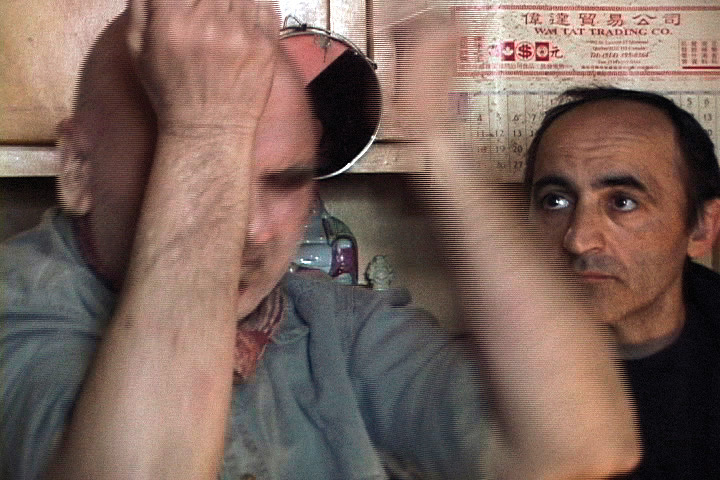

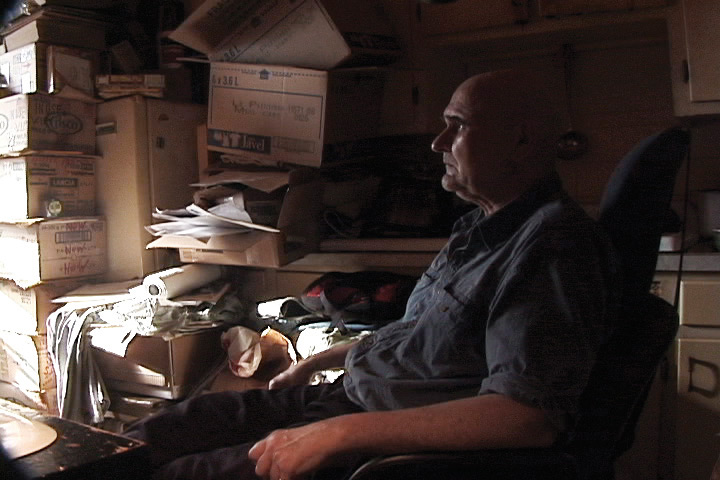

The film starts like a relatively classic portrait. We see John Max in profile, compulsively rolling cigarettes and talking about his earliest childhood memory (an intense quarrel between his Ukrainian parents), then his beginnings as a photographer (influenced by Cartier-Bresson’s The Decisive Moment). Lamothe’s footage is raw (shot in full-aperture mini-DV video) and the shooting angles are often tight. We quickly find out why: there is very little free space in Max’s apartment, which is crowded with boxes, books, and objects, and light barely filters in from the outside. But the filmmaker soon finds his footing, and the sensation of constriction becomes one of fecund intimacy.

In the first half of the film, Lamothe reviews Max’s art career. We see previously unpublished street photographs from the 1950s that reveal a Montreal both poor and dynamic.In John Max, a portrait, Michel Lamothe proves that an attentive gaze trained on the other may be transmuted into a deep meditation. To create this work, which is as fluid as a fiction film, Lamothe followed the photographer John Max for three years (from 2000 to 2003), accumulating forty hours of footage – film that he spent months pruning and then editing, in collaboration with Louise Dugal. The film starts like a relatively classic portrait. We see John Max in profile, compulsively rolling cigarettes and talking about his ear-liest childhood memory (an intense quarrel between his Ukrainian parents), then his beginnings as a photographer (influenced by Cartier-Bresson’s The Decisive Moment). Lamothe’s footage is raw (shot in full-aperture mini-dv video) and the shooting angles are often tight. We quickly find out why: there is very little free space in Max’s apartment, which is crowded with boxes, books, and objects, and light barely filters in from the outside. But the filmmaker soon finds his footing, and the sensation of constriction becomes one of fecund intimacy.

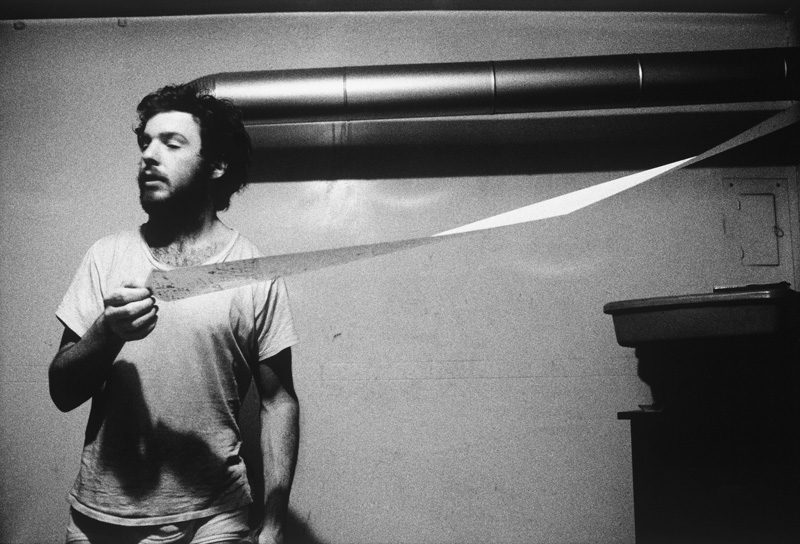

In the first half of the film, Lamothe reviews Max’s art career. We see previously unpublished street photographs from the 1950s that reveal a Montreal both poor and dynamic. Then there is a long sequence shot at the 1967 Paris Biennale, in which Max’s multiple head-shot portraits seem to give viewers direct access to the people portrayed. “I photograph what’s inside,” says Max. After that comes the most complete exhibition, Open Passport (1972), comprising about 160 photographs, for which Max innovated by appropriating the portrait form (most of the pieces were photographs of friends, with unstable images and powerful black areas) and making unusual presentation choices (hanging designed to draw viewers into the huge Photo Gallery in Ottawa; intuitive association of images; deployment of non-traditional narration; unframed prints in a large format for the time). The film, skilfully constructed, intermingles this immersion in Max’s work with interviews with people who talk about Max as a friend, artist, or teacher. In these fully frank and often tense – no doubt because the interested party is in the room – scenes, a complex portrait takes shape. We see Max with a neighbour, Cécile, who is unable to write because her medication is making her groggy; he suggests that she go back to her psychiatrist, as she is depressed about her overwhelming feeling of torpor and inability to act. Later, a friend breathlessly, and with frequent interruptions by his overexcited daughter, tells about a portrait that Max made of him when he was in a complete psychotic break and complains about Max’s sometimes-excessive calls for help. A former student describes the stormy climate of Max’s anti-conformist classes, as he tried to show how to convert his energy into photographic prints. In an apologetic sequence, Lorraine Monk, former director of the nfb’s Photography Service, says that she recognized John Max as a unique photographer, even a genius; in the most provocative scene, Leo Rosshandler declares that we should no longer pay attention to Max’s work because Max himself abandoned it after a four-year stay in Japan, from which he returned obsessed with spirituality and the belief that wishes make things come true. Max reacts strongly to Rosshandler’s criticisms, but we heard him admit, earlier, that he had lost several hundred photographs because he had put off developing them, that there were thousands for which he had not yet made contact sheets, and that he had several hundred contact sheets that he had not yet looked at. His excuses are that he does not have enough space and that his darkroom is too cluttered to work in.

The strength of the film is that Lamothe keeps this gripping story at the confluence of art and life… We understand that valuable images will never be revealed because Max simply cannot face the idea of making choices, and that all of his work is threatened with oblivion.

In fact, Max’s entire apartment is crumbling under the weight of the objects that he has collected here and there, with little regard for their value. The drama that has been simmering now comes to a boil, as threats of eviction become more and more serious. A visit by a city inspector reveals the scope of the disorder, including the lack of a heating system. Then come the real-estate agents, who brutally photograph everything. The film takes a new turn: it becomes a battle, in which Max sees the filmmaker as protector. He calls upon friends, including Gabor Szilasi, to provide reinforcements, and they get together to help him. Some try to convince him to get rid of the clutter, but in vain. All that Max wants to do is come up with delaying tactics. The tension mounts constantly.

The strength of the film is that Lamothe keeps this gripping story at the confluence of art and life. We cannot fail to recognize, though obliquely, that the frantic collecting to which Max succumbs – an activity that seeks, to paraphrase Raymonde April, to “embrace everything” – is, above all, a reflection on photography. It is also a reflection on time, the stretch of time between the taking of the picture and the creation of the artwork into which it is dangerous to sink. We understand that valuable images will never be revealed because Max simply cannot face the idea of making choices, and that all of his work is threatened with oblivion. The theme of imbalance is omnipresent, as both an aesthetic value and an indication of psychological fragility. We see Max’s irresistible attraction to instability in Open Passport, for example, a project in which duality is significant. Max designed the show as both a portrayal of human liberation and a diary of his inner life. The desire to be “without birthplace, without country, without borders” and the fact of being deeply rooted in an apartment on Rosemont Boulevard give rise to a dichotomy that is at the core of Lamothe’s film.

Toward the end of the film, freedom as a subject reaches a paroxysmal point. John Max is besieged by aggressive landlords impatient to dislodge him from this place that is his cocoon. Prevented from living his marginal life, he feels trapped by laws and general incomprehension. We are indignant with Max, but we also sense, in his complete refusal to see a future for himself and in the madness that is overtaking him, an intense fear of the outdoors.

Max has lived almost all his life in the house from which he is being banished. After his parents broke up, they continued to live there, taking one floor each. Once they died, the artist and his brother stayed there, also separated by a misunderstanding that Max describes as “a tragedy.” Subtly, the film weaves connections among this family dysfunction, Max’s fate, and his artwork. A film by a photographer on a photographer, John Max, a portrait is a disturbing work that brings together, with a rare density and coherence, the qualities of a portrait, a story, and an essay.

Translated by Käthe Roth

Charles Guilbert has a master’s degree in literary studies. A multidisciplinary artist, he writes, draws, sings, and makes videos.