[Winter 2012]

by Alice Ming Wai Jim

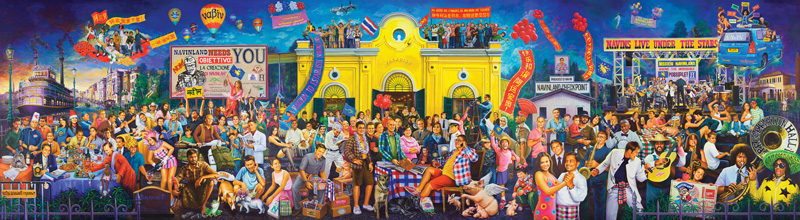

“Navinland needs YOU,” according to the s.w.a.g. (souvenirs, wearables, and gifts) cum recruitment material of Thai artist of Indian descent Navin Rawanchaikul’s latest staging of his fledgling non-nation. Set up in a bar and restaurant at the entrance to the Giardini, where the permanent national pavilions of the Venice Biennale have been since 1885, Paradiso di Navin: A Mission to Establish Navinland is a parody as astute as it is amusing of this year’s theme of ILLUMInations. With a record-breaking eighty-nine participating countries this year (up from seventy-seven in 2009), it’s not a bad entry for a biennale incessantly wrestling (as others since it) with the anachronism and future of national representation. At the U.S. pavilion inside the Giardini, Track and Field (2011), Puerto Rican–based Guillermo Calzadilla and Jennifer Allora’s overturned sixty-ton military tank repurposed into a treadmill powered by American track athletes, churns noisily. Clearly, competitive patriotism at the art world’s Olympics can be tongue-in-cheek, light fare, or high-impact; nevertheless, it is very seriously present.

Navin’s “nation-building” is Thailand’s contribution this year; this is the fifth time that the country is participating, although there is no Thai pavilion. In fact, few Asian countries have permanent pavilions in the Giardini. With the exception of Japan (since 1956) and Korea (since 1985), Asian countries began participating within the last decade or so, and most have spaces in palazzos, churches, galleries, and warehouses in various locations or within the sprawling Arsenale. Inaugural exhibitions by Asian countries this year include India, Bangladesh, and Saudi Arabia, whereas the United Arab Emirates presented “Second Time Around.”

In the India Pavilion, Kerala-born Gigi Scaria’s Elevator from the Subcontinent lets visitors in and out of a real elevator to visually access New Delhi’s different social layers (the urban scenes of busy streets and underground parking lots are backlit projections inside the elevator). The Benjamin-inspired illuminations theme notwithstanding, the media installation literally takes up the paternalistic “North-South” unidirectional flow so invested by the Euro- and American-centric art empire’s conception of how the South appears.1 According to the artistic director of the 2011 Biennale, Bice Curiger, its theme, as expressed in the catalogue, “seeks to emphasize the intuitive insight fostered by an encounter with art and its ability to sharpen the tools of perception.”

A number of exhibitions interpreted the biennale theme in metaphysical terms, showcasing Asian philosophy and aspects of the spiritual and sensual, the traditional and immaterial, as well as futuristic portents. Despite their focus on seemingly different kinds of meridians, respective national identifications remained intact, with some offerings more self-reflexive than others. Touting a nationalistic “flavour” (or “fragrance” – both words are conveyed by the same Chinese character), the China pavilion exhibition “Pervasions” featured five “safe” olfactory installations associated with Chinese traditions: tea (“clouds” by Cai Zhisong), lotus (by Pan Gongkai, rendered with traditional ink-painting technique as part of a semi-immersive media installation projecting the English translation of his essay “On the Border of Western Modern Art” falling letter by letter, like snow), liquor, or baiju (by Liang Yuanwei), medicinal herbs and spices (in ceramic pots, by Yang Maoyuan), and incense (atomized as a pungent fog pervading the entire pavilion and spreading out to the lawn, by Yuan Gong).2

The collateral event “Cracked Culture? The Quest for Identity in Contemporary Chinese Art” chastised “poorly informed foreign curators” and pugnaciously pressed for a distinctly national aesthetic or artistic practice – despite the diverse (though somewhat tepid) range that the event spread over two venues, not to mention the presence of decidedly post-national, if not post-media, exhibitions in this year’s biennale displaying the contrary.3 As it was, the necessarily political question concerning Chinese artists outside of biennale statism, “Where is Ai Weiwei?,” was more expediently visually posed by the in-the-know throngs around Venice sporting red “Free Ai Weiwei” canvas bags and by related activity in the Twittersphere.4

Dullness, the nature of biennales, the pursuit of a unifying regional aesthetic – in this case pan-Asian – under the sway of the familiar artificial east-west dichotomy, extended to another major two-venue Asian collateral exhibition, the massive “Future Pass: Asia to the World,” which featured 106 established and emerging artists from over fifteen countries, with most from China, Taiwan, Japan and South Korea. Curated “from an Asian perspective” by Victoria Lu, Renzo di Renzo, and Felix Schöber, “Future Pass” was organized around five dichotomous pairs: East/West, Past/Future, Yin/Yang, Universal/Individual and Virtual/Real, although these dichotomies were often lost due to the sheer number of works to peruse.

The majority of the works were in the style of what Lu describes as “the Animamix aesthetic,” a combination of styles from animation and comics that is not only “an artistic ‘nation’ that transcends national boundaries, but also a new artistic universe centered in Asia” – “a new aesthetic paradigm currently proliferating from Asia to the rest of the world.”5 teleco-soup, the not-unrelated immersive multimedia environment by Tabaimo at the Japan Pavilion in the Giardini, in part sought to challenge the view of Japanese animation as an example of the Galapagos syndrome. At the Korean Pavilion, Lee Yongbaek displays two “Animamix” moulded-sculpture Pietàs: in the first, the two figures (Pietà: Self-hatred) are iconic K1 fighters tussling to the death, whereas in the second (Pietà: Self-death), the figures are in the more commonly recognized pose in Christian art of the Virgin Mary cradling the dead body of Jesus.

Attributions of regional aesthetics, such as cute culture and cosplay, as increasingly globalized practices are debatably no less essentializing of cultures than is attempting to identify a national art proper. These exchanges do, however, propose a crucial forum to think through emerging global art histories – art history itself being a product of Enlightenment thought to which illuminations also makes a gesture.

Global comparative art histories came together most successfully in the expertly curated and well-conceived Singapore and Taiwan pavilions. Singaporean Ho Tzu Nyen’s The Cloud of Unknowing, accompanied by an equally impressive catalogue, takes its title from a fourteenth-century medieval primer for aspiring monks, although the cloud in Nyen’s video is less concerned with ecclesiastical instruction for prayer than with the ways in which clouds as polysemic sign have been represented in art and art history. Giving a liberal visual interpretation of works from Baroque classics by Caravaggio and Bernini to the Chinese landscapes of Mi Fu and Wen Zhengming, all in “the service of clouds” (after John Ruskin), the video’s eight sections are set in the decrepit units of a low-income public housing estate in Singapore that is slated to be decommissioned, but it is clear that the film’s real protagonist is the cloud, which permeates not only the screen space but the literal exhibition environment. According to curator June Yap, “Clouds, that reflect our projected imaginations, in representation become ‘notations’ of feeling and sensation . . . intensified in Ho’s installation through the use of audio and smoke.”6

As both medium and site, sound was the big hit in Taiwan’s offering at this year’s Biennale, complete with a Sound Library/Bar. The projects by prominent and emerging sound artists Hong-Kai Wang (Music While We Work, video and sound recordings of life experiences at a hundred-year old sugar factory), Su Yu-Hsien (Sounds of Silence, albums by Indonesian boatmen, a garbage picker aka Plastic Man, and a homeless man), and event artists Fujui Wang, Chi-Wei Lin, and DJ @llen (Taiwan’s godfather of Taiwanese electronica), filled the Palazzo delle Prigioni with the sounds of social movements and sound production since the lifting of martial law in Taiwan in 1987. The aural equivalent of Animamix? Who knows. But such exquisite transnational moments, in the end, are what compel us to partake in biennale culture.

2 The presence of Chinese artists since 1993 has been increasingly exceptionally strong, with both the establishment of China’s own pavilion in the Arsenale area since 2007 and its international stars well integrated into the Biennale’s group exhibitions and shown in private exhibitions in the city, such as the François Pinault collection at the Palazzo Grassi.

3 Quite the unfortunate title, which my partner swears up and down is a mistranslation of “fragmented culture,” in which case the event could be seen to doubly refer to illuminations as artistic director Curiger intended: “. . . the true creative overcoming of religious illumination certainly does not lie in narcotics. It resides in a profane illumination, a materialistic, anthropological inspiration to which hashish, opium or whatever else can give a preliminary lesson. (But a dangerous one . . .)” Walter Benjamin, “Surrealism: The Last Snapshot of the European Intelligentsia” (1929); emphasis in original.

4 Ai Weiwei, the Beijing-based artist, architect, and social commentator, was detained by the Chinese government on 22 April and released on 22 June 2011. The question is also raised in the second essay of the official Venice Biennale catalogue, an essay that, except for its title, bears no mention of Ai Weiwei. See Giovanni Carmine, “Where is Ai Weiwei?” illuminations, exh. cat. (Venice: Marsilio Editori; Fondazione Le Biennale di Venezia, 2011), 58–63.

5 “Future Pass – From Asia to the World, Le Biennale di Venezia,” 54. Esposizione internazionale d’Arte, Eventi collaterali, press release, May 2011.

6 June Yap, “Adrift on The Cloud of Unknowing,” in Ho Tzu Nyen: The Cloud of Unknowing, ed. June Yap, exh. cat., Singapore Pavilion, 54th Venice Biennale (Singapore: National Arts Council, 2011), 8.

Alice Ming Wai Jim is an associate professor of contemporary art at Concordia University. Her current research concerns include contemporary Asian art and biennale cultures.