[Printemps/été 2012]

by Érika Nimis

A number of events (exhibitions, publications, and awards) have recently highlighted the growing success of South African photography on the international contemporary scene. Since the abolition of apartheid, and then the election of Nelson Mandela as president of the country in 1994, South Africa has become the spearhead of contemporary African photography, reinforced by a long and rich history that begins with the invention of photography itself, imported to Cape Town in the 1840s.1 Very early branded with separation and segregation, dominated by the white minority, South African photography rediscovered all its colours when apartheid ended in the late twentieth century and a cultural policy was instituted in favour of reconciliation among all communities. This policy generated a form of “renaissance” that was to support the creation of training facilities, including the famous Market Photo Workshop in Johannesburg, and the burgeoning of exhibition centres, among them such internationally known galleries as Stevenson, Goodman, and Momo. Johannesburg and Cape Town gradually emerged as consequential art capitals hosting large-scale events (the Johannesburg biennales in 1995 and 1997, CAPE in the 2000s, and more recently, in Cape Town, the Bonani Africa Festival devoted to photography), providing a breeding ground for artists, including photographers, with free ideas and no clichés, who took sustenance from the new diversity of the “rainbow nation” and fought in their way to bring it respect.

Today, South African photography is metamorphosing into a mode of expression directly related to performance: many artists in the young generation… such as Athi-Patra Ruga, Zanele Muholi, and Nontsikelelo Veleko, use it to record the highlights of their performances, also imbued with Queer philosophy.

South Africa became a European colony in the eighteenth century, under the British, and then a republic in 1961, at the same time as the apartheid policy (instituted in 1948 to maintain the white minority in power) was strengthened. The ensuing decades saw discrimination against the black majority intensify, with bans on free travel, lack of access to education and the media, and other restrictions. The response by intellectuals and artists was not long in coming. In the forefront of the fight against apartheid were photojournalists who developed a highly engaged documentary style. In the 1950s, led by Jürg Schadeberg, the magazine Drum thumbed its nose at apartheid propaganda. But the laws quickly became more and more repressive, making photojournalism a dangerous activity and driving a good number of photographers underground or into exile. The 1980s saw a revival of activist photography through collectives such as Afrapix, whose vocation was to reveal to the whole world the terrible injustices of the apartheid system. This vision of South African photography as engaged, essentially documentary, and in black and white (simply because it was more accessible than colour) made a lasting impression.

Santu Mofokeng’s career is emblematic of the transition that the South African photography scene underwent in the 1980s and 1990s. Mofokeng had started as a neighbourhood photographer, covering festivals, baptisms, and marriages. Under apartheid, he didn’t have an opportunity to pursue an education and had to be content with an assistant’s position in the laboratories of various newspapers.

In 1985, with the support of David Goldblatt, a monument of South African photography, he joined the Afrapix collective (1982–91) and began to work freelance, but he had to stop after two years and return to the Townships, for safety reasons. Nevertheless, he didn’t abandon his documentary photography practice, although he felt that the engaged documentary photography of the 1980s, which was focused on denouncing the violence of apartheid, did not always allow photographers to express their full potential. In the early 1990s, the fall of apartheid made it possible for photographers to turn from activism toward personal projects. For Mofokeng, a long quest for identity began, embodied in his exemplary research on pre-apartheid family photography. In The Black Photo Album, 1890s–1950s, he explored portraits, taken before the institutionalization of apartheid, that he had collected from black families. He felt that the past must be examined in order to face the present. Around 1994, in the wake of the first democratic presidential elections, he travelled his country from end to end, finally free, to answer the question Who am I?

In 2011, part of the answer to this question was offered in the beautiful retrospective devoted to Mofokeng’s work at two European institutions, Jeu de paume in Paris and the Kunsthalle in Berne. With Chasing Shadows: Thirty Years of Photographic Essays, Corinne Diserens, the exhibition curator, brings a new and enlightening comprehension to this photographer’s body of work, traversed by South African history.

Now exhibited in all major institutions (such as the Victoria and Albert Museum in London, in 2011), South African photography has found a place in most private contemporary photography collections. Among the most important of these collections is that of Artur Walther, a German businessman from Burlafingen, near Ulm, in southern Germany. Walter has used his great wealth to create a vision that attempts to disrupt the clichés of 1960s African photography, which was limited to studio portraits, as seen in the work of Malian photographers Seydou Keita and Malick Sidibé. Among the South African artists in Walther’s collection, which also includes video art, are such major figures as Candice Breitz, David Goldblatt, Pieter Hugo, Zwelethu Mthethwa, Zanele Muholi, Jo Ractliffe, Mikhael Subotzky and Guy Tillim.How can Walther’s attraction to South African photography be explained? In 2005, he surrounded himself with renowned curators, including Okwui Enwezor (Snap Judgments: New Positions in Contemporary African Photography, presented at the National Gallery of Canada in 2007), to undertake a strategic “Africanization” of his collection. The collection’s inaugural group exhibition, Events of the Self: Portraiture and Social Identity (2010–11) offered an intermingling of the visions of African and German photographers, showing, for example, the possible connections between Seydou Keita and August Sander. The result left no viewer unmoved.

In spring 2011, the Walther Foundation opened a gallery in the Chelsea neighbourhood of New York, the Walther Collection Project Space. In a master stroke, the gallery’s first exhibition was devoted to recent work by South African photographer Jo Ractliffe, who is of the same generation as Santu Mofokeng. This series, As Terras do Fim do Mundo (The Lands at the End of the World) (2009–10), presented, with the clarity of an almost topographic gaze, black-and-white photographs of abandoned, desert-like landscapes that bore the traces of the thirty-year civil war in South Africa’s neighbour Angola – a war that was supported by the South African apartheid regime. Human beings are quite insignificant in the face of this void, this desolation, this silence, faced with these battered stretches that still bear the stigmata of the violent battle.

In another master stroke for South African photography, Mikhael Subotzky, a young photographer working for the Magnum agency, won the Prix Découverte at the 2011 Rencontres photographiques d’Arles, also with the support of Walther. The work for which Subotzky received the award, Ponte City, offers an almost encyclopedic portrait of the tallest apartment building in Africa, in downtown Johannesburg, which saw its population change (from white to black) when apartheid ended.2 This urban reality of post-apartheid South Africa was also covered by Guy Tillim, another major figure in South African photography, in his series Jo’burg (2004). Tillim, born in Johannesburg, became a photographer in the 1980s, at the same time as he became aware of the inequalities engendered by the apartheid system. Over the years, he, like Mofokeng and Ractliffe, created a powerful and personal body of documentary work, which has been widely exhibited, published, and awarded.

In 2011, his Avenue Patrice Lumumba (2007–08) was presented at the Design Exchange in Toronto during the contact festival.3 Jodi Bieber, another internationally renowned South African photographer, won the 2011 World Press Award for a shocking image published on the cover of Time Magazine: a serenely beautiful young Afghan woman, her features deformed by a mutilation inflicted by her father-in-law after she attempted to flee her abusive husband. This now extremely famous portrait refers to another series in which Bieber explores the generally accepted idea of beauty. Real Beauty (2009) is a gallery of portraits of South African women of all ages posing in their best undergarments. The photographer, playing on the tradition of the studio portrait, paid close attention to the décor and details of each pose. The reality of imperfect – normal – bodies was not compromised. There is no retouching; the subjects’ gazes are direct, totally trusting a camera that is on their side.

Today, South African photography is metamorphosing into a mode of expression directly related to performance: many artists in the young generation… such as Athi-Patra Ruga, Zanele Muholi, and Nontsikelelo Veleko, use it to record the highlights of their performances, also imbued with Queer philosophy. In a 2001 essay, William J. Spurlin wrote, “‘Queer’ identities and cultural practices in the ‘new’ South Africa are not merely forms of self-assertion and self-expression as they often are in the West, but are explicitly shaped by the resistance to fixed identities and fixed notions of culture previously imposed by the system of apartheid.”4

Zanele Muholi, a prolific artist trained at the Market Photo Workshop, became a photographer through activism, convinced that the perception of lgbts in South Africa will change if they are made more visible. Muholi photographs lesbians, alone or in couples, in private moments: a unique body of work, discreet yet strong, that has earned her a number of awards abroad, but has also drawn fire from the black establishment in a South African society in which lgbt people are not well tolerated. Like Bieber, Muholi uses the conventions of the traditional portrait to disrupt viewers’ generally accepted ideas about femininity and masculinity and invite them to reconsider their perceptions of women and men in South Africa.

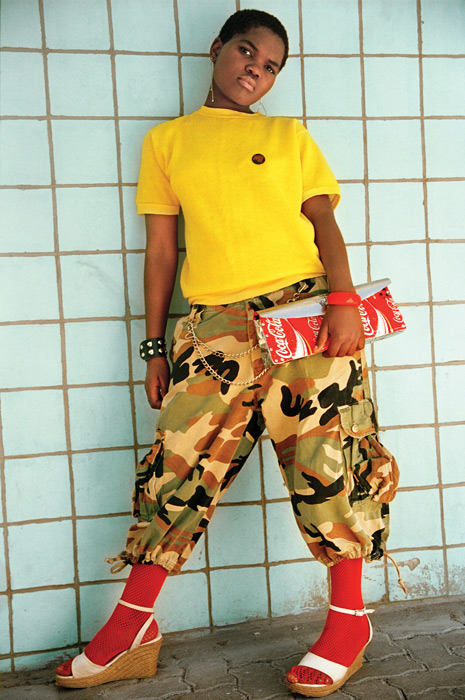

Finally, along the same lines, the series Beauty is in the Eye of the Beholder, by Nontsikelelo “Lolo” Veleko, reveals post-apartheid identitary changes among urban youths, who use clothing as a central tool in affirming individuality and creating new identities. The street is thus an inexhaustible source of inspiration for this young photographer, who, like Muholi, was trained at the Market Photo Workshop. Far from being anecdotal, these portraits are truly a sign “that South African young people have not only seized their own freedom but have easily appropriated the open field offered by the absence, until recently, of a typically South African urban style.”5

Translated by Käthe Roth

1 Marjorie Bull and Joseph Denfield, Secure the Shadow: The Story of Cape Photography from its Beginnings to the End of 1870 (Cape Town: Terence McNally, 1970).

2 Subotzky’s Web site reconstructs in minute detail the steps in making this work: subotzkystudio.com/ponte-installation-3/.

3 This exhibition was reviewed in issue 90 of Ciel Variable.

4 William J. Spurlin, “Emerging ‘Queer’ Identities and Cultures in Southern Africa,” in John Charles Hawley, ed., Postcolonial Queer: Theoretical Intersections (Albany: State University of New York Press, 2001), p. 186.

5 Christine Eyene, “Lolo Veleko – la rue comme tendance mode,” Afriscope (January 2011) (our translation). afriscope.fr/Lolo-Veleko-la-rue-comme-tendance.

Further reading

Diserens, Corinne. Chasseur d’ombres. Santu Mofokeng: Trente ans d’essais photographiques. Munich: Prestel; Paris: Jeu de Paume, 2011.

Diserens, Corinne (ed). Appropriated Landscapes: Contemporary African Photography from the Walther Collection. Göttingen: Steidl, 2011.

Enwezor, Okwui (ed.). Events of the Self: Portraiture and Social Identity: Contemporary African Photography from the Walther Collection. Göttingen: Steidl, 2010.

Garb, Tamar (ed.). Figures and Fictions: Contemporary South African Photography. Göttingen: Steidl; London: V&A Publishing, 2011.

Grantham, Tosha (ed.). Darkroom: Photography and New Media in South Africa since 1950. Richmond: Virginia Museum of Fine Arts, 2009.

Newbury, Darren. Defiant Images: Photography and Apartheid South Africa. Pretoria: unisa Press, 2009.

Peffer, John. Art at the End of Apartheid. Minneapolis: University of Minnesota Press, 2009.

marketphotoworkshop.co.za / goodman-gallery.com / gallerymomo.com stevenson.info / walthercollection.com

Érika Nimis is a photographer and historian. She has written numerous articles and three books on the history of African photography. Currently, she is an associate professor in the Department of History at Université du Québec à Montréal (UQAM), where she teaches African history.