[Fall 2012]

By Charles Guilbert

Sometimes, thanks to a curator’s insight, a group exhibition be comes a work of art in itself. This is the case for “Chronicles of a Disappearance,” in which John Zeppetelli not only presents five artworks of an extraordinary density but, in bringing them together, weaves networks of meaning that greatly strengthen each artwork.

Zeppetelli began his research on disappearance by looking at a work that, for all sorts of reasons, could not be exhibited: Where We Come Fromby Emily Jacir, a Palestinian artist who documents activities that she undertakes in the Occupied Palestinian Territory at the re – quest of refugees, because her American passport gives her privileged access there. The disappearance that interested Zeppetelli is linked to subthemes such as absence, borders, displacement, and the passage of time. Inspired by this work – which, in the end, “disappeared” from his project – and by the film by Palestinian Elia Sulieman (from which he borrowed the exhibition title), Zeppetelli became interested in a thematic grouping rather than a single theme, which led him to connect the works in the exhibition by creating multiple points of coherence.

In Jacir’s work, as in the five works finally chosen, a socio-historical reality serves as the point of departure for addressing the notion of disappearance. By inference, the documentary approach often gives rise, in contemporary art, to works that are dry, didactic, or illegible. Here, this is never the case, as all of the chosen artists have a well developed sense of storytelling, synthesis, and poetry. Their works, aiming to bring human fundaments to light and situated in the perspective of re-creation, even take on a mythic dimension.

To the thematic grouping corresponds a geographic circuit with the United States at its centre. The most disturbing works in the exhibition, those by Philippe Parreno, Taryn Simon, and Omer Fast, survey the American space by describing from completely different angles the violence rooted there and the effects of this violence, notably on countries such as Iraq, Afghanistan, and Pakistan. The other works evoke Mexico and Cuba, neighbouring countries with which the United States has a tense relationship. This inscription in space brings into play a fascinating series of political, historical, and cultural resonances.

In a seven-minute film titled June 8, 1968 (2009), Parreno portrays the journey of the train containing the remains of assassinated American senator Robert Kennedy. Inspired directly by photographs taken at the time by Paul Fusco, Parreno places alongside the train tracks immobile men, women, and children paying homage to the politician who had been a presidential candidate at the time of his death. By eliminating from the filmed scenes the flags omnipresent in photographs of the time but nevertheless playing the game of historical reconstruction, he creates a work totally in suspense. Because the camera often takes the point of view of the train locomotive, we see gazes turned off-screen and seeking to capture the passage of death. The result is a disturbing encounter with the viewer in which a double disappearance is at issue: that of the death of a man and that of the signs of this death.

The work might have been ruined by repetition if Parreno had not so carefully used cinematographic language to create gaps in the procession and thus animate the spectacle of the void. Through sound, Parreno draws our attention to the transition from presence to absence by using various audio strategies to make us aware of the locomotive, a sign of death. Sometimes we enter the tumult of its mechanical workings and then, suddenly, the sound cuts out for no obvious reason. We hear a subtle rumble in the distance. Then we are caught up by a strident screeching noise when the train slowly crosses an urban area. Other sounds occur in counterpoint: the wind whipping the grass, a strange piercing sound when a sunbeam crosses through a tree seen from a low angle. It all ends in complete silence: that of a woman, alone in a boat, suspended in waiting.

To this audio exploration responds a variation in the shooting angles that breaks the continuity of the travelling shots from the locomotive. A sort of wavering takes us from one scene to another according to a very free logic. Some are striking, such as the one of a woman in a bikini standing alone to watch the train pass.

When the film abruptly stops, the lights come up and we find that the floor of the room is entirely covered with bright-red wall-to-wall carpeting. The experience of the space in which we find ourselves raises a host of questions. What is this room with the red carpet? Is it an official place? A ceremonial place? A site of blood and violence? Then the lights go out . . . and we return to fiction.

The tension between reality and fiction is at the heart of 5000 Feet Is the Best (2011), a twenty-seven-minute film, both labyrinthine and fluid, in which Omer Fast interweaves interviews with two U.S. Army drone operators, one real and the other one fictional. The interview with the latter, which takes place in a hotel room, is repeated, but each time there is a slight discrepancy that opens up to other stories, some directly linked to the work of the drone pilot, others apparently digressions. “Is a drone operator a true pilot?” This question, which returns insistently during the interview, highlights the shift from real war to virtual war, as a bombardment in Afghanistan can today be conducted from Las Vegas. In an off-screen voice, the real drone pilot relates his need to play video games for a long time when he gets home from a day at work, thus transitioning imperceptibly from real war to game. He also describes the serious psychological pain that his work causes him, which is called “virtual stress.” Against this account, Fast ironically juxtaposes images that lead to a reversal of perspective and, by this very fact, encourage a new awareness. For example, as the pilot describes manipulating the weapon, called Predator, we follow, from a high angle, a young American bicycling through a huge modern housing development or a small American family going to the country.

As much by the structure of shifts and displacements as by the mise en scène, notably through the erratic gestures made by the fictional character, Fast exposes the strangeness, disorientation, and dismay resulting from this deterritorialized war. He also shows how, with this high-technology weapon, used to make the other disappear, all sense of reality tends to disappear.

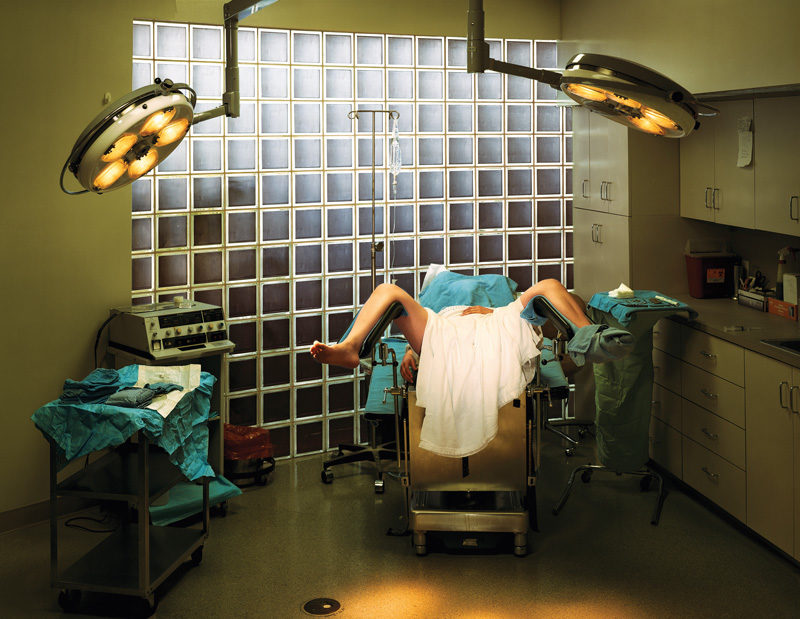

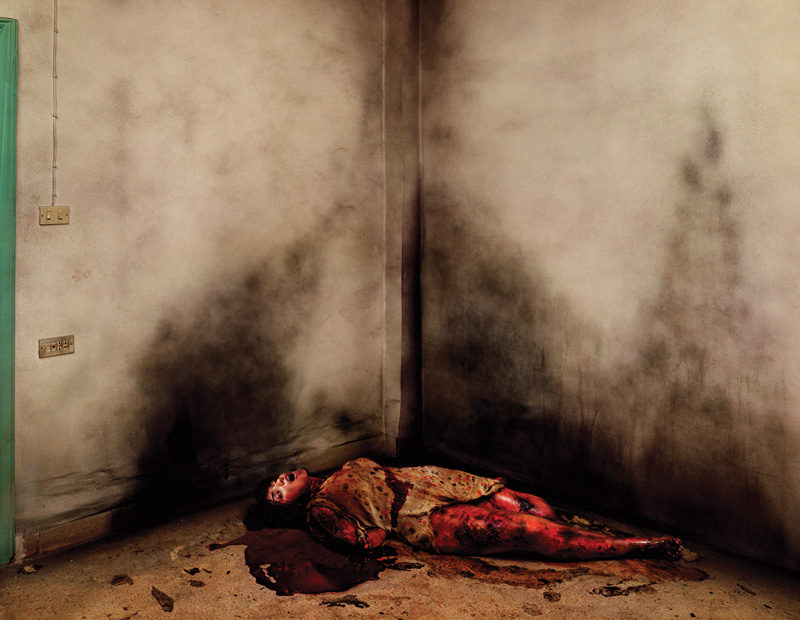

A sense of derealization is also distilled in the masterful work by Taryn Simon, An American Index of the Hidden and Unfamiliar (2007), of which nineteen photographs accompanied by texts are presented (there are seventy in the complete series). In often static, spare, even clinical framings, Simon reveals normally inaccessible places (a cryostasis institute, the room at JFK Airport where organic waste intercepted at customs is collected, a storage facility for nuclear waste, and so on), taboo phenomena (a Braille edition of Playboy, hymenoplasty, and so on), or people in extreme positions (an Oregon man with bone cancer who has legally obtained a prescription for pentobarbital enabling him to commit suicide, a prisoner on death row, and so on). These images are accompanied by enthralling explanatory texts that enable us to both understand the image and situate it in a much broader social, political, and economic context. Through an accumulation of dates, prices, measurements, and statistics, Simon, whose tone is almost outrageously objective, evinces profound irony: as she highlights the extravagance and rarity of what is found in her images, she elicits a strong rejection of American excess and drifting. Such excess is, above all, that of a science that, in an attempt to control everything, leads to disease, imprisonment, madness, and death, and of a legal system that, in leading to exclusion and isolation, creates all sorts of forms of disappearance. It is thus not surprising that a number of images focus on the theme of the border (blindness, customs offices, hymen) and the motif of enclosed space (cage, aquarium, laboratory, prison, quarantine room, fenced-in hunting ground). Through these, Simon encourages us to both meditate and be vigilant.

The other works in the exhibition encourage a similar sense of awareness. A second work by Simon, Zahra/Farah, sensitively addresses the interconnected fates of two Iraqi women, the first of whom was raped and killed by American soldiers. In Opus, José Toirac reduces a speech by Fidel Castro to the litany of numbers that it contains, proposing a reflection on the links among lyricism, rationality, and ideology. Teresa Margolles, in Plancha, gives a poetic rendering of the drop-by-drop evaporation of water from a Mexican morgue that had been used to wash people who died a violent death.

Each of the works in this exhibition immerses us in the anxiety underlying any disappearance, leading us to rediscover a position of amazement vis-à-vis reality and a desire to do something about it.

Translated by Käthe Roth

Charles Guilbert is an artist, writer, and critic (charlesguilbert.ca). His artworks have been presented in Quebec and abroad, including at the Musée d’art contemporain de Montréal, the Manif d’art in Quebec City, the Casino Luxembourg, and the Metropolitan Museum in Tokyo.