[Winter 2013]

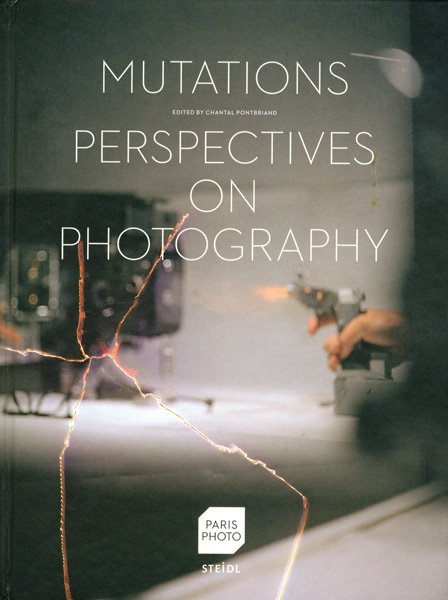

Mutations:

Perspectives on Photography / Perspectives sur la photographie

Chantal Pontbriand

(edited by / sous la direction de)

Göttingen and Paris: Steidl and Paris Photo, 2011, 414 pp.

Mutations : Perspectives sur la photographie / Perspectives on Photography, the major publication marking the 2011 edition of the Paris Photo biennial exhibition, is an omnibus collection of current thinking about photography theory and recent photo-based art. Edited by Chantal Pontbriand, founder and editor of the now defunct (and still much lamented) Montreal-based journal Parachute, Mutations marks an important, multivalent account of the state of art photography today. It should take a place alongside such recent collected volumes as Photography Theory (ed. James Elkins) and The Meaning of Photography (eds. Stimson and Kelsey). Although published under the auspices of Paris Photo (the major festival hosted in the France capital), Mutations is an autonomous publication that does not function solely as a catalogue of the festival’s exhibitions; it marks the first of a planned series of regular scholarly publications to be produced by Paris Photo.

The underlying premise of Mutations is that in the current age of social media, with citizen photojournalists, the growth of the art market for photography, and the general ubiquity of images, photographic practice is in a state of intense flux. As Pontbriand explains,

“The technologies of the image, in their current evolution, transform the idea of the image being a static thing, an object a form inherited from the perspectivism and rationalism of the Enlightenment. The image becomes flexible, polymorph, more than ever temporal, but also corporeal. The image participates in that culture of touching specific to our societies, which trumps the era of the visual and its iconic authority. The image traverses the body, the bodies. Its biopolitical dimension is stronger than ever. This new reality of the image changes the conventions of photography, its practitioners, museums, archives, libraries and media.” (p.13 English edition)

In Pontbriand’s view, this period of dynamic flux provides an optimum moment to pause and take stock of current thinking about and practice in photography. To this end, she asked dozens of thinkers to give their impressions of photo-based practice today and predictions for its future. The list of contributors is impressive. From across generations, they include theorists Hal Foster, Victor Burgin, Allan Sekula, and David Campany; curators Christopher Phillips (ICP, NY), Roxana Marcoci (MOMA, NY), Clément Chéroux (Centre Pompidou), Hans Ulrich Obrist (Serpentine), and Carles Guerra (MACBA, Barcelona); and artists Taryn Simon, Daido Moriyama, and Yto Barrada, among dozens of others. Although Mutations is weighted toward the art scenes of Europe and New York, it also includes some cross-disciplinary contributions, including those by sociologist Saskia Sassen and playwright Rabih Mroué, and the featured photography is more fully representative of the world.

Rather than commissioning specific essay topics, Pontbriand adopts a more open-ended and less restrictive approach that reflects the “flexible, polymorphe” state of photography today. She asked contributors to think about photography’s present and future in relation to four central themes: “Geography,” “Technology,” “Society/Media,” and “Body.” These loose categories provide the volume’s organizational structure (although, as Pontbriand acknowledges, they are rather amorphous, allowing for porous borders with ideas and artworks flowing from one theme to another). Each section opens with an essay or photo essay introducing the theme, followed by several specific ruminations ranging from polemics to conventional curatorial studies of an individual photo-based artist. The sheer size of the volume is daunting. It features works by dozens of photographers and sixty short essays (thirteen under the heading “Geography,” nineteen under “Technology,” twelve under “Society/Media,” and sixteen under “Body”).

“Geography,” the first section, includes considerations on transnationalism and the local. Saskia Sassen opens the section by looking into the ways that “both geography and photography obscure as much as they make visible” (p. 37 English edition). The subsequent essays are informed by various aspects of postcolonial discourse and address familiar figures from the history of twentieth-century photography and from the international biennial circuit, past and present: Daido Moriyama, Yto Barrada, Walid Raad, and Seydou Keïta.

Peter Weibel (chairman and CEO of the KM/Center for Art and Media in Karlsruhe) opens the “Technology” section with an essay that contextualizes recent participatory and interactive media art within the history of the neo-avant-garde since the 1960s. In doing so, he also historicizes the photograph:

“20th century art was defined by the paradigm of photography. In the electronic world and its electronic media, the art of the 21st century will be defined by the paradigm of the user and the net. With the advent of photography, the visual artist lost his monopoly on the image. Now artists no longer have the monopoly on creativity. Following on the heels of participative and interactive media art, the turning point between visual and social media, visitors as users now generate or compile online content. From consumers they become producers and programme designers and thereby competitors for the historical media monopolists: television, radio, and newspapers.” (p. 142, English edition)

Despite observation, the essays that follow largely address the (predictable) subject of new media in the gallery. I was surprised to see few images here that fall outside the conventional art market. Nonetheless, this section also includes a couple of thought-provoking essays that tangentially touch on the theme. Art historian Hal Foster takes issue with one of the sacred texts of photography studies, Roland Barthes’s Camera Lucida, by comparing it to Michael Fried’s 2008 Why Photography Matters as Art as Never Before. The unlikely comparison allows Foster to argue that that Barthes’s influential book, with its emphasis on the punctum as a vestige of trauma, has the conservative effect of “distract[ing] us from the social field of photography” (p. 152, English edition). Related to this concern, Christine Frisinghelli, in her essay, offers a clear and insightful discussion of photography and the art market.

The engagement with the social, seen in Foster’s and Frisinghelli’s essays, is the central focus of the third section of Mutations, “Society/Media.” (Indeed, at times, these two sections all but merge together.) In her introduction, art historian and critic Elisabeth Lebovici historicizes the role of photography and recent social media in identity formation. Her essay is followed by examinations of documentary and subjectivity. Allan Sekula’s essay, “Eleven Premises on Documentary and a Question” (originally published for the 2006 Jeu de Paume exhibition Document), provides a particularly important statement for anyone involved with social documentary photography and the critical literature on it. In his manifesto-like treatise, Sekula – like Foster – sounds an alarm over the disappearance of the social in a neo-liberal milieu.

The final section, “Body,” opens with excerpts from American artist Taryn Simon’s A Living Man Declared Dead and Other Chapters. Drawing on the rhetoric of the archive, Simon’s influential series (is it possible to go to any major city in the world and not see this work?) provides a powerful, nuanced, and witty image of such linked themes as community, human rights, and intergenerational connections. The bodies that she shows us are joined by resemblances and marked by history. In subsequent essays, “Body” provides a rubric for thinking through gender, sexual, and racial construction while returning to the borders between the social and representational that appear in the preceding two sections. Indeed, art historian Jean-François Chevrier’s contribution to this section adapts the theme to a consideration of the history of magazine photography in France and beyond.

Across its four themes, Mutations offers a complex picture of where photo-based art is today and where it may be going. This is an ambitious and important publication that will be pored over by anyone engaged with contemporary photo-based art. But, like all publications emerging out of biennials and other major international exhibitions, Mutations does not provide a straightforward and concise scholarly narrative about the direction of recent photo-based art. Instead, reflecting the rich diversity and energy of the moment, it invites the reader to join a loud, wide-ranging, open-ended, and intellectually rich debate.

Carol Payne is an associate professor of art history at Carleton University. She is author of the forthcoming The Official Picture: The National Film Board of Canada’s Still Photography Division and the Image of Canada, 1941–1971 and co-editor (with Andrea Kunard) of The Cultural Work of Photography in Canada.