By Bénédicte Ramade

The two last decades have seen the growth of a complex phenomenon: exhibition reproductions. A reprise produced as the inclusion of a “period room” doesn’t have the same effects as a complete restaging of a famous precedent in twentieth-century art history. And the educational value varies depending on whether the reproduction is maniacally accurate, such as Live in Your Head: When Attitudes Become Form, Harald Szeemann’s legendary exhibition initially presented at the Berne Kunsthalle in 1969 and restaged by the Prada Foundation in its eighteenth-century Venetian palace in 2013, or a partial revival, such as the one presented at the Zurich Kunsthaus in 2010 of Pablo Picasso’s first retrospective in 1932.1 At first practised out of curiosity in the hope of finding a buried secret, the reproduction of exhibitions has become emblematic both of patrimonialization and of the advent of curatorial studies. One might see this as a sign of opportunism, or even laziness – if not a profound admission of institutional weakness in search of past brilliance. Two recently revived exhibitions highlight all of these issues: Family of Man, Edward Steichen’s humanist vision inaugurated in 1955 and now installed permanently in Luxembourg, and New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape, an exhibition presented in 1975 by William Jenkins at the George Eastman House in Rochester that went on international tour from 2009 to 2012.

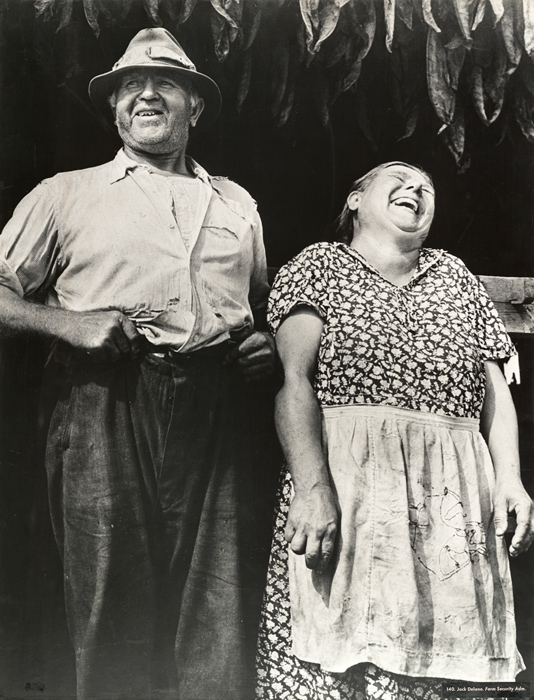

Family of Man, an extraordinary event, became a phenomenon in which the quantifiable often exceeded the aesthetic: during its career, which stretched over a number of years, it drew nine to ten million visitors in the more than thirty countries it visited. And there are more numbers: to create this object whose final form included 503 images, Steichen and his assistant, Wayne Miller, apparently looked at some two million photographs taken by both professionals and amateurs. Of these photographers, there remained only 273, some well known, such as Henri Cartier-Bresson, Diane Arbus, Ansel Adams, and Dorothea Lange, and others almost anonymous. It was not so much the quantifiable parameters of this exhibition that made it famous and attractive, however, but the unusual and audacious mounting by Paul Rudolph and Steichen, which superimposed images on others, hung some from the ceiling, and made reframings or plays on scale to create a true visual environment devoted to portraying humanity. With an obvious political motive in the midst of the Cold War,2 Family of Man offered a universalist, fairly traditionalist vision of humanity through the ages and through cultures, as well as in themes such as work and sadness,3 while at the same time promoting American values. If this piece of history finally came to rest at the Clervaux Castle, it was because Steichen, the illustrious Luxembourgish, wanted to favour his country of birth with his most famous contribution to art history. Beyond the question of copyright, the photographer (and director of MoMA’s photography department) allowed himself to think of the collective and thematic exhibition as a self-made meta-work to which he had in fact given his own name, thus patrimonializing this version.4 Presented a number of times since 1994 in the medieval castle, Family of Man recently received a major restoration and, especially, a reinscription of the images in an exhibition design that is inspired largely by the mounting that was visionary for its time.

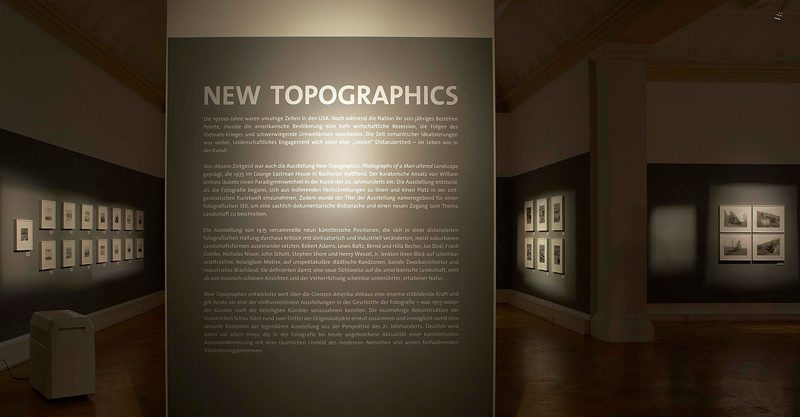

New Topographics: Photographs of a Man-Altered Landscape did not have the same fortune, and its history is written counter to its physical existence. Indeed, the eyewitnesses from 1975 who contributed to the imposing eponymous catalogue published in 2009, when the event was reprised, all agree that the exhibition was not a success. There were few visitors, the press was circumspect, and the artists brought together by William Jenkins were little inclined to be grouped in a particular genre. Yet, despite its slim catalogue and a pared-down selection of only ten photographers,5 New Topographics established a new nomenclature for the American landscape and gradually revitalized the genre as one that was less heroic and more realistic than that inaugurated by the pioneers of the category (from Timothy O’Sullivan to Ansel Adams). A few years after the first oil crisis (and the first challenging of the Western – especially American – way of life), midway through a decade marked by environmental debates, the reformulation of the identity of the American landscape by sanctifying the banality of its interstitial spaces (suburban, industrial, and urban peripheral zones) had the effect of freeing the landscape from the question of nature while assuming an analytical and critical photographic gaze. The exhibition did not have the dazzling staging of Family of Man; unadorned, it stretched out along an almost continuous median line on the walls of a single gallery. Each series was presented following the previous one without provoking a dialogue. The attempt to persuade the viewer was nowhere near as elaborate and complex as the visual proselytism of Family of Man. On the contrary, New Topographics played on its intellectual nature and its reluctance to make too many claims. It must be said that in three decades the prescriptive roles of the institution and the curator had greatly evolved; however, if reserving the act of interpretation for the viewer expressed singularly different perspectives than those intended by Steichen, it nevertheless entrusted responsibility to the one who was looking. This is also one of the main qualities of the reprise. It is disturbing, however, to see an exhibition that is so unspectacular – even off-putting – on the visual level reconstructed, and the legitimate question arises of whether there is a need for this undertaking.

It is tempting to relive history through these more or less faithful reconstructions, to yield to nostalgia for a time when exhibitions wrote history and the viewer was not a cultural consumer, but more an interlocutor. Neither of these exhibitions is an identical reproduction of its model; the decision was made to exhibit fewer works than the original – without, however, resorting to sampling. The impression of similarity is produced by an overall effect conveyed by resemblance. What should we think of this bias toward ambience without the reproduction rising to the level of archival meticulousness? Until 2013, with the identical restaging of Szeemann’s exhibition, interpretation was appropriate and could be regarded as satisfactory, but a new standard was established with the reproduction to scale, with an almost legalistic exactitude, of both the volumes of the original spaces and the works, now disappeared, that they hosted in 1969.6 Family of Man and New Topographics avoided such lockstep likeness, setting aside the paragon of the ready-made exhibition and thus posing the question of the status of an interpreted reconstruction – especially because these exhibitions had a fundamental political subtext that is no longer relevant. Both – one with the project of disseminating American values in the midst of the Cold War; the other, the visual and intellectual deconstruction of the founding principles of the American landscape (which, as we know, had previously been composed in the nineteenth century following a coherent political program) – were far from having solely aesthetic concerns. In this, they contrasted with, or example, When Attitudes Become Form, a post-’68 exhibition that was focused essentially on formal and conceptual issues in contemporary art rather than on the socio-economic upheavals of Western youth at the breaking point. This exhibition could indeed claim to be a ready-made, almost impermeable to its socio-political context and reproducible per se.

The scope of Family of Man and New Topographics went largely beyond such strictly aesthetic and artistic concerns. A social phenomenon, Family of Man is understood today, at a distance from its original mission, more as a viewer’s experience and a reflection on the evolution of notions of humanity and the values of which it is made.7 At the same time as it confirms the obsolescence of Steichen’s basis of work and references, in its current form the exhibition helps make it possible to experience a legend that had been tucked away in archives. It makes it possible to rethink the immersion of the exhibition path without its coercive issues and to consider the visual proposition as an overarching work; Family of Man can be seen for the exhibition that it is. But this isn’t possible with New Topographics, with its black-and-white medium-format photographs drily aligned, refusing to resort to effects. Here, the photographers’ approach prevails over the curator’s discourse. The surprise of New Topographics resides not in its formal eloquence but, on the contrary, in its almost exaggerated visual reticence. Cerebral, New Topographics refuses to direct the viewer, letting its intelligence make connections with the viewer-eyewitness, whereas Family of Man orchestrates popular wisdom at the risk of flattening out everything, the works becoming almost secondary. They are, above all, images.

With its reopening to the public in an exhibition design more similar to the MoMA original, the Luxembourg version of Family of Man proves right the recent rereading done by a communications professor at Stanford, Fred Turner, in a brilliant article published in 2012, “The Family of Man and the Politics of Attention in Cold War America.”8 In his remarkable analysis and rehabilitation of this anti-conformist approach, Turner shows how Family of Man intersects with current reflections on the viewer’s experience and freedom. This essay offers a perfect frame within which to think about the pertinence of conserving such an exhibition, stepping beyond the strictly political readings that would reduce it to simply an archaeological curiosity. In 2014, Family of Man no longer exerts the same ideological program that inspired its structure, but it may reshuffle the cards of a history of art institutions and their social stakes at a time when they no longer truly direct history. The utopia of developing the visitor’s personality through Steichen’s choices, however peremptory, and orchestration also makes it possible for the enterprise of reproduction to surpass the simple remake effect and the opportunism that might then underlie it. The added value for contemporary viewers resides in this unexpected experience, as was the case with When Attitudes Become Form in 2013. For New Topographics, the experience is less conclusive because of its almost anti-exhibition form; it functions essentially on a more nostalgic archaeological mode.

Replaying history does not always nourish intellectual progress, and sometimes it may be simply the pretext for redemption: because an exhibition will never have been seen often enough or well enough, it would have the right to a second go-round in order for viewers to affirm what they had not been able to see before. The undertaking seems decidedly more vain than that of embracing one’s obsolescence almost gallantly in order to make the ideal prism for analysis of a present that is a bit stuck when it comes to curatorial creativity.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 The exhibition’s circulation was funded by the U.S. State Department with information in a method worthy of propaganda.

3 In Mythologies, Roland Barthes devotes an article to Steichen, essentially reproaching him for his anhistoric vision (“La grande famille des hommes,” Mythologies [Paris: Seuil, 1957]). Since then, critical readings have constantly analyzed the quirks of Family of Man, including its Manichaeism, its paternalism, and its very debatable racial conception of peoples.

4 This was one of the three versions that toured Europe between 1955 and 1962.

5 Robert Adams, Lewis Baltz, Bernd and Hilla Becher, Joe Deal, Frank Gohlke, Nicholas Nixon, John Schott, Stephen Shore, and Henry Wessel Jr.

6 Given that Szeemann had assembled numerous process-related practices for Live in Your Head, many of the works did not survive after the exhibition. In agreement with the artists and rights holders, some of them were completely remade. The basics of the pieces were found and reassembled for the event. However, some works that had disappeared were not replaced, and their place was left vacant, indicated by a dotted-line contour on the floor where they would have been found.

7 It is, for example, a particularly fertile research basis for rereadings of gender.

8 Fred Turner, “The Family of Man and the Politics of Attention in Cold War America,” Public Culture, vol. 24, no. 1 (2012), 55–84.

Bénédicte Ramade is an art historian. She is currently working on publishing her doctoral dissertation on the critical rehabilitation of American ecological art. A journalist and art critic, she has developed expertise on issues of nature and ecology in contemporary art practices, which she brings to reality as an exhibition curator (Acclimatation, Villa Arson, Nice, 2008–09; REHAB, L’art de re-faire, Fondation EDF, Paris, 2010–11).