By Ariane Noël de Tilly

Stan Douglas’s earlier productions include Every Building on 100 West Hastings (2001), a nocturnal panorama of a block of buildings situated in a poor Vancouver neighbourhood, and the series of four photographs Crowds & Riots (2008), depicting reconstructions of crowd scenes and riots that took place in Vancouver during the twentieth century. In the spring of 2014, he unveiled three new projects exploring another chapter in the history of his hometown: the post–Second World War period. Conceived under the motto “History will not be silent,” these projects took diverse forms: a play, an exhibition, and an iPhone and iPad application produced in collaboration with the national Film Board of Canada. Douglas and his collaborators used various procedures for representing a past in which events, places that no longer exist, and fiction intermingle.

Douglas is known for the unique form of narrativity that he has employed in video and film installations such as Nu•tka• (1996), which revisits the colonial past of British Columbia, and Klatsassin (2006), about the gold rush in the nineteenth century. The stories that he tells have neither linear structure nor beginning and end, and they shed light on forgotten places and events. Many of his films are composed of a number of episodes presented in permutations dictated by algorithms that help to blur the lines of history.1 in his three recent projects, the narrativity is fragmented, although it does not obey mathematical laws. it is not surprising that two places that no longer exist – the Hotel Vancouver and Hogan’s Alley – served as the anchoring points common to the different narrativities presented. The Hotel Vancouver, situated in the western part of downtown, housed several hundred Second World War veterans and their families until 1948. it was demolished the following year to make way for a parking lot. Hogan’s Alley was in the eastern part of downtown – more precisely, in Strathcona, Vancouver’s oldest residential neighbourhood, home to mainly multiethnic families. For several decades, before and after the war, this neighbourhood was also where the police turned a blind eye to contraband, gambling, and prostitution. Hogan’s Alley was razed in 1968 to make way for one of the exits from the Dunsmuir Viaduct.

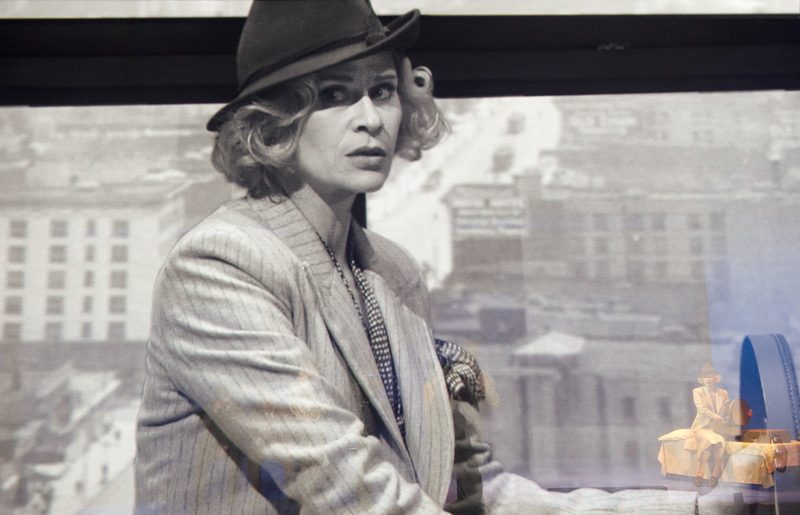

Although Douglas’s three projects evolved simultaneously, the first to be presented to the Vancouver public was Helen Lawrence.2 Conceived by Douglas and written by Chris Haddock, the play had an excellent cast and great staging. The play, depicting a city being reconstructed just as people are undergoing their own personal reconstruction, portrays the anguished atmosphere provoked by the postwar economic situation. Each character tries to live as best as he or she can: friendships form, couples break up, debts accumulate, people mourn, veterans try – with great difficulty – to reenter the job market, and so on. Despite the hard daily realities that these individuals face, the general impression of the play is that the characters, especially the female ones, are highly stereotyped. Also, the fact that these people’s stories are told in a linear fashion was a bit disconcerting for people familiar with Douglas’s work.

Helen Lawrence has a cinematographic feel: it borrows from the film noir aesthetic and uses projections of prerecorded images shot in real time. The moving images are projected on a huge translucent screen placed downstage. Three cameras positioned behind the screen are manipulated by the actors who are not performing in the current act. The result of this combination of live theatre and film projections is certainly very interesting visually because it gives the audience a closeup view of the actors’ movements and expressions, to which are added images of different places in Vancouver. in fact, during the play, the audience has the sense of watching a film being made, and it is through this aspect that Stan Douglas’s visual and cinematographic vocabulary becomes recognizable.

The exhibition Stan Douglas: Synthetic Pictures, on display at Presentation House Gallery in north Vancouver from March 21 to May 25, 2014, offered another point of access into the postwar history of Vancouver; in these works, Douglas attempted to replicate the practices of certain photographers of the period. The exhibition’s title immediately gave viewers an idea of what they would see: artificial images, created or reconstructed with the use of digital technology. The exhibition, curated by Helga Pakasaar, brought together recent series of photographs and digital reconstructions produced by the artist, who, since creating the series Crowds & Riots in 2008, had been working exclusively with digital photography.3

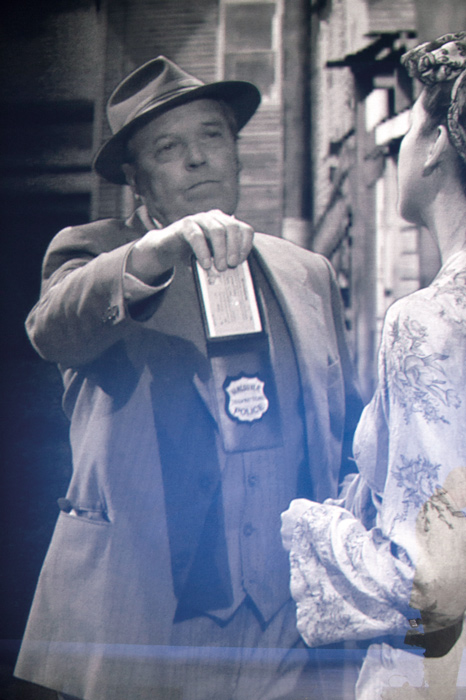

The central gallery in Presentation House Gallery contained five prints from the series of black-andwhite photographs Midcentury Studio, produced in 2010. The series takes visitors back to the period after the Second World War. Douglas was revisiting a specific time in the history of photography: postwar photojournalism. As he explained, the series “chronicles the career of a photographer who was introduced to his craft during the war and tried to make it into a business in the postwar period.”4 He was inspired, among other things, by the work of the self-taught American photographer Arthur Fellig, better known as Weegee, and the royal Air Force veteran Raymond Munro, who arrived in Vancouver in 1949 and, without any experience, was hired as an aerial photographer by a local newspaper. Midcentury Studio is an exercise in style the result of which is a group of photographs addressing themes that were highly regarded at the time, such as fashion, technology, crime scenes, dance, and gambling and other corrupt activities. For example, Burlap, 1948 is a reconstruction of a crime scene in which the victim’s body has been covered with a jute tarp; Cache, 1948 shows an open trapdoor in a wall behind which are hidden playing cards, dominos, bottles of liquor, packs of contraband cigarettes, and money – everything needed for a night of gambling; Suspect, 1950 features a criminal who has just been arrested sitting in the backseat of a car, probably between his lawyer and a detective. The crime scenes and the way that the artist chose to photograph the subjects also evoke the codes of film noir.

In the west gallery, Hogan’s Alley (2014) was displayed along side digital reproductions of photographs of houses and buildings on Prior, Union, and Main streets, taken around 1968–69 and conserved in the City of Vancouver’s archives. The organization of photographs on panels bears a resemblance to the layout in Ed Ruscha’s book Every Building on the Sunset Strip, 1966. The difference in scale between the panels and Hogan’s Alley is striking and points out the distinction between the archival photographs and Douglas’s new work. At first glance, Hogan’s Alley looks like a high-angle black-and-white photograph of the alley. However, Hogan’s Alley is not a photograph taken by the artist, as the alley had been razed more than forty years before, but an image created from digital special effects. The nocturnal shot seems completely appropriate given that Hogan’s Alley came alive at night. However, the digital reconstruction presents it deserted, as if it was a ghost alley. A human presence is evoked by lights visible in various houses, and also by a yard furnished with round tables with chairs, a piano, and some stools, as if a crowd is about to arrive to see a show – or perhaps the concert has just ended and both the audience and the musicians have just left.

With Hogan’s Alley, Douglas chose to evoke a place, but to really grasp its sociological customs and characteristics, one must have seen the play Helen Lawrence or use the application Circa 1948. Hogan’s Alley is a visually very attractive work, but it is almost too perfect. every part of the image is excessively detailed. The final result of this digital editing gives the impression that the alley was very clean, that the space was perfectly organized, whereas historically it was completely dilapidated.

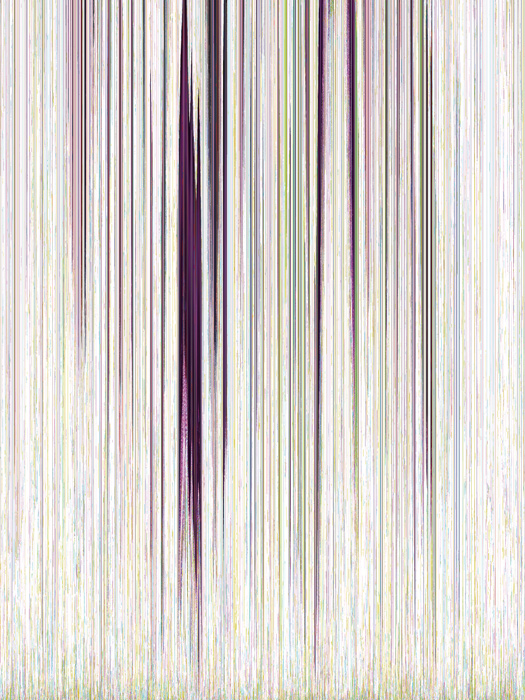

The visit to the exhibition at Presentation House Gallery ended surprisingly. in the east gallery, seven inkjet prints from the series Corrupt Files (2013) were on display. Whereas the other two galleries featured photographs or digital reconstructions with a historical content, Corrupt Files is a series of abstract works composed of effects that may arise at a time when a digital photograph is taken. The inkjet prints are, in fact, prints of code. The result is a leap toward abstraction, which Douglas had never previously addressed; above all, it marks a break in the artist’s approach, as it puts an end to all possibility of narrativity. These works, formed of lines of vertical colours, are reminiscent of modernist painting; thus, it is always possible to find references to history. However, in the context of this exhibition, Corrupt Files puts an abrupt end to a chapter of history that had just been revived.

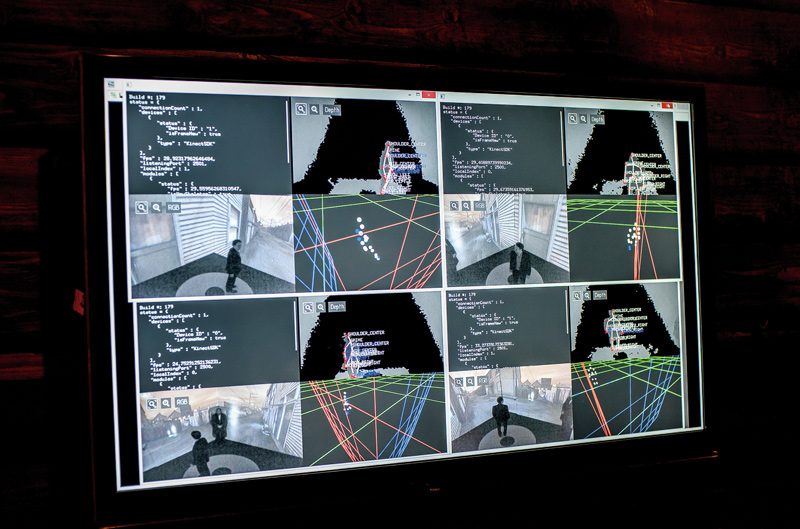

Finally, on April 22, 2014, Douglas and the National Film Board launched the application Circa 1948.5 This interactive, immersive 3D application uses video game technology, but Douglas denies that it is a game. He is very clear on this: for him, the application is not about killing zombies or accumulating gold coins, but about giving users an opportunity to grasp how and where people lived in Vancouver around 1948.6 The app gives a virtual introduction to the Hotel Vancouver and Hogan’s Alley. To a jazz soundtrack, users stroll down the alley and wander through the hotel, and they can click on bright objects to hear conversations among different people staying or working in the hotel or spending time in the alley. In Circa 1948, the history of people and places is not told in a linear fashion, as in Helen Lawrence. Nor do algorithms decide the order of the sequences – the user is in charge of choosing his or her path through this virtual world. These immersive and participatory dimensions are new in Douglas’s practice and give users an opportunity to decide on the course of history.

Douglas’s three recent projects that revisit, fragmentarily reconstruct, and reveal certain aspects of the history of Vancouver in the years following the end of the Second World War are complementary and function as a triptych: to better grasp and appreciate each fragment, it is preferable to have seen and experienced the others. Douglas and his collaborators call upon theatre, cinematography, photography, the digital, and the virtual to reconstruct two places that are now gone and reenact the activities that took place there in order to keep us from forgetting them. These different reconstructions also remind us that history, like any image, is a construction.

Translated by Käthe Roth

2 Arts Club Theatre Company, Vancouver, from March 13 to April 13, 2014.

3 Alexander Alberro, “An interview with Stan Douglas,” in Stan Douglas: Abbott & Cordova, 7 August 1971 (Vancouver: Arsenal Pulp Press, 2011), p. 15.

4 Stan douglas, “Midcentury Studio,” in Tommy Simoens (ed.), Stan Douglas: Midcentury Studio (Antwerp: Ludion, 2011), p. 7.

5 The application can be downloaded free of charge at the iStore. See also http://circa1948.nfb.ca/ to access the complete list of contributors.

6 Artist’s statements from the press kit for the application Circa 1948, http://onfnfb.gc.ca/fr/salledepresse/communiquesdepresse troussesmedias/?idpres=21173

Ariane Noël de Tilly holds a doctorate in art history from the University of Amsterdam and was a Postdoctoral Research Fellow at the University of British Columbia from 2011 to 2013. Her research deals with exhibition, dissemination, and preservation of contemporary art, and the history of exhibitions. She is a lecturer at Emily Carr University of Art + Design.