Vera Frenkel

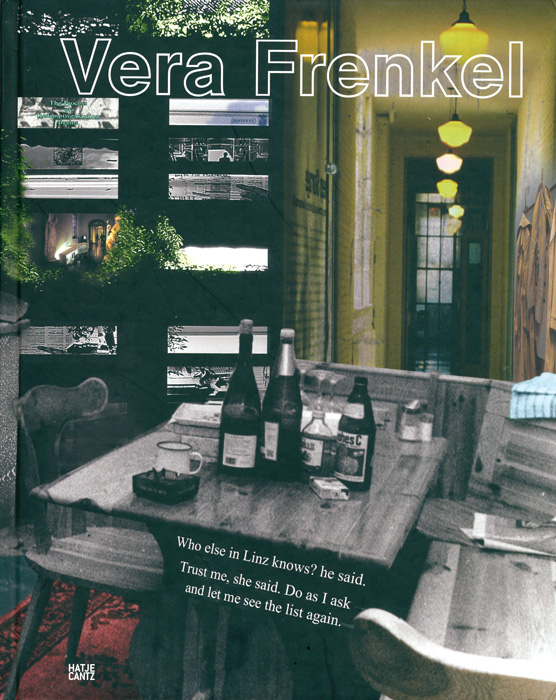

Ed. Sigrid Schade, Ostfildern: Hatje Cantz, 2013, 310 pp.

By Cheryl Simon

Vera Frenkel, a monograph published last year by German art book publisher Hatje Cantz, offers the most comprehensive study of this Canadian multidisciplinary artist’s work to date. Remarkable for its reach, the book includes twelve essays focused on nine projects completed over a forty-year span, their “travel histories” and some of their source texts, nearly three hundred illustrations of a broader selection of Frenkel’s work, and extensive biographical and bibliographical information. If the scope of the inquiry is extraordinary, so, too, are the efforts made by the contributors to this book to reconcile the dictates of art-historical accounting with the very different approach to historical representation that the artist enacts in her work. Frenkel’s work is fluid and dynamic, difficult to categorize, and nearly impossible to fix.

In early writings about the creative process, Frenkel made a distinction between the concepts of “fixed” and “interim closure” as different end-points in artistic and historical endeavours – a distinction that explains something of her thinking about history making. Favouring the latter term, she approaches her work as a continuous process of discovery, momentary resolution, reformulation, transition, and change. Her multimedia installations build factual and fictional fragments of images and texts, along with thematically related ephemera, into interactive narrative productions that explore real-life encounters with transition and change. Experiences of migration, exile, displacement, and loss and ways of knowing, remembering, and representing history are the principal interests driving her art practice.

Hers is a work of collection and dispersal in which the discrete elements within individual artworks are incomplete on their own terms, and are made sensible only through associations between other “traces” and “clues.” Art historian and essay contributor Anne Bénichou suggests that the viewer encounter the work as a type of mystery story – or, better, a nouveau roman – in which she must come to terms, as best she can, with the idea that truth is ultimately unknowable, or at least not known in any direct way.

Frenkel’s projects also unfold in different phases. Both concrete and conceptual elements of individual installations are reworked and reconfigured in later stagings, and sometimes find their way into completely new works. No Solution: A Suspense Thriller (1976–79), an early work exploring the relationship forged among truth, lies, and fiction in the production of knowledge began as an installation with slide projection and sound; video and video-puppet theatre were added to later incarnations. A much more radical transformation occurred when …from the Transit Bar (1992–96) and Body Missing (1994–2010), two video-installation works produced separately to address very different experiences of displacement and loss, were brought together in the Web version of Body Missing, launched in 1995. The effect was to reorient the specific interests of each work, expanding the reflections on migration and displacement taken up in …from the Transit Bar and shifting Body Missing’s investigation into the plundering of Jewish art collections by the Third Reich to encompass a critical reflection on the metaphysics of absence/ presence, and to inaugurate an online exchange sharing information about the stolen artworks. …from the Transit Bar and Body Missing lie at the heart of this publication – both literally and conceptually. Although the themes explored in the various iterations of these two projects are certainly discernible in some form or another in all of the works gathered here, more significantly the approach taken by the contributors to this study mirrors the combinatory strategy enacted in the Body Missing Web site. The writers engage the projects selected for study as “interactive transit stations” in which the themes, questions, and forgotten and repressed histories fully developed in the Web project are anticipated, expanded, or revisited in earlier and later productions.

Conceived to respond to the location and historical circumstances within which it was staged, …from the Transit Bar was originally presented as a site-specific video installation and fully functioning piano bar at Documenta IX (1992). The first presentation since the Berlin wall fell in 1989, the 1992 exhibition also coincided with a dramatic rise in immigration to Germany as conflict escalated in the former Yugoslavia. Whereas the stories of immigration and homelessness that played on the video monitors of the Transit Bar made the installation into a gesture of witnessing, the bar provided a place of community – a home away from home, so to speak.

In the preamble to the essay that Frenkel contributed to this publication, she notes that the Documenta presentation marked a culminating point in a string of coincidences and events that linked her personal history to that of Germany before and since the start of the Second World War, the first of which was her birth on the same night as Kristallnacht in Bratislava, on November 10, 1938. Observing the feeling of connectedness and “the shared longing for reconciliation” among the patrons of the Transit Bar, Frenkel proposed that the Kassel experience was a homecoming.

If ideas of migration, exile, and loss provide the conceptual foundation for …from the Transit Station, absence is the theme most fully developed in Body Missing. In his contribution to the book, John Bentley Mays approaches this work as an elegy, a lament that “commemorates loss, registers absence, conducts the work of mourning in public” (p. 196). “What loss is being mourned?” Mays reminds the reader that the missing bodies to which the title of this work refers are not the paintings recovered at the end of the war from the Linz salt mine where Hitler hid them, but the artworks that were stolen and never found. In the end, Mays suggests, it is not the loss of these great works of art that Frenkel’s work laments, but what Jean-Luc Nancy calls “the singularity of every being.” Their absence registers the loss of all that has passed, all people, places, and things that are missing or gone.

The retrospective and relational reviews undertaken by the authors offer fascinating and affecting new insights into the issues, politics, and practices at play in Frenkel’s works. In her retrospective reading of String Works (1974), Frenkel’s pioneering experiment with telematics, Dot Tuer discerns the “poetics of absence” in embryonic form. Although, at the time of its staging, this nine-hour teleconferenced interactive performance was celebrated for its distance-shrinking, real-time linking of participants in the CBC’s Montreal television studio with others in its Toronto studio, in hindsight, the reduction of connectivity in virtual sociality becomes more apparent. The retrospective viewing of String Games alongside Body Missing clearly makes this loss even more significant, but the archival view, which is the perspective that recognizes the very particular material dimensions of Frenkel’s work, is more affective still. In considering the documentary lens through which one views the String Work performance at present, the performers become “agents of remembrance, who by reaching out to each other across time and space guard against their own disappearance from the screen and in doing so, guard against oblivion” (p. 47).

Since the late 1980s, Frenkel has developed a body of works that approach the subject of loss as an epiphenomenon of late-stage global capitalism. Reacting to the emergence of the New Economic Order after the Reagan and Thatcher years, This is Your Messiah Speaking (1987 – 2012) used the forms and language of advertising to mock the rhetorical means by which corporate culture is sustained. Lampooning the discourse of corporate public relations, The InstituteTM:Or, What We Do For Love (1998–2006) responded to this same economic change as it impacted Canadian social and cultural policy. Initially conceived as a publishing project, The InstituteTM later served as the Web portal to a string of fictional retirement homes for mid-career artists located in hospital buildings abandoned in the wake of healthcare cuts. If, as Elizabeth Legge notes, The InstituteTM points to “the loss of a Canadian national vision,” Once Near Water: Notes from the Scaffolding Archive (2008–12) mourns the loss of an actual, physical view. The scaffoldings referred to in the project’s title frame the proliferating building sites for luxury condominiums on the lakeshore of Frenkel’s hometown, effectively blocking Torontonians’ visual access to the landscape that surrounds them. Sylvie Lacerte envisions the scaffolding archive as an “archaeological tale of a city buried deep beneath the greed of developers” (p. 247). It is the same for almost every other major city in the world. If, as the work observes, “Mapping greed is a thankless task,” it also seems endless.

In her introduction to this study, Schade observes the special problem that Frenkel’s work poses to publication in book form. Beyond the difficulty of translating moving-image and sound works into a static structure, the changing aspects of Frenkel’s practice are hard to equal. Reading relationally and retrospectively, in dialogue with the artist, her interlocutors, and the works themselves, Schade and her co-contributors have succeeded beautifully in reanimating this dynamic work, enacting, for themselves and their readers, the kinds of movements and encounters of mind and history inspired by Frenkel’s eloquent art.

Cheryl Simon is an academic, critic, and curator whose research interests include explorations of time in media arts and collecting and archival practices in contemporary art. She teaches in the MFA-Studio Arts program at Concordia University and in the Cinema + Communications Department of Dawson College, both in Montreal.