Dispatch: War Photographs in Print, 1854–2008

Thierry Gervais (ed.)

Toronto: Ryerson Image Centre, 2014, 96 pages

By Corina Ilea

From September 17 to December 7, 2014, Ryerson Image Centre presented the exhibition Dispatch: War Photographs in Print, 1854-2008, curated by Thierry Gervais, and marking the centennial of the First World War. The exhibition is accompanied by a publication that underscores the intricate connection between war and photography, as well as the not-so-innocent mechanisms of representation activated in recording, transmission, and shaping of conflicts in the visual field. Although photography and war have been interrelated for more than 150 years, visual strategies and technologies of representation have evolved over time. Editorial practices have influenced, transformed, and often determined the representation of conflict and war photography. Mirroring the structure of the exhibition, the publication highlights, parallels, and contrasts the use of original photographs and prints and their corresponding use in the press, underlining their ideological convolutions.

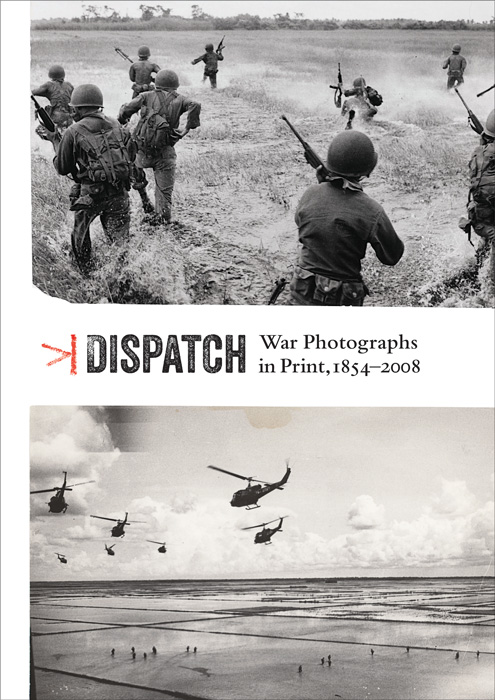

Text and image, narrative and visual representation are constantly played upon in this publication. From the onset, the cover of the book immerses the viewer – and reader – in the dichotomies involved in the juxtaposition of print photographs and their presence in illustrated magazines and press: the inside cover offers an image from LIFE magazine reproducing Robert Capa’s now iconic photographs of D Day, together with the explanatory captions, published on June 19, 1944. The materiality of the magazine is preserved – yellowed pages are visible on the edges – hinting at editorial practices that channelled both the selection and the framing of image and of text. Essays by Gervais, Kate Addleman- Frankel, and Gaëlle Morel, as well as Paul Roth’s foreword, trace the evolution of press representation of conflict, starting with nineteenth-century wars, continuing with the Vietnam war in the 1970s, and approaching present day-visual conventions and depictions of the Balkan wars in the 1990s and the ongoing wars in Afghanistan.

Gervais’s essay, “Conveying Wars in the Press: A Question of Aesthetics,” dispatches a poignant overview of war photography and how it has been employed in the press through time, influenced not only by technological changes but, more importantly, by editorial framing strategies meant to convey specific aesthetic and ideological messages to readers. The use and dissemination of war photographs, which have shaped Western visual culture, are fashioned and legitimized by specific historical contexts. Richly documented, the essay charts the transmutations of photojournalism aesthetics. Roger Fenton’s photographs of the Crimean War inspired depictions in the Illustrated London News at the end of 1855, which were further transformed by draughtsman and engravers, thus challenging the authenticity of (re)presentation. Often altered by subsequent interventions, portrayals of war in the press followed pictorial principles in order to address and appeal to their intended public’s viewing habits. In the early twentieth century there was a representational metamorphosis with the advent of news photographers, as underlined by the use of James H. “Jimmy” Hare’s photographs of the Russo-Japanese War (1904–05) in the weekly L’Illustration. Framed and arranged in order to present instead of represent conflict, as Gervais points out, photography increasingly served the purpose of seemingly offering direct access to remote zones of conflict. Rober Capa’s photographs of the Spanish Civil War (1936–39), published as photographic essays in LIFE magazine, and W. Eugene Smith’s selection of photographs of Saipan in 1944 moulded the visual depiction of war while simultaneously revealing traits of individual photographic aesthetics. These strategies influenced iconographic expectations regarding photojournalists’ visual configurations of war.

Controlling, sequencing, framing, and editing processes have been inherent to the way that war photographically reached the audience – readers of magazines, illustrated journals, and weekly publications – sometimes at odds with photographers’ intentions. Although the war in Vietnam was widely covered in the press, photographers such as James Pickerell, David Duncan, and Philip Jones Griffith took to the book format to advance their perspective. Since the 1970s, art museums and galleries have provided an alternate venue of display. Gervais’s critical account of 150 years of photographic press coverage of conflict is mirrored in the publication by the abundant presence of magazine spreads as well as original prints, underlining the changes that occurred in the “translation” from the individual image to those displayed in magazine pages.

Kate Addleman-Frankel’s essay, “Photographic Engravings During the American Civil War,” adds a significant nuance to this critical debate by focusing on photographic representations of war functioning as images meant to depict and convey a story. Although the engravings in Harper’s Weekly (1861–65) were based largely on various visual materials, photographs were employed as visual sources, mainly in terms of portraiture, as in the case of Brady’s photographs. Credits were infrequent, often missing, and, as Frankel underlines, questionable even when captions referred to the photographic source, due to technical limitations of the medium in capturing movement.

In “The Auteur Aesthetic: Subjective Expression or Documentary Restraint?,” Gaëlle Morel investigates the recontextualization of war photography with the advent of “auteur photojournalism” in the 1970s. Formal choices advanced an aesthetic based on the photographer’s recognizable and personalized gaze, as in the case of James Nachtwey’s photographs published in the news media – Time – and also exhibited in museums, art institutions, galleries, and photography books. While there has been an ongoing debate on the aestheticization of war, photographers often perform two sets of choices: on the one hand for the press, on the other hand for art institutions and personal projects. This was the case for Luc Delahaye’s coverage of the Afghanistan war in 2001, which was based on the proximity principle when published in Newsweek and Le Monde 2 – and on distance and the formal qualities of the photographic medium when exhibited at Le Maison Rouge in Paris.

Critically discussing the mutations of press photographic representations of conflict – from the Crimean War to the American Civil War, the Russo-Japanese War, the Spanish Civil War, the Vietnam War, the Balkans war of the 1990s, and the Afghanistan wars – the publication brings to the foreground the selection mechanisms that determine what is seen, how, and why. Rigorously documented and lavishly illustrated, Dispatch: War Photographs in Print, 1854–2008 is a rich theoretical and visual companion for the understanding of the dichotomies, contradictions, and complexities faced by photojournalists and the role of photographers and editors in conveying the image of distant conflicts.

Corina Ilea is associate curator at Le Mois de la Photo à Montréal, and she teaches art history at Concordia University, with a particular focus on photography, video art, and installation. She holds a PhD in art history through the Interuniversity Doctoral Program at Concordia University. Her doctoral thesis explores contemporary Romanian photography and video art produced and exhibited after 1989, concentrating on themes of containment as manifest and enforced during Communism and the long-term consequences of this socio-political system.